Since the outbreak of Covid-19, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) has been working around the clock to ensure that refugee children and youth can exercise their right to quality education.

Mohammad, 13, is one of these children. He is originally from Hama in Syria but fled to Lebanon together with his family six years ago. Now he lives with his parents, three sisters and three brothers in a small apartment outside Tripoli, North Lebanon.

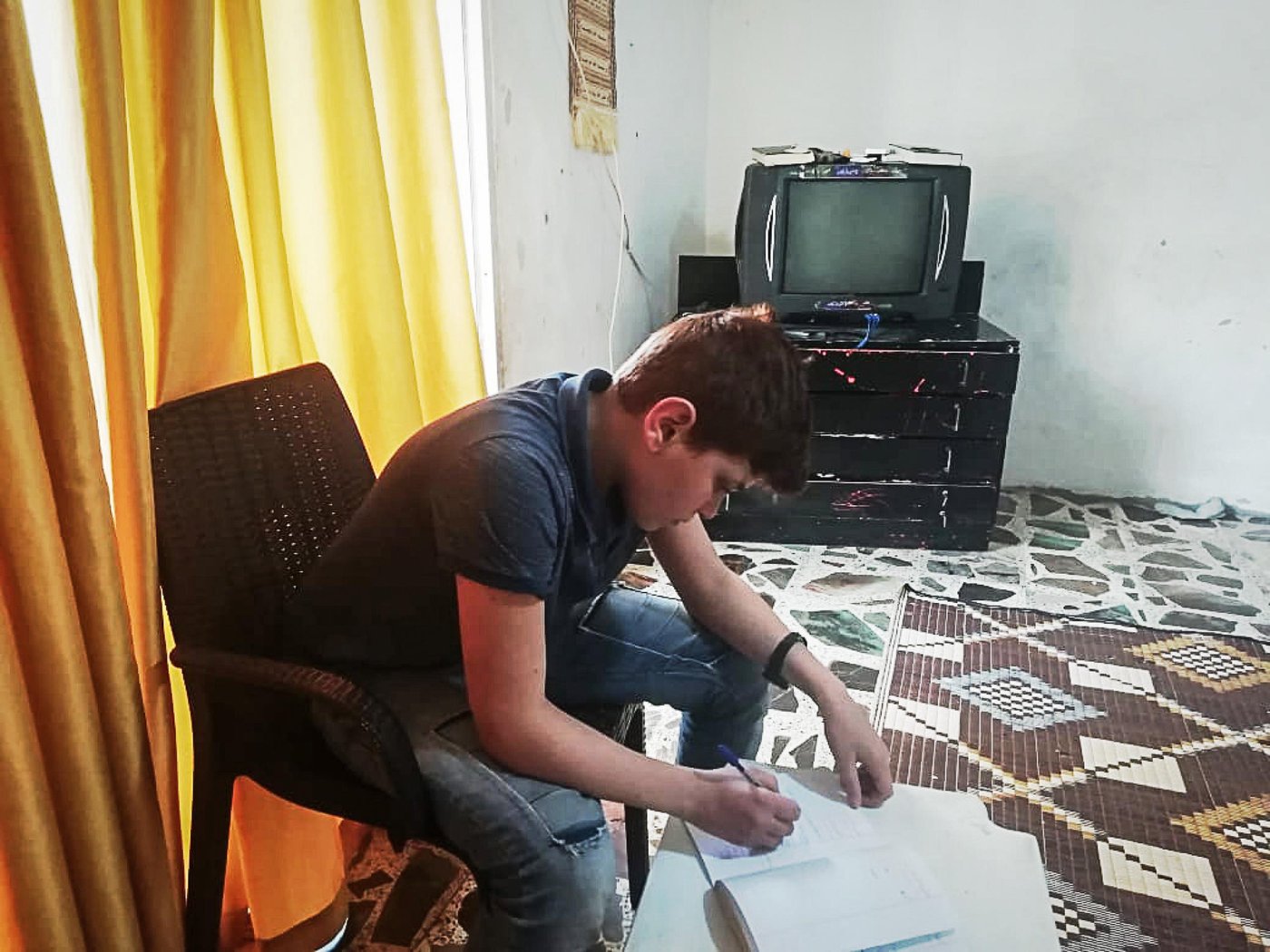

Due to the coronavirus crisis and school closures, NRC staff are no longer able to have direct contact with children and their parents. It is Mohammad's mother, Fatima, who sent us the photos, and NRC staff in Lebanon who spoke to Mohammad and his mother on the phone.

“Although it has been six years since we arrived here, I still wish we could go back every single day. We could play football as much as we wanted in front of our home and we had a huge yard where no-one bothered us,” says Mohammad. “In Lebanon we can never finish a football game. The neighbours always get annoyed and ask us to go back home.”

Nine years into the Syria crisis

Nine years into the Syria crisis, Lebanon remains a country with one of the largest concentration of refugees per capita in the world, hosting an estimated 900,000 Syrians. Together with around 29,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria in addition to approximately 500,000 Palestinians already present or born in Lebanon since 1948, this relatively small country has been under considerable economic and social pressure.

Despite the substantial progress made through government and donors’ commitments, major barriers to education continue to keep Syrian children from enrolling in learning.

UN data for the 2018-19 school year estimates that 58 per cent of children aged 3-18 (331,020) are out of school. Of these, 36 per cent (138,459) of compulsory school-aged children (aged 6-14) are out of school – defined as not in any form of government-recognised formal or non-formal education.

Refugee children are bearing the brunt

The coronavirus crisis has led to closed schools and disrupted the education of millions of learners in Lebanon. Children and young people in displacement have often already missed out on years of education due to war and conflict previously. Without assistance, school closures due to Covid-19 will make them fall behind even further.

When education activities stopped due to the Covid-19 outbreak, Mohammad and his brothers were very upset. Going to the NRC learning centre, meeting their friends and learning were part of their daily routines. “It’s not easy to stay at home. I feel down, but there is nothing we can do,” says Mohammad with hesitation.

Remote teaching

“To meet the needs of Mohammad and 1,200 other children enrolled at NRC learning centres in Lebanon we are now implementing remote learning using communication platforms such as WhatsApp, combined with follow-up phone calls to provide guidance and support,” says Rayan El Baf, one of NRC’s child protection technical officers in north Lebanon.

“The remote learning has benefited my children a lot,” says Fatima, Mohammad’s mother. “Instead of leaving them behind during this period, the remote learning methods show us that NRC continues to care about the education of our children and appreciate their efforts to learn. It helps them connect with their inner selves and gives them courage and strength to know their own worth.”

With support from European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), NRC is also providing Mohammad with remote psychosocial support under the Better Learning Programme (BLP) to help him cope with stress during these challenging times.

“I love practising the breathing and balance exercises. Although it is a bit difficult, the different techniques help me calm down and reduce my stress,” says Mohammad. “Also, the life skills session about setting goals has pushed me to keep practising football and not give up on my dream to become a professional football player,” he adds.

Stay and deliver

“Although our learning centres were closed due to the Covid-19 situation, we never stopped delivering educational messages to the children,” explains Rayan El Baf. “We regularly contacted them and their parents over the phone to check on their wellbeing, raise awareness of the situation and share learning materials.”

Since the lockdown, Mohammad spends most of his time at home. He either focuses on the NRC learning materials, revises the lessons, or plays with his siblings. He also sometimes helps his father at work, who sells coffee on the streets for a living.

“The remote teaching allows my children to revise and remember the information they received in the classes,” explains Fatima. “It brings some variety to the daily routine during the coronavirus lockdown. This not only helps them to learn but also to feel more positive about the situation.”

New ways and solutions

“Though adopting remote learning, we have been able to develop a positive bond between us, and the parents are becoming more involved in their children’s education. We are always trying to find new ways and solutions to deal with any challenges that might arise. However, the hardest challenge is perhaps that we cannot answer the children when they ask us when they can come back to our centres to see us and their friends,” Rayan concludes.

“The learning centre was a place where I felt safe. I miss both my friends and the teachers. But most of all I would like to return to Syria,” Mohammad says.