A decade into the Syria conflict, millions of children have been born in displacement inside Syria and across the wider region. Hundreds of thousands of young people have had their lives shattered and uprooted from the safety they grew up in. Lebanon alone hosts an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees, around half of whom are under the age of 18.

As the situation in Lebanon worsens as a result of compounding crises, children are spending more time at home and are more likely to drop out of education. Schools have now been closed for over a year as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. The unprecedented economic crisis has driven many families into extreme poverty.

For the most vulnerable families in Lebanon, it is very challenging to engage children in remote learning activities. Many households lack the necessary internet connection or equipment; others feel forced to send their children to work to make ends meet.

According to a report by the Lebanon Humanitarian INGO Forum, more than half of Syrian school-aged refugee children, among them children with disabilities, are currently out of school, with 10 per cent accessing non-formal education. And a 2020 UN report on Syrian refugees in Lebanon revealed that 89 per cent of young women and 57 per cent of young men between the ages of 19 and 24 are not in education, training or work.

Children and young people from Syria told us what it means to have been a refugee in Lebanon for a decade with no change in sight.

These are their stories.

***

Moemen: “We didn’t ask for a war”

Moemen is a 17-year-old Palestinian boy who fled his home in Syria almost ten years ago to find safety in southern Lebanon. The war had reached his family’s door and the security situation deteriorated drastically.

“The sound of bullets and shelling became a part of our everyday life,” says Moemen. “My uncle was killed and the only way for us to be safe was to flee.”

“It was difficult to adapt to life here in Lebanon when we first arrived. I had a hard time finding friends, and people looked down on me for being a refugee. But eventually with time things started to change.”

“I started playing football and was good at it, so I became more and more accepted in our new community. It created a sense of belonging. Football is my passion. It makes me feel good and keeps me going.”

Being a refugee is tough because we are always dependent on aid to make ends meetMoemen, 17

“Being a refugee is tough because we are always dependent on aid to make ends meet. Before the coronavirus crisis, jobs were already scarce, but today the economic situation is even worse. My dad’s salary was cut by half and we are barely able to cover our rent and electricity costs. It is especially difficult for us Palestinians because no matter how long we live here or what we accomplish, we will always be seen as refugees.”

Moemen’s first encounter with the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) was two years ago when his family was supported with 12 months of rent-free housing through NRC’s shelter programme. Today, he is enrolled in an NRC computer skills course, funded by Germany through the German Development Bank, KfW.

“I am happy I got the opportunity to participate in the computer class. Everything today requires computer skills, and when we finish this course, I will get a certificate which will be helpful in my future job search,” he explains.

Moemen dreams of a future where he can practice medicine. “I want to become a doctor, but I know that as a Palestinian in Lebanon, I will not be able to do that. Palestinian refugees are prevented from working in certain professions and medicine is one of them.”

“My wish for the future is that people around the world think about us refugees. We didn’t ask for a war, it just happened to us, but we too are humans with feelings and needs,” says Moemen. “I hope for a brighter future, where I will get the chance to travel to another country and pursue my dream of becoming a doctor.”

***

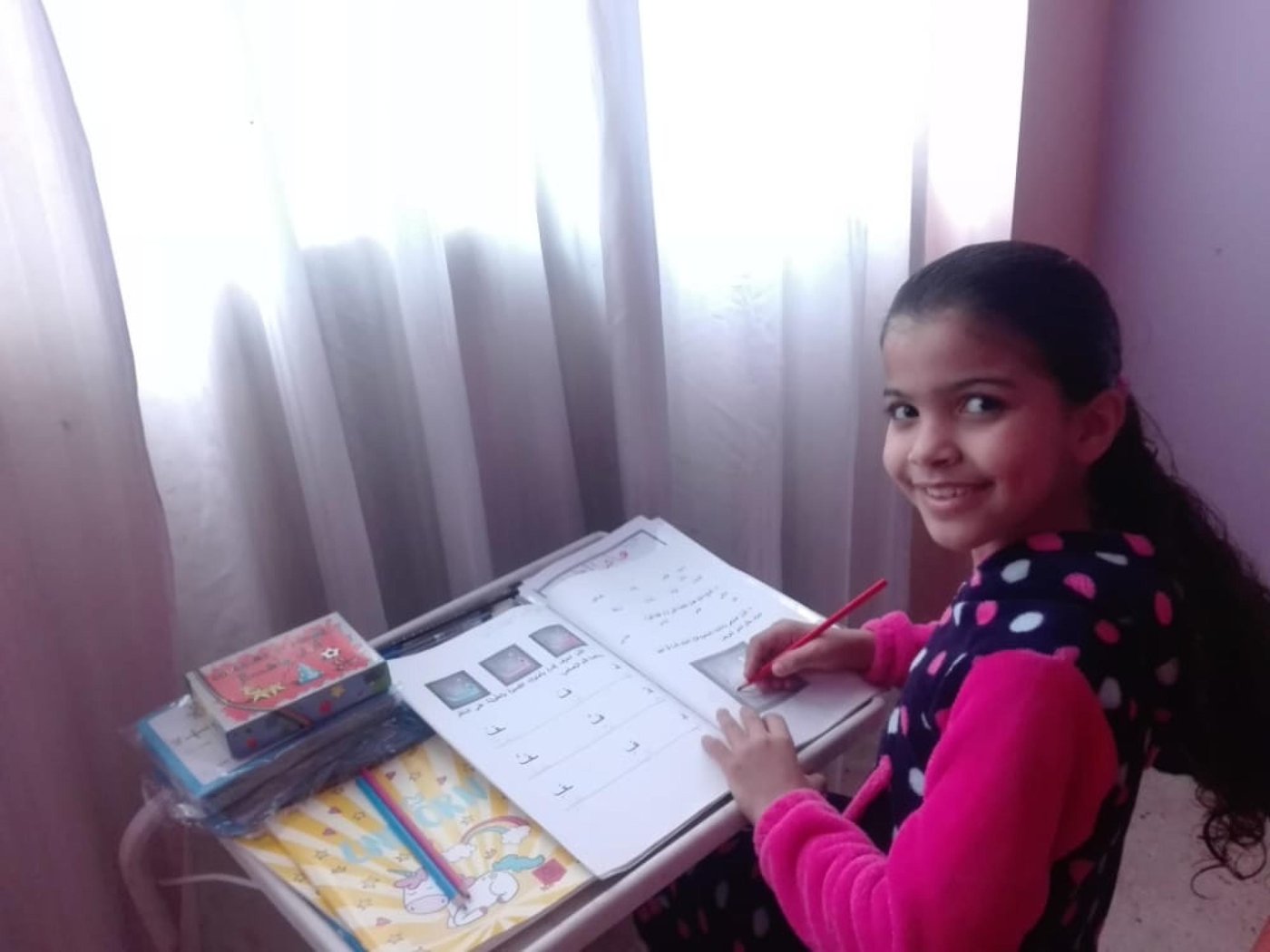

Hajar: “I love my teacher and my classroom”

Hajar was born in Lebanon after her parents fled from Syria in 2012. Although, she has never visited her homeland, her Syrian roots colour her everyday life in the northern city of Tripoli.

When her parents fled their hometown almost ten years ago, little did they know that would be the last time they saw their home.

“We fled Syria thinking it would only be a matter of months before we could return. But today, almost ten years have passed and we are still refugees,” says Noura, Hajar’s mother. “I even took the keys of our house with me but unfortunately there is no door left to open. Our house was completely destroyed in the war.”

Hajar, like any other girl her age, likes to play, draw and enjoy her neighbourhood, but being a refugee has made life difficult for her and her family. The deteriorating economic situation, protests and Covid-19 weigh heavily on them. “The coronavirus affected my children’s mental health. They are always indoors because we worry about getting the virus. They don’t meet anyone and haven’t played with their friends outside on the street for a long time,” says Noura.

Hajar is enrolled in NRC’s Basic Literacy and Numeracy (BLN) programme, but was only able to attend classes at the education centre for a few months before the pandemic hit Lebanon. “I love my teacher and my classroom. We used to draw and hang our drawings on the wall,” says Hajar. “I like to spend most of my time studying and drawing, I draw my mum, my dad and the entire family.”

NRC provided school supplies and internet subscription cards so that Hajar and her siblings could take part in remote learning. “Education is very important because we must learn how to read and write,” she says with enthusiasm. “After each class, I tell my parents what I have learned. I prefer going to school to studying at home, because I can spend time with my friends and play with them during the breaks. Now I am constantly bored.”

Before the pandemic, Noura only used to help her children once they returned from school, but now, she is playing the role of the teacher, which exhausts her and takes up most of her time.

“Although we don’t have to pay for travel anymore, which was challenging for us, I still believe it would be better if my children were in school to learn directly from the teacher,” says Noura. “I wish life could go back to normal so that my children’s wellbeing would improve. Children need to be out playing with other kids.”

***

Mohammad: “I would have graduated by now”

“If the war had never happened, I would have graduated by now. I would be working as a teacher and own my own house and land,” says 27-year-old Mohammad, a Syrian refugee living in Arsal with his wife and two-year-old son.

Mohammad was a first-year university student when he was forced to flee his hometown, Qusayr, in 2013. “The war took a toll on me. The shelling and fighting prevented me from attending my classes and I had to drop out of university,” he says.

“During one of the strikes my leg was injured and I had to flee to another city to get medical treatment. But when the war reached that town, I was forced to flee to Lebanon. As if that wasn’t enough, our house and farm were destroyed so we lost them too.”

The war in Syria meant losing a lot of things that were precious to Mohammad. He was especially shaken by the news that one of his cousins had died, someone he loved dearly and considered to be his best friend. “Losing my cousin was terrible. We used to work together at my father’s home goods shop, where my cousin was in charge of maintenance,” says Mohammad. “I miss him and our farm a lot. We used to spend hours and hours playing in the green fields with the trees and water.”

Life in Lebanon is different to what Mohammad was used to, but he is grateful to have found safety.

“I consider myself lucky because I am safe, and here in Lebanon I got the best opportunity a refugee like me can wish for: to enrol in a skills course,” he says. “I came across an ad from NRC on Facebook about an aircon and refrigerator maintenance course and applied directly. I know my cousin would have been so proud of me because this was his profession, so for me it is a tribute to him.”

“It is a practical course so of course the online sessions were difficult, but we had a great teacher who took us through every step thoroughly. I gained a lot of skills and experience that I am sure will help me when I apply for a job in the future. I advise anyone who can get an opportunity like this to take it. This is what can help them get a job in the future.”

***

Khalil and Mahmoud: “It is sad to see Syrian youth who are illiterate”

Khalil is a ten-year-old Syrian boy who lives in one of the informal tented settlements in Lebanon’s Bekaa valley. His family fled their hometown in 2011 after the clashes in Syria escalated around them. Although Khalil doesn’t remember the war, the thought of it frightens him. "I don't know anything about the war. My parents tell me about when they fled Syria and I feel scared when someone mentions it,” he says.

“We ran for our lives to seek safety for our children. Khalil was only a baby when we fled,” says Mahmoud, Khalil’s father. “The war changed all our lives. We went from living in a beautiful house that belonged to us, to living in a tent on mud rented from a landlord who discriminates against us. We are ten individuals living in the same tent. That’s our life today.”

“What breaks my heart the most is the fact that a whole generation have lost their educational opportunities. It is sad to see Syrian youth who are illiterate. If the war had never happened, they would have built their future by getting an education. If it wasn’t for NRC, my children wouldn’t have been enrolled in school and wouldn’t have learnt how to read and write.”

Khalil loved going to his classes, but since the coronavirus pandemic he has only been able to study through NRC’s remote learning programme. “The best part of my day is when I start studying with my siblings. It feels good to learn how to write and read,” says Khalil. “The thing I like most about school is reading, but I prefer going to school to studying online because I don’t have my own phone to follow classes.”

“It’s difficult to be a refugee because we are always seen as strangers in Lebanon no matter how long we have lived here,” says Mahmoud. “I have a disability and can’t work so we are constantly struggling to make ends meet. The financial situation in Lebanon has made the situation even worse. My only wish is that my children can continue their education and that we will eventually be able to return to live in peace in our home in Syria.”

To mark the ten-year commemoration of the Syria conflict, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) published a regional report: The Darkest Decade: What displaced Syrians face if the world continues to fail them. It sets out the future of the Syria displacement crisis within Syria and in the wider region. The report looks at future drivers and conditions of displacement for Syrians across the next decade, and outlines the actions needed to avert another decade of crisis.

In Lebanon, NRC’s Basic Literacy and Numeracy programme, remote learning courses and skills training courses for youth, among others, are funded by Germany through the German Development Bank, KfW.