There are many things that can give a clue as to what has happened in different parts of Syria during the decade-long crisis. One of them is a Syrian’s eyes.

When you mention the name of a town or a village to a Syrian, their eyes will tell a story without the need for words. If you mention “Aqraba”, a small town in rural Damascus, a Syrian’s pupils will dilate. Like a screen, their eyes will reflect pictures of violence, destruction and blood, blinking back the tears while remembering beloved faces and places.

However, on this particular day Syrian eyes were shining. Aqraba was the venue for a special celebration to mark the last day of the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) programme targeting out-of-school children and those who are at risk of dropping out.

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world, including Syria. Support our work today

In the past, Syrian parents would cherish that bittersweet moment where they waved goodbye to their children as they headed off to school. However, the conflict has changed all that. The typical morning scene, when a child prepares for the school day ahead, now features very different conversations, thoughts, emotions and even characters.

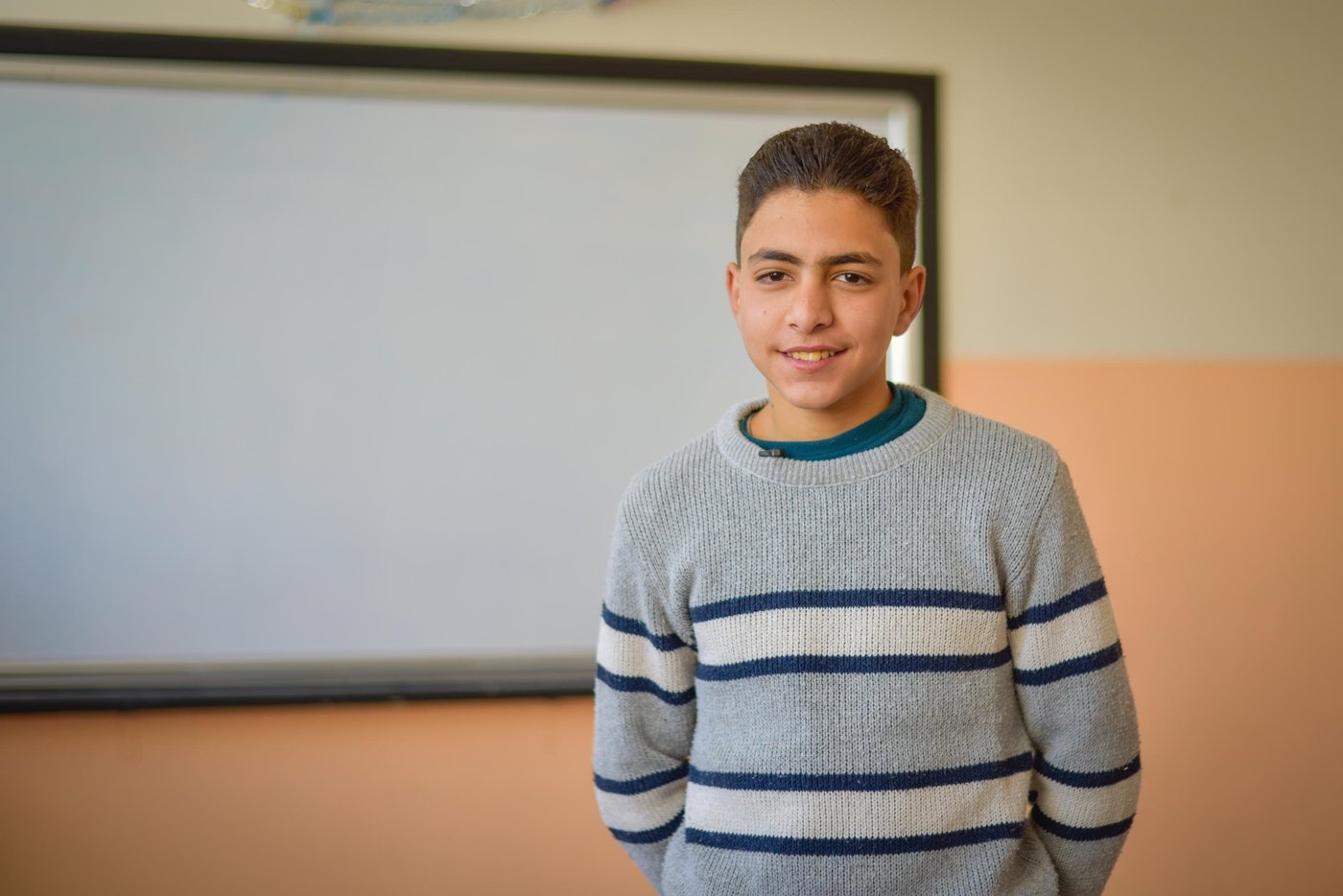

Mohammad, 14, from Aqraba, dropped out of school a year and a half ago due to behavioural problems, a common issue for teenagers who have experienced the unstable living conditions of a prolonged crisis.

His mother Ola tells how one morning they found themselves fleeing their home town. “Our decision to leave Aqraba was a sudden one. It was 4 am, dark, and the noise was deafening. Only when I was far away from the darkness and the horrific sounds did I realise that I hadn’t taken any clothes for myself.”

Some 6.2 million Syrians, including 2.5 million children, have had similar experiences. More people have been forced to flee within their own country in Syria than anywhere else in the world.

Feeling like a stranger

Ola and her family were displaced for six months. The mother of four did not feel comfortable, even though the community where they were staying was supportive and welcoming.

“A feeling that I was a stranger haunted me, no matter what I did,” she says. If the mother felt that way, as someone who is capable of recognising and processing her feelings, one can only imagine how her children must have felt.

“We were the last to leave Aqraba and the first to return,” Ola says with pride. But when they returned, they found their home was destroyed, like so many other buildings in Aqraba.

“As a temporary solution, we rented an apartment,” she explains, “and in parallel, we started rehabilitating our home little by little. But due to the soaring prices we had to stop all construction work six months ago.”

Education is a priority for Ola’s children

Her children’s education was and still is a priority that Ola is not willing to compromise on. Even before they had to leave Aqraba, she encouraged her kids to go to school – especially her daughter, as she knows how valuable education can be for a woman.

She remembers the times she spent pacing in circles worrying about her children’s safety – hearing the war raging around her, feeling helpless, and having no means of communication to check on them while they were in school.

“One day, the clashes were so loud, and my daughter was frantically scared, I hugged her to calm her down then I started to cry with her,” Ola recalls. “Then I helped her to stand up and told her: if you want to be a well-regarded intellectual woman in the Syrian community, you must go to school.”

Teachers are also suffering

Syrian teachers are also suffering. Before entering the classroom, a teacher must leave everything behind and focus on the children, with their schoolbooks on their desks and their futures ahead of them. Yet how can someone forget that their salary is barely enough to get them through the first week of each month?

Like the rest of the Syrian community, teachers are suffering from drastic economic hardships. A basic food package to feed a family for a month – bread, rice, lentils, oil and sugar – now costs at least 120,000 Syrian pounds (equivalent to €39), which far exceeds the average household salary.

“The despair has grown bigger inside of us. Like every other Syrian, teachers are heavily affected by the current living conditions. The living expenses versus the income, the electricity shortages and many other factors – they all pile up and affect teachers’ professional and personal lives.” Says Ola.

Child labour

Ola thinks that her son Mohammad could have avoided dropping out of school if he had received more care and attention from the school itself. She explains: “I think that children his age need to be encouraged, as they do not know what’s best for them. When they receive sufficient attention from their school, they will be motivated to grow a deeper attachment to education.”

She tried her best to encourage Mohammad in his education but was unable to manage it alone. As a result, he dropped out of school. Dropping out of school increases the risk of child labour, and indeed this was the case for Mohammad, who began to work in a relative’s workshop tiling floors. While his friends were preparing for school, he was heading out to work.

“I worked from 7 am to 6 pm,” he recalls. “My main task was to stand beside my employer and help him with any task he might require, like cutting the tiles and kneading the cement.” Mohammed worked to support his father, who owns a small mechanic workshop, and to help to cover his family’s expenses.

A more welcoming school

With the support of EU Humanitarian Aid (ECHO), NRC implemented a programme called “Creating a Welcoming School” in one of Aqraba’s schools. This involved rehabilitating the school building and providing teacher training. Teachers were introduced to new techniques designed to make the teaching process more productive and less stressful for themselves and the students alike.

Later on, the school hosted another NRC programme targeting out-of-school children. As an Aqraba resident, Ola noticed the positive impact that NRC’s intervention had on the local community’s approach to education.

“After NRC started its programmes in Aqraba last summer, more students were motivated to go to school,” she says. “I was so happy and relieved when I walked into the school, knowing that my child was going to a place where high levels of care were given to all aspects of the education process.”

Rehabilitating Aqraba

In recent years, violence has provoked large waves of emigration as Syrians risked their lives to seek asylum in other countries. Today, even though the violence has noticeably declined, Ola’s children still speak about emigrating, even her youngest who is in kindergarten.

However, Ola loves Aqraba and does not want to leave. She says: “I want to be remembered as someone who stayed and brought life back to this area. The local community has already helped a lot in rebuilding Aqraba but there is still much that needs to be done.”

No-one can provide solutions in the near future for Syrians like Ola and her family. As ever, they are reliant on their coping mechanisms and willpower, which have been brutally tested over the last decade. Life does not stop, hardships continue to pile up, and it’s getting harder each day for Syrians to hang on to hope.

“I wish that all of us would love this town,” says Ola. She believes that the love which pushes a person to take positive action is the key to a brighter future. After a decade of conflict, it is time to listen to Ola and other Syrians. They must be the number one source and motivation when taking action.