“I have lost a lot of things,” he says, “but when I enter the classroom, I leave all that behind me. I teach like I would normally, and I am free.”

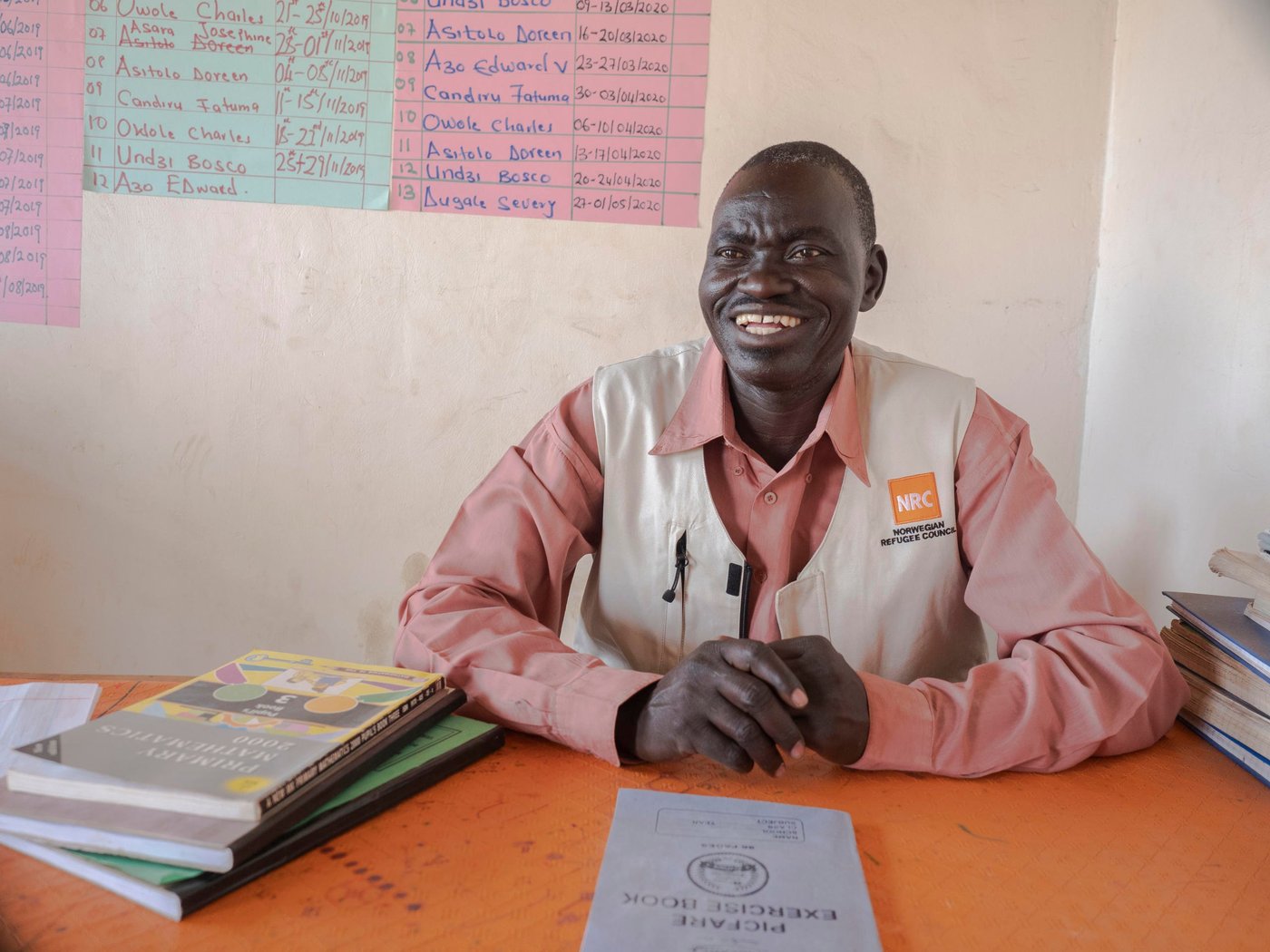

Dugale Severy is 38 years old. He began his teaching career in his hometown in South Sudan straight after leaving university. Throughout his own schooling he benefitted from teachers who made things clear, and this gave him the courage to learn more. Teaching, he says, is his way of serving others.

“I love teaching,” Dugale says with a smile. “When you are a teacher, you can help everybody without borders. I want to inspire my students to become teachers themselves so that they can help other refugee children.”

Dugale now teaches on the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Accelerated Education Programme in Nyumanzi Settlement, Uganda. Many of his students have lost loved ones and missed out on many years of school. All have been forced to flee their homes.

This is something Dugale understands, as he too was forced to flee.

A sanctuary among the chaos of conflict

In 2011, South Sudan gained independence from Sudan, bringing an end to Africa’s longest civil war. Two years later, violent conflict broke out, shattering the newly acquired peace. The conflict has since forced over four million people to flee their homes.

Dugale found a sanctuary amongst the chaos through his work. “I instantly enjoyed teaching. It was a good escape from the war. There was no interference.”

Despite the peace within the classroom walls, it was often hard to ignore the threats that surrounded them.

You have to stop teaching and figure out how to respond. Whether you need to run.Dugale

“During the war, we weren’t able to teach at our best because of fear. Sometimes you are in class and you hear the sound of guns. And then you must stop teaching and figure out how to respond. Whether you need to run.”

As the violence got closer to home, Dugale decided he must flee with his family to keep them safe.

Education offers a route out of poverty

Dugale and his family crossed the border into Uganda in 2016 with only their ID documents, clothes, and enough food to last two days. “This is all I came with. The rest of the things I left in South Sudan,” Dugale says with regret.

He finds it difficult when he thinks about everything he has left behind. “My property has been looted and some of my relatives have been killed, so it is difficult to think about.”

Despite Uganda’s open border policy for refugees, life without work can be tough. Many families benefit from food aid from organisations like NRC, but this doesn’t reach everyone. As a result, many refugee children drop out of school to take on adult responsibilities.

But Dugale believes that education provides a route out of poverty. NRC’s Accelerated Education Programme is taught at primary level and welcomes students up to the age of 18. Some of these young people are scared of re-entering education, Dugale says: “They see their age and they see their size they think they cannot fit.” But he believes that it is never too late to learn.

“For those who do join the programme, they can instantly see a way out of extreme poverty,” he continues. “They really know something. When they are in the classroom, they can see their future ahead and that their future is bright.”

Squeezing seven years into three

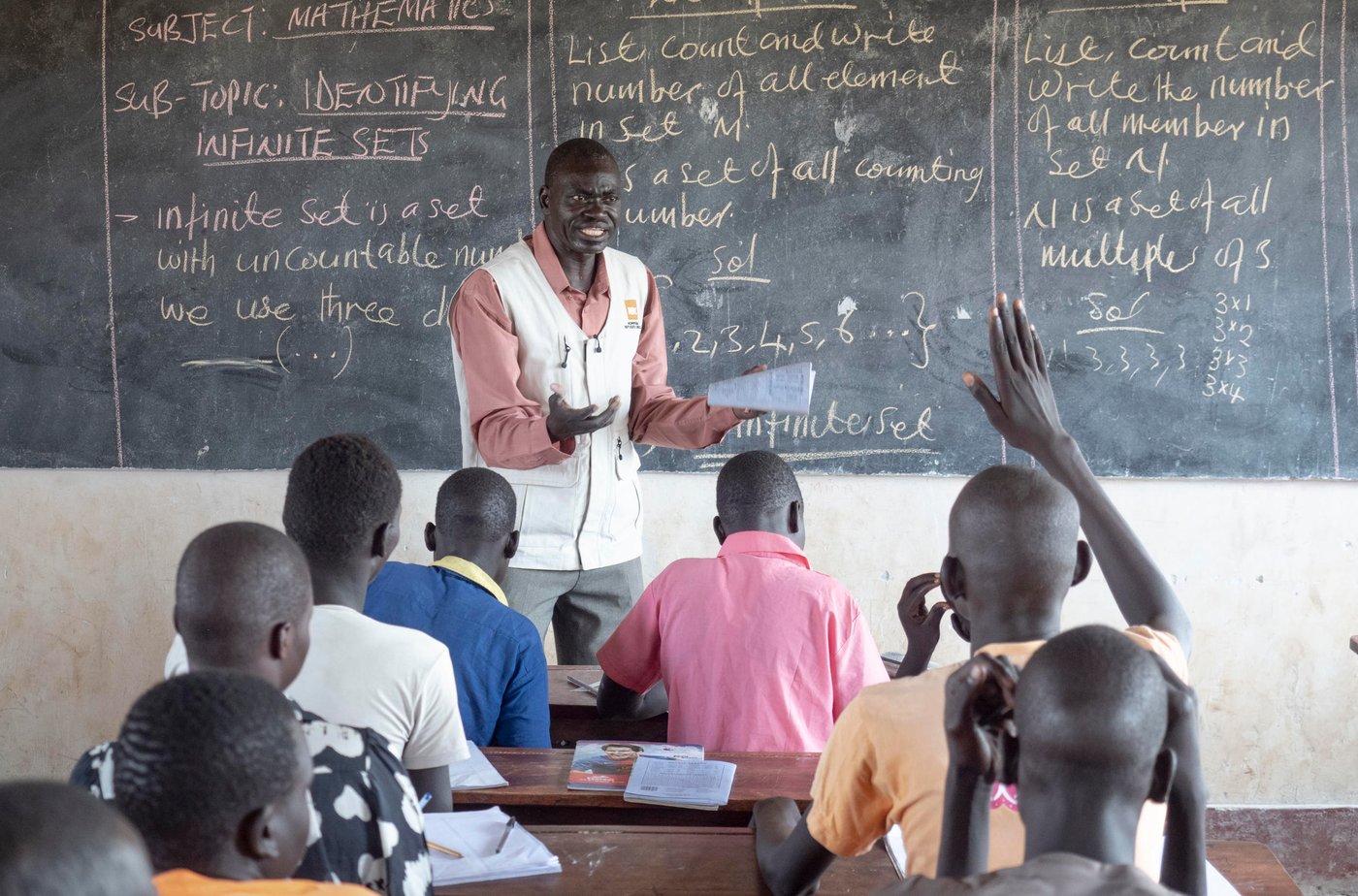

Dugale’s job is a challenging one. He must squeeze seven years of schooling into just three. The students in his class are from different ethnic groups, and they all have unique stories to tell about where they come from. “You know, a lot of my students have lost family members,” he explains.

A lot of students demonstrate challenging behaviour when they begin the programme. Dugale describes one student who stood out in his memory.

“Back then, he was drinking alcohol, he was smoking. His behaviour was really very bad. But throughout the programme something changed within him. He is now in secondary school, and he is so bright. I stay in touch with him, I will never forget him because of his progress and the way his attitude changed.”

Dugale continues with pride: “He is doing so well, and I know he will never, ever, go back to the life that he had before.”

A calm environment

Dugale knows that despite his students’ challenging pasts, each one has something unique to offer. His energy and enthusiasm are infectious, and his students benefit from this in the classroom.

“Sometimes they are happy,” he says”. “But their lives have been difficult. There is a time for everything. If there is also some joy, we hold onto it and enjoy it. I am always talking with my students, whatever situation they are in. We provide a calm environment.”

“Singing is one of the methods we use in the classroom. You know, when you sing, it can make my students feel upbeat. You make a bit of fun, and the students will be laughing. When I do this, especially when teaching something that is challenging to understand, I know that the lesson can go successfully.”

“I see that what I am doing here is good”

Education is one of the most underfunded of humanitarian responses. According to Education Cannot Wait, only two percent of humanitarian funding is allocated to education. This should not be the case. The benefits of education run far deeper than addressing the immediate needs of individuals or communities.

Dugale believes that education is the key to creating peace in times of conflict: “Teachers are the commanders who can fight this war. There must be teachers who can educate the next generation. When you have knowledge, you can give it to the rest of the world.”

Teachers like Dugale are essential to ensuring that young refugees can rebuild their futures. He knows that he alone cannot stop the devastating cycle of war, poverty and displacement. But with every new student that joins the Accelerated Education Programme, there is hope for the future. And that impact will continue for generations to come.

“The students in my class are active. There is hope. When I am teaching and they are getting something from me, I see that these are the people who are going to uplift the economy, even uplift the world!”