He opens a blue folder with the words "silent suffering" in capital letters. We meet the University of Tromsø’s Professor of Educational Psychology, Jon-Håkon Schultz, at NRC’s headquarters in Oslo.

He opens a blue folder with the words "silent suffering" in capital letters. We meet the University of Tromsø’s Professor of Educational Psychology, Jon-Håkon Schultz, at NRC’s headquarters in Oslo.

He has just returned from one of his many trips to Gaza in Palestine, where he works with NRC to help children suffering from trauma do better in school — known as the Better Learning Programme. Before returning to Norway’s northern city Tromsø, he has a few days in the capital.

In Gaza, Schultz has an office in the UN building. Three doors below his is the UN Special Organization for Palestinian Refugees’ (UN RWA) photo archive.

“This is where they digitise their collection. They have pictures of the Israeli occupation dating back 50 years.”

“I was allowed to choose the pictures I wanted from their archives,” he adds.

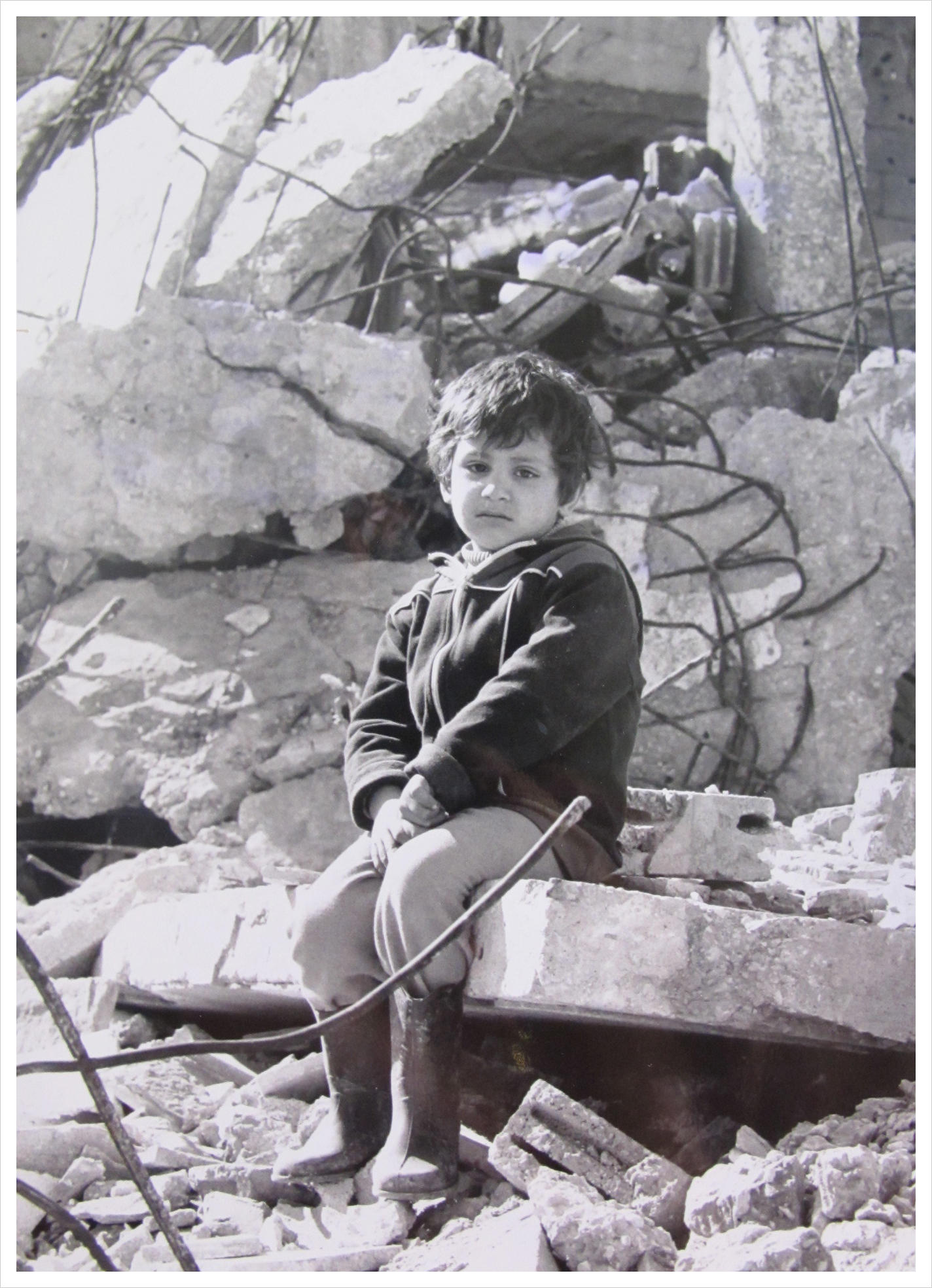

He opens the folder and spreads a pile of black and white photographs on the table: “This is from Gaza. This is the West Bank. And this – look at his expression,” says Schultz, holding a black and white photograph of a boy wearing rubber boots. He could be about four years old and he stands in the middle of a pile of rubble. The boy looks unhappy. It says on the back of the photograph that it was taken in the Palestinian refugee camp Shatila in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1982.

“What’s strange is that these are all either taken in the 1960s, 1980s or after the war in 2014, but their expressions and the backgrounds are the same,” he says as his eyes sweep over the photographs on the table.

“When people have meaning in life – like working or going to school – they have expressions of hope.”

Then there are those who have lost hope, he tells us.

“This can be challenging to understand when you live in the world's richest country.”

Without hope, nothing has meaning, explains the professor, who specialises in pedagogical psychology: “Without hope, you die.”

Helping children with trauma

Through our Better Learning Programme, NRC builds schools and helps children with trauma getting though their education. We ask Schultz if he believes that the programme gives children and young people hope.

“By giving people structure in life, you build something that helps them to survive,” Schultz says.

Without structure, he explains, they become vulnerable. “If your family can’t support you, and you struggle at school, you have nothing.”

Two good partners

Through the Better Learning programme, the University of Tromsø and NRC work together to help children who have lived through war.

Children and young people with trauma have high anxiety and stress levels. Through NRC’s programme, they learn simple coping skills, like breathing exercises, to control any overwhelming emotions. This way, they have a better chance of finishing their education.

“There is a lot of research on this,” Schultz says. “It's so simple: eight to ten deep breaths signal to the brain that what seems scary is not so dangerous after all.”

“We tell the children: YOU can do something about this.”

It’s also important that they understand that the adults in their lives can provide a shoulder to lean on in tough times. School counsellors, teachers and parents can all make a difference in the children’s lives, he notes.

But the key factor is normality.

“It's quite touching when you hear children in the group asking each other: ‘Do you also have nightmares?’”

“All of a sudden they realise that they’re not alone.”

There is a strong feeling of unity in the support group, despite only having met four times.

“They’re often in the same class or year. When they’re also in the same group, it’s easier to ask ‘How are you doing? Have you had a nightmare? Do you do the exercises?’"

Pilot in Uganda

It all started in 2006, in the city of Gulu in northern Uganda. The country had been through 20 years of civil war and was under a temporary ceasefire. Many children and young people were child soldiers.

At that time, NRC provided vocational education for young people in Uganda. Together with NRC’s staff, Schultz travelled around the country to visit our vocational training centres. Their focus was trauma, and the goal was to map the needs of the children.

“What exactly is trauma?” we ask him.

An ordinary nightmare, he explains, is like having a bad dream: waking up and feeling a bit scared. “The characteristic of a night terror is that you think you are about to die.”

Children with night terrors often dream that they’re threatened or witnessing others being threatened or killed.

“You wake up and then you're there – reliving the event that happened maybe two years ago.”

When stress hormones starts pumping around the body, it becomes difficult to go back to sleep.

Trauma exists everywhere. But according to Schultz, we view trauma differently depending on where in the world we live. In Uganda, Schultz asked questions like most people would in the west: Are the children traumatised? Do they show symptoms of trauma?

“The response we received was: ‘No, everyone’s okay,” he recalls.

But when they asked how they could help, they received a very different answer: “They told us: ‘Well, it would be nice if you can get the students to pay more attention in school,’” Schultz says.

Many of the young Ugandan students couldn’t sleep at night and would fall asleep during class. Schultz explains that the teachers often responded with beatings and strict discipline. But they eventually saw that the harsh treatment wasn’t working. These children were usually top-motivated students. The only obstacle was that they slept in class.

Schuiltz and his team decided to get to the bottom of why the children fell asleep.

"We stayed for quite some time to do interviews, and found that many students were former child soldiers,” he says.

At that time, what these children had gone through was probably the most grotesque act carried out against children globally, he believes.

And at such a large scale. It’s estimated that there were nearly 20,000 child soldiers in Uganda.

“They told us that they couldn’t sleep at night.”

Schultz tells us that while teachers wanted the children to concentrate and stay awake during class, the students wanted help with the root cause: their night terrors.

To solve the situation, Schultz and his team used evidence-based methods that had previously yielded good results. But these methods were mainly used in western settings, with one-on-one sessions. This was impossible to carry out in Uganda, mainly because of limited resources and magnitude of the issue.

“We had to adapt the methods by focusing on groups and training staff at the school.”

“We asked: ‘How much can we take away from the complexity of the treatment and still continue?’ We had to try our way forward. For us researchers, this was quite extraordinary.”

Schultz raises his arms enthusiastically and continues: “It worked very well in Uganda.”

Expanding to Gaza

In 2012, NRC and Schultz started their work in Gaza. It didn’t take long before they saw positive results.

NRC’s Better Learning Programme is now up and running in 130 state schools and 250 schools run by the UN.

The children they help usually have five nights of night terrors every week. On the bright side, he says, they usually occur in the morning – the last stage of the sleeping cycle.

But the children are still sleep deprived and find it difficult to concentrate in class.

“I mean, we’ve all been there. You miss two hours of sleep one night and you’re in a whirl all day.”

He laughs and continues: "But this usually occurs over a long time.”

On average, the children have night terrors for over three years, he explains.

Over 70 per cent of the students have not told their teacher about their night terrors. Even parents are often unaware of what their children are going through. Still, most of them know that their children are having trouble sleeping.

The breathing exercises have proved successful: almost 70 per cent of the children now rarely have night terrors or even better, they’re completely gone.

Schultz tells us that they also train parents, teachers and school psychologists.

“When they come back to us and say, ‘Now I've tried this on my wife’, you realise that it works and that they believe in the methods.”

He stops to think and asks: “Speaking of Gaza, those who read this interview are people who support NRC’s work, right?”

Schultz is concerned about how Israel’s occupation of Gaza has troubled the population for ten years.

“In times of war, the situation receives attention. But we often forget the crisis that is taking place in between the wars.”

“For too many children, that’s when the crisis is happening.”

Although the war in Gaza was declared over in 2014, many children relive it every time they have a nightmare or night terror. “For these children, the war is not over,” he says.

But not everyone can be helped

“Why?” we ask him.

Schultz believes that some children keep having night terrors because they’re going through continuing distress, like abuse or violence.

“Nevertheless, we’ve reached phenomenal results,” he says.

His main goal is to achieve what he calls lasting change. If he can prove that the exercises show long-lasting results by a minimum of six months after the sessions, they’ve made significant change to a young person’s life.

"We recently checked results ten months after treatment and found and that they last,” he says.

Helping children across the world

Today, the Better Learning Programme assists children in several countries — from schools in the West Bank to refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Myanmar.

The programme has also evolved into a research project: Schultz collaborates with researchers from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in the US and Australia as well as the University of Philadelphia.

“How has the collaboration between the humanitarian and the academic world been so far?” we ask.

“It has worked very well between the two very different organisations with the same goal.”

NRC’s staff members act immediately when an event occurs, he says. “That's not how we operate. I think we complete each other.”