Nyakuan Dador, originally from Mangatein, has been displaced in Juba since the civil war started nearly three years ago. The conflict officially broke out on 15 December in 2013, between forces loyal to President Salva Kiir and those loyal to former Vice President Riek Machar.

Hunger on the rise

Since then, an estimated 1.6 million people have been displaced inside the new country's borders. In addition, more than 640,000 people have fled to neighbouring countries. Hunger is on the rise.

According to UNOCHA, more than 6.1 million South Sudanese are in need of protection and humanitarian assistance such as food, clean water, education and other basic services.

Nyakuan Dador's story:

Nyakuan is a mother of six children. When the civil war started three years ago, Nyakuan and her children were forced to flee their home. They came to the UN Protection of Civilians (PoC) site in Juba.

Nyakuan’s husband regularly leaves the camp to work as a trader in different villages.

“It is really hard to sustain our big family with so little income,” says Nyakuan. She runs a small restaurant at the PoC.

Lacks food and education

Nyakuan says they lack good education, healthcare and food in the camp.

“Life was very different before the war,” she remembers.

“We used to have money to pay school fees and hospital bills.”

Now, they are totally dependent on the assistance of humanitarian organisations. “These organisations are our parents now,” she says.

Her only message to the international community is that it must provide support for education.

“If our children go to school every day, they will become something good in the future,” she believes.

Nyamandong Isaac Rial's story:

Nyamandong came to the UN Protection of Civilians (PoC) site right after the conflict started in South Sudan. Before she escaped, she was in her hometown of Malakal together with her parents, three brothers and four sisters. Then her family decided to move to move to Juba to seek protection, but her father stayed behind.

“Since then, we don’t know anything about our father,” says Nyamandong.

“We cannot communicate with him and we don’t know if he is still alive or not.”

“We can go nowhere”

Nyamandong says she is tired of being displaced.

“I don’t see any future here and I just hope peace will come soon,” she explains.

She still remembers when she was 16 years old in Malakal, where she used to enjoy going out with her friends. Now, she says there is not much she can do.

“We can go nowhere.”

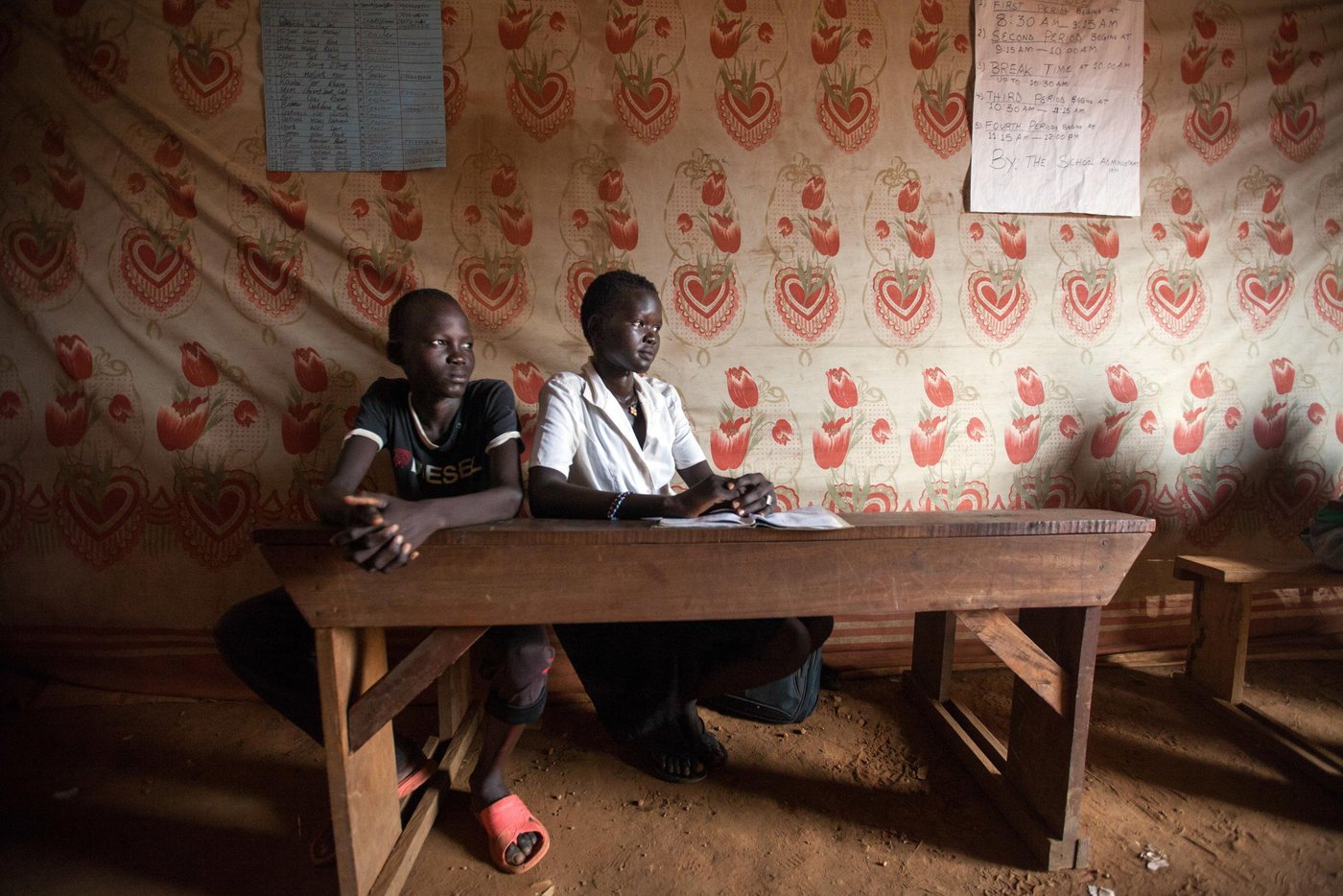

According to Nyamandong, who dreams of becoming South Sudan’s minister of education, schooling is not very good in the camp.

“In our school, we don’t have books or pencils,” she says.

In addition, access to healthcare is limited among the displaced.

“We really need more assistance,” she says.

Christmas in the camp

This Christmas is the third in a row that Nyamandong and her family celebrate outside their home.

“Nothing is the same here, we cannot buy clothes for the young children or cook food for guests,” says Nyamandong.

She is most concerned about the children.

“They do not understand why we cannot celebrate Christmas properly,” she says.

Gatluak Kang’s story:

For three years, Gatluak has lived alone at the UN Protection of Civilians (PoC) site in Juba. He has four wives and seven children, but they live as refugees in Gambella in neighbouring Ethiopia.

Gatluak used to be a wealthy farmer in his hometown of Maiwut. When South Sudan became independent in 2011, he was a soldier. Right after the civil war broke out in December 2013, he sent his wives and seven children to a refugee camp in Gambella, while he himself sought protection in Juba.

Gatluak spends his time working voluntarily as a security guard in one of the schools of the camp.

“It’s my only way to support the community at my age,” he says. His shelter is right next to the school and he patrols the facility at night to make sure nobody breaks in and steals the furniture.

Optimistic

Gatluak is optimistic about the future of South Sudan.

“Sooner or later, I am sure we will have our freedom and peace,” he says.

He urges the international community to help finding a political solution.

“I really need to join my family before I die,” he says.