At just nine years old, Halima lived a simple but steady life. She attended school, played with her friends after class, and helped her mother with household chores. Her parents farmed and relied on small daily earnings to provide food for their ten children. Life was not easy, but it was familiar and it worked for them.

Then El Niño arrived.

The rains were relentless. Day after day, water poured down. What began as concern quickly turned into fear as the floodwaters crept closer to homes, and farms. One night, the water entered the village, rising faster than families could respond.

“I remember my parents shouting for us to wake up,” Halima recalls. “The water was everywhere.”

Within hours, our village was submerged. Homes collapsed, crops were destroyed, and livestock were swept away.

Halima’s family had no choice but to flee. They gathered the younger children and escaped, leaving behind their house, their belongings, and Halima’s schoolbooks.

Displacement and survival

The journey to safety was long and exhausting. Like many flood-affected families, Halima’s parents walked for hours under the hot sun, guiding their children through muddy paths and flooded terrain until they reached Kismayo town. Eventually, they settled in Luglow displacement camp, on the outskirts of the city.

For Halima’s family of ten, life became a daily struggle. Food was scarce, water was limited, and income opportunities were almost nonexistent. Her parents focused entirely on survival, finding food, collecting water, and securing the basic assistance available in the camp.

After arriving at the displacement camp, education slipped out of the family’s priorities as everything in their lives changed. Halima’s parents were overwhelmed by uncertainty, their days consumed by the struggle to secure food, water, and basic survival for their children.

Months passed, and Halima remained at home while other children walked to nearby schools. Each morning, she watched them pass by, holding their schoolbags tightly.

“I stayed home while neighbouring kids went to school,” she says. “I used to watch them pass by with their schoolbags. For a long time, I thought education was not meant for displaced girls like me.”

Her days were filled with household responsibilities including fetching water, helping her mother cook, and caring for younger siblings. Slowly, the idea of returning to school began to fade.

A second chance to learn

Hope returned in early 2024, when Halima’s mother heard about a registration opportunity for displaced children through an emergency education programme supported by the Education Cannot Wait (ECW) – the United Nations global fund for education in emergencies and implemented by the Norwegian Refugee Council along with SOS and WARDI.

“At first, I hesitated,” her mother recalls. “I didn’t know if she would be accepted or if we could manage it.” But the thought of Halima losing her education forever was too painful to ignore. She registered her daughter.

When Halima was accepted at Luglow Primary School, her excitement was overwhelming. For the first time since the floods, she felt seen and included.

“Today I am at school, and I am very excited about this,” Halima says. “I thought education was gone forever for me.”

Rebuilding learning

Through ECW, 657 displaced children (310 girls and 347 boys) were supported to access education in Kismayo. At Luglow Primary School, support went beyond enrolment.

Teachers received monthly incentives to teach displaced children. A waterline was connected to the school to improve hygiene and safety. New chairs replaced broken benches. Girls received dignity kits, ensuring they could attend school confidently. Recreational materials helped restore joy, play, and psychosocial wellbeing.

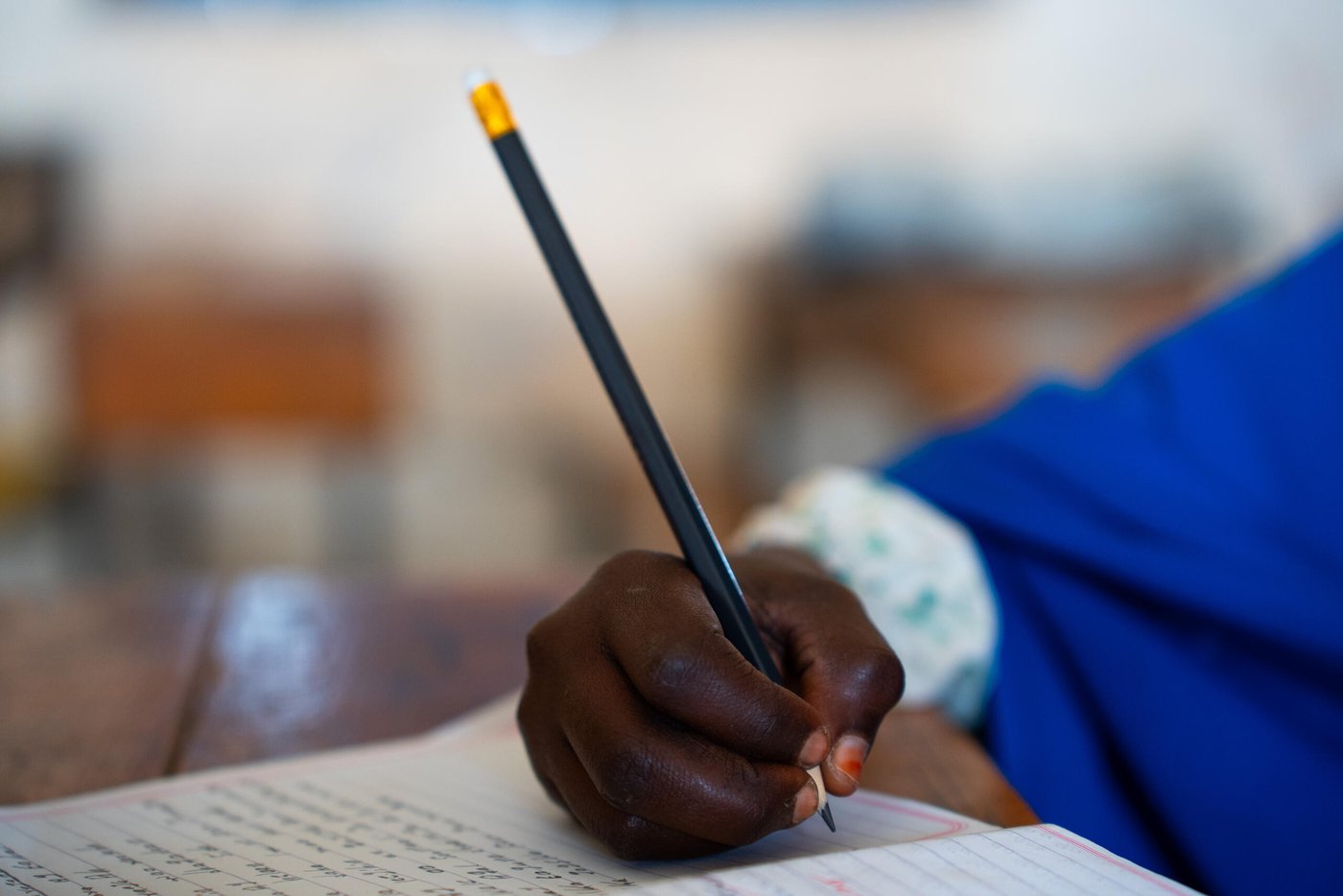

For Halima, these changes transformed her daily life. “When I sit in class now, I feel happy,” she says. “I like reading and writing. I like being with my friends again.”

Her teachers noticed the change quickly. “At first, Halima was very quiet,” one teacher explains. “Now she raises her hand, participates, and helps other students. She has confidence again.”

Dreams beyond displacement

The education project officially ended in August 2025, but Halima’s journey did not. Learning continues at Luglow Primary School, now run by the Ministry of Education of Jubaland State, with support from other education partners to ensure continuity.

For Halima, school is no longer just a place to learn, it is a place of hope after loss. “I dream of becoming a doctor,” she says proudly. “I want to help people when they are sick, like the people who helped us.”

Her family remains displaced, and life in Luglow camp is still uncertain. Yet education has given Halima something no flood could wash away: belief in her future.

“She talks about school all the time,” her mother says with a smile. “Even when we struggle, I know her future will be different.”

Thousands of children have been displaced by climate-related disasters across Somalia. Floods, droughts, and conflict continue to disrupt education, pushing children - especially girls - out of school.

Halima’s journey shows what is possible when education is prioritised during emergencies. “I thought school was not for girls like me,” she says. “Now, I know I can learn. I know I can be something.”

In the classroom at Luglow Primary School, Halima writes carefully in her book, determined not to fall behind again. The floodwaters may have taken her home, but they did not take her future.

Somalia is one of the world’s most neglected displacement crises. It may not make the headlines, but the needs are urgent. Share this story and help shine a light on the world's neglected displacement crises. Your voice matters when others remain silent.