“I remember when I was a small boy and this place had many trees. It was a vibrant community, full of happy people. But the trees have been gradually cut down, for charcoal and for home construction. Our people used to plant onions, potatoes, corn, barley, wheat, water melon and garlic. However, these activities have been abandoned, due to the water scarcity and many more people have moved away to Jijiga town, to look for jobs,” he explains.

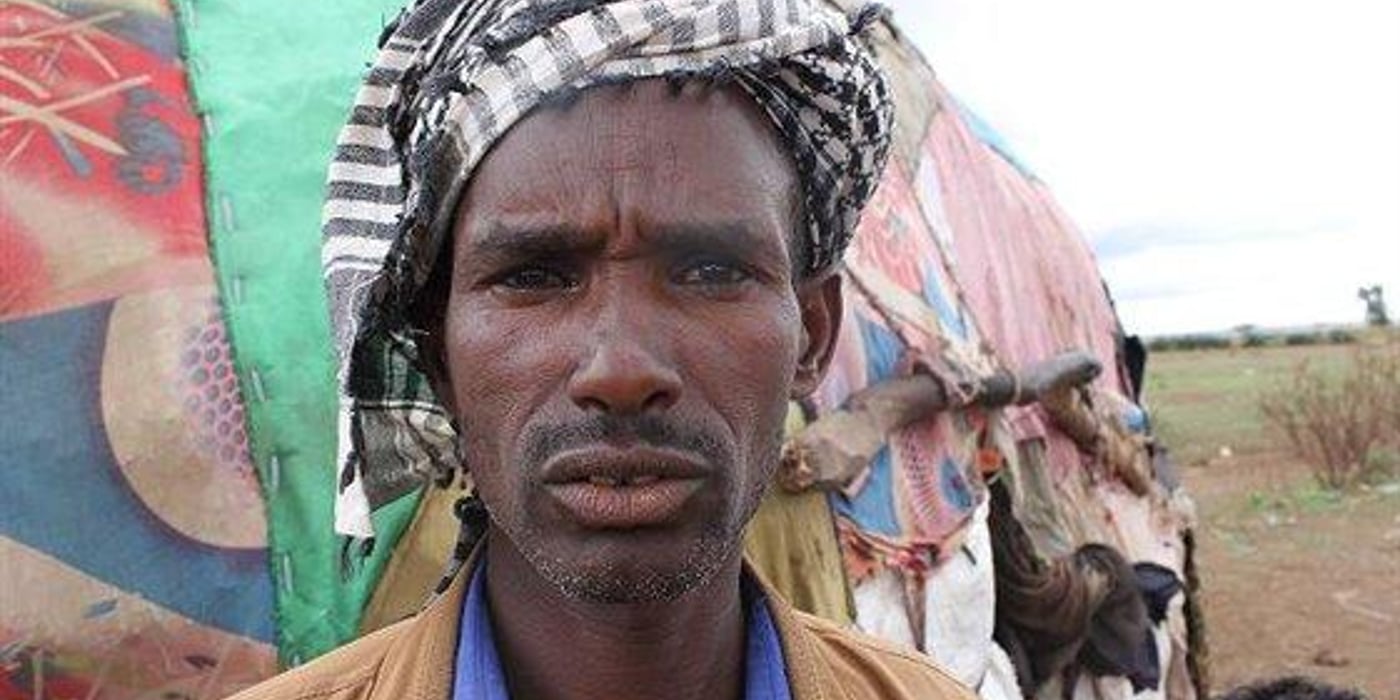

Abdi Ahmed Ismail was born in Barisle Kebele of Kabrebiyah Woreda, in the Somali region of Ethiopia, and has nine children. He explains, almost breaking down into tears that, as a result of this catastrophe, many people have moved to Dagahabur to escape the harsh conditions in Barisle. The ongoing drought in the Somali region of Ethiopia has had the worst effect on his livelihood situation. Only one cow has survived the drought.

“Because of the climatic shocks, over the past 20 years, our people now lack the physical tools and mental strength to keep carrying out land cultivation and planting crops. If my grand-father was to wake up today, he would not recognize this place. It has become a shell from what it used to be. In those days, our families were wealthy, there was an abundance of milk, meat and ghee. The grass would reach waist-height, so if you were sitting down, the person passing nearby would not see you,” he recalls.

During his youth, they used to play ‘hide and seek’ in the long grass. There were water ponds at every 50 to 100 metres.. Abdi says: ”We took the water for granted, it was everywhere, almost at our doorstep.”

With the changed conditions, water ponds have vanished, the few shallow water reservoirs, cannot hold water for long periods, and the communities can only rely on government water trucking.

“My grandchildren will inherit a very hostile environment if nothing can be done to reverse the cycles of the drought. They will inherit land that is barren, harsh and unkind to human survival. You cannot play hide-and-seek when your throat is crying for water and there is no grass to keep you in hiding,” he says.

Optimism amidst destitution

According to Abdi, something can be done to build resilience within the community and face the future. Provision of farming tools, seeds and other forms of recovery options can be provided by humanitarian agencies.

“Farmland development can be a good starting point, as savings will help us repopulate our livestock. Unfortunately, most of the oxen were swept away and we only have hand cultivation as the remaining option,” he explains.

On water conservation, he sees a good option in building more shallow water reservoirs, as well as drilling boreholes in the area to tap the ground water for domestic consumption and for irrigation. While the government has constructed three shallow water reservoirs, only one of them is functioning. The other two need to be cleaned and strengthened to hold water efficiently.

NRC started responding to the El Nino impacted drought emergency, in the Siti zone of Somali region, with 64 emergency latrines and seven water point construction and rehabilitation interventions. Additionally, we completed four rainwater harvesting schemes, in Babile District of the Fafan zone, that catch surface-moving rainwater and sustain over 2,000 households for about three months. We have also rehabilitated a borehole in the same district, benefiting over 5,000 individuals.