The Arabic class feels more like a private tutoring session, with each student receiving individual attention. Fourteen learners who are facing challenges in the subject, gather with a shared determination to improve.

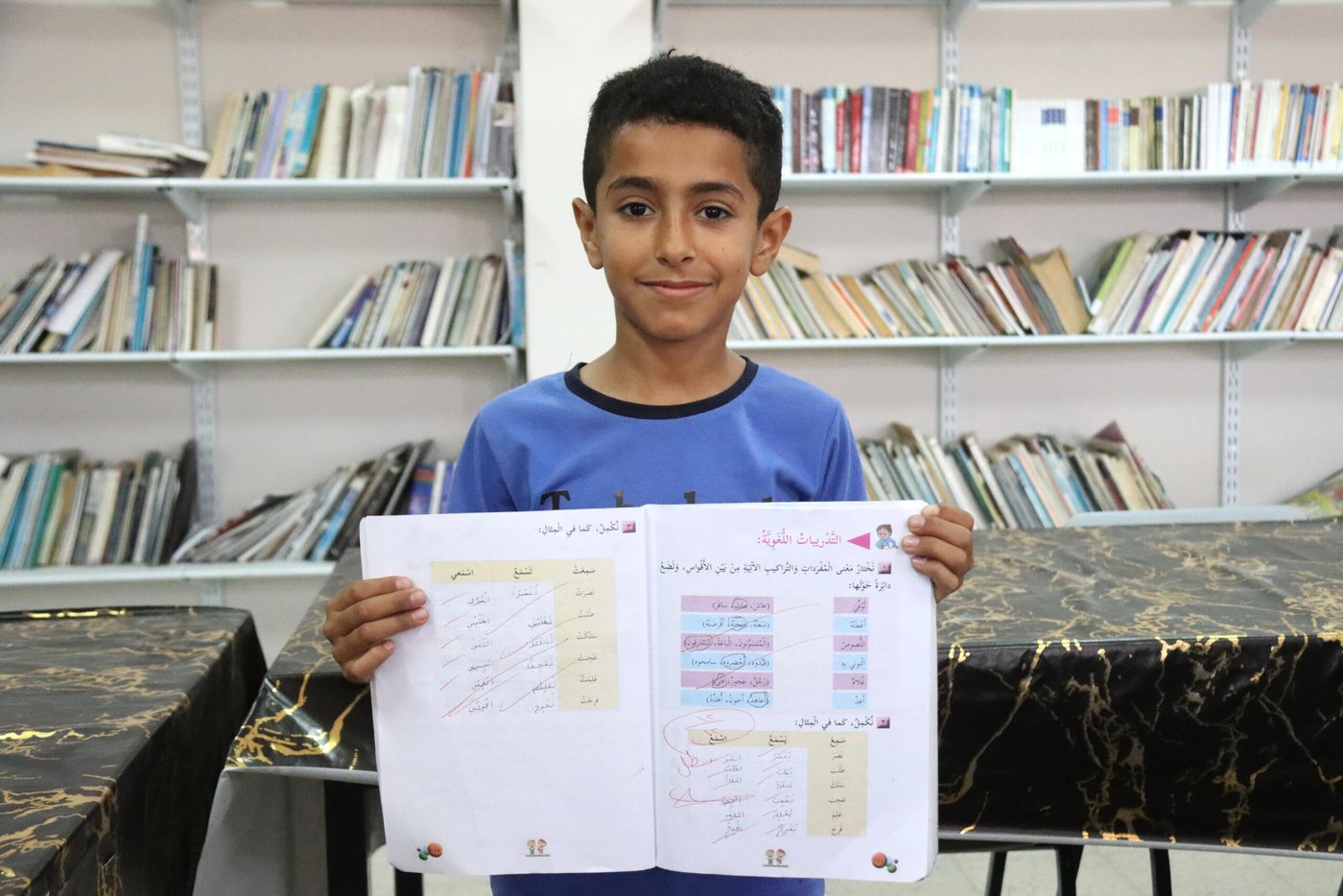

“The teaching here is fun, and I learn better. Now I know how to read and connect the letters,” says 10-year-old Ibrahim.

The maths class, taught by a different teacher, follows a similar approach. Twelve students, equally motivated, work to close their learning gaps and keep pace with their classmates.

These classes, supported by the European Union, are part of the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) remedial education programme, which helps students in the West Bank overcome learning gaps caused by disruptions in recent years. These include school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, financial crises affecting the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) Ministry of Education and rising political instability since the onset of hostilities in Gaza in October 2023.

The programme is being rolled out in 26 schools across the West Bank during the second semester of the 2024–2025 academic year, reaching 1,182 students. To lead the sessions, NRC selected and trained 54 female teachers.

At Zubeidat Boys School, one of the remedial teachers is Muyassar Zubeidat, who runs the Arabic class for students.

“I teach them the basics: the letters,” she says. The students, all of whom had grades below 65 per cent in the subject, were selected by Zubeidat and NRC’s education team to participate in the class.

“Some of my students have improved. Some have learning difficulties, and others suffer from parental neglect,” she explains, noting that she regularly coordinates with the students’ main teachers to track their progress.

What's behind learning gaps?

Midway through the conversation with teacher Muyassar Zubeidat, fourth grader Ibrahim excitedly interrupts to show off his latest Arabic exam. He had scored a perfect 12 out of 12.

He explains that he rarely gets help with his homework because his parents come home exhausted after long hours working on farms in nearby Israeli settlements. Built in violation of international law, these settlements restrict local economic opportunities and leave residents of his village with few alternatives, pushing many to rely on poorly paid settlement jobs under difficult conditions.

Zubeidat village was established in 1948, after its residents were expelled from their lands in Bir al-Sabaa (Beersheba) during the Nakba - the mass displacement of Palestinians that accompanied the creation of the State of Israel. Since then, the village has functioned as a de facto refugee community, and residents have never been allowed to return to their original homes.

In the decades that followed the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in 1967, the village has become a small, isolated enclave in the Jordan Valley. Today, the Israeli military exerts control over more than 90 per cent of the land, designated as Area C.

This has imposed a harsh economic and political reality on the village, affecting many aspects of daily life, including education.

“I started with 15 students in the remedial classes. Now there are only 14 as one dropped out of school to work,” says Zubeidat.

For some of those who remain, their day often begins at dawn, helping their parents on farms before heading to school. According to teachers, this routine affects their ability to concentrate and learn. Other factors contributing to students dropping out include parental illiteracy, lack of follow-up at home, and a general lack of motivation among students, fuelled by the harsh reality of limited future opportunities.

The impact of hostilities in Gaza

The ongoing hostilities in Gaza and their impact on the West Bank have created additional barriers to providing and accessing education. Even prior to 7 October 2023, movement between Palestinian communities in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, was difficult due to 645 Israeli-imposed movement restrictions. That number has grown to 849, further restricting the movement of the 3.3 million Palestinians living in the West Bank. According to the Zubeidat school administration, at least 14 out of 34 teachers must cross Israeli checkpoints daily to reach work.

One of them is Ibtihal Busharat, 29, who teaches maths as part of NRC’s remedial programme. To avoid checkpoints, she travels with the school principal, taking a detour that is 140km instead of the usual 40km. This means she must leave home at five in the morning. Some teachers can’t afford such a journey, and so the education process is often interrupted because many arrive several hours late due to delays at checkpoints.

“When I come through the checkpoint, sometimes I spend two hours waiting,” Busharat says. Busharat replaced another maths teacher in the remedial programme, who resigned after Israeli military operations displaced her from her home in al-Fara refugee camp. Busharat’s predecessor also found it difficult to cross the Hamra checkpoint, which separates the Jordan Valley from the rest of the West Bank.

The escalation in Gaza continues to cast a long shadow over life in the West Bank, affecting even the mental wellbeing of children. “The October 7 war had a profound impact on us. The scenes coming from Gaza affected us. They are hard to watch,” says Aseel, 13, a student enrolled in the remedial programme.

Political pressures are further disrupting education in the West Bank. The crisis is compounded by the Palestinian Authority’s ongoing financial struggles, which also affect its Ministry of Education. Israel’s continued refusal to release the PA’s monthly tax revenues means that many teachers are not receiving their full salaries. As a result, they have turned to partial online teaching to reduce travel costs. These challenges exacerbate learning gaps left by the COVID-19 pandemic, which had already caused major disruptions to education.

Restoring what was lost

“The programme gives the students confidence that they are capable of achieving and able to succeed if proper support is provided,” says Zubediat school principal Hassan Abd al-Jabbar, 58. He hopes the programme will expand to cover more subjects and be offered more frequently.

He highlights that it’s almost impossible to find private tutors to give lessons in the Jordan Valley because of its isolation from the rest of the West Bank. Therefore, he sees NRC’s remedial programme as one of the few solutions to bridge education gaps.

In addition to the remedial classes, NRC introduced its Better Learning Programme (BLP) in the Zubeidat Boys School at the start of the 2024-2025 academic year. BLP is a classroom-based psychosocial approach that creates the right conditions to improve children’s ability to learn by mobilising children’s support networks of caregivers, teachers and school counsellors. The partnership with EU Humanitarian Aid has allowed NRC to provide psychosocial support to around 250 students - including those participating in the remedial programme - helping to restore a sense of normality and hope.

“We’ve taken a holistic approach to addressing students’ needs,” said Majd Kurzum, NRC education officer in the West Bank. “By integrating the BLP into remedial classes, we not only help students catch up and recover from learning losses but also help them develop psychosocial resilience to cope with the pressures of life under occupation.”

Abd al-Jabbar says he’s trying his best to keep students engaged and not lose hope. He notes that around 12 students dropped out of school during the 2024–2025 educational year, mostly due to a lack of interest and an urgent need to work.

Despite an uncertain future, those still in the classroom are determined to stay, defying pressure to drop out and striving to catch up with their peers. They are driven by the hope that education will open doors for them down the line.

“I want to complete my education so I can help my family,” says Ibrahim.

Sign up to our newsletter to read more stories from around the world.