She wraps her thin shawl tighter around her small body. Two bare feet protrude from under her simple cotton dress. The home she describes consists only of a simple plastic tarpaulin for a roof, some blankets for walls and a plastic mat to covers the earth floor. This is how she has lived half of her short life.

Families who have sought refuge in big cities are often called “the forgotten refugees”. More than half of the world’s displaced people live in urban areas, where they hope for protection and where it is easier to find paid work. In Afghanistan, more than 1.2 million displaced people live in such settlements.

Lost her father

“For millions of displaced children and adults in Afghanistan and other countries, having a safe place to call home is not a matter of course. And this year, they are also fighting against the coronavirus, which has led to reduced incomes and sky-high food prices, among other things,” explains Astrid Sletten, who leads the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) work in Afghanistan.

Join Astrid Sletten at work in one of the world’s most dangerous countries

Amina knows all too well what it means not to have a proper home. When her father was killed by a grenade that struck their garden four years ago, her mother Gulla, 45, and the five children fled to one of the poor suburbs of the capital city Kabul.

The children are starving

“This will be our fourth winter here,” says Gulla. “The children are starving. We barely survive on what my two sons earn.”

She continues: “Every morning, they go out into the streets to collect plastic and scrap metal to sell. They earn between USD 1 and 1.50 a day, which is just enough for us to have two meals a day. Sometimes, they come home with potatoes or vegetables given to them by people at the market. Sometimes they even come home smiling with boiled rice and meat. I can’t remember the last time we had a proper lunch.”

I try to comfort my children and tell them that this is only temporary, that things will get better.Gulla, 45, mother of five

Read more about what it means for displaced families to have their own home

The family has to fetch water from a water station in the neighbourhood. They have no way of heating the water.

“When my sons come home in the evening, they are dirty and stink of rubbish, but all they have to wash themselves is a bucket of cold water,” says Gulla.

No school

None of the children in the family go to school. Gulla explains: “The money my sons earn is barely enough for food, and I can’t afford to send any of my children to school.”

The family has a single light bulb as their only light source. It is connected to the neighbour’s power supply and Gulla pays for the use. When it rains, the water seeps into the tent, and the cold and snow make it impossible to keep warm. The winter in Afghanistan can be as cold as Scandinavia.

“I try to comfort my children and tell them that this is only temporary, that things will get better,” says Gulla.

Help that saves lives

“Last year, we received several reports that children had died of hypothermia or pneumonia,” says Astrid Sletten. “Now our colleagues are fighting a battle against the clock to help as many families as possible get a proper roof over their heads before the full force of winter is upon them.”

“Gulla and her children have been dreading another cold winter in the tent, but are among the families who are now receiving help,” she continues, and explains that she and her colleagues will be helping 1,500 of the most vulnerable families in Kabul with shelter and warm winter clothes.

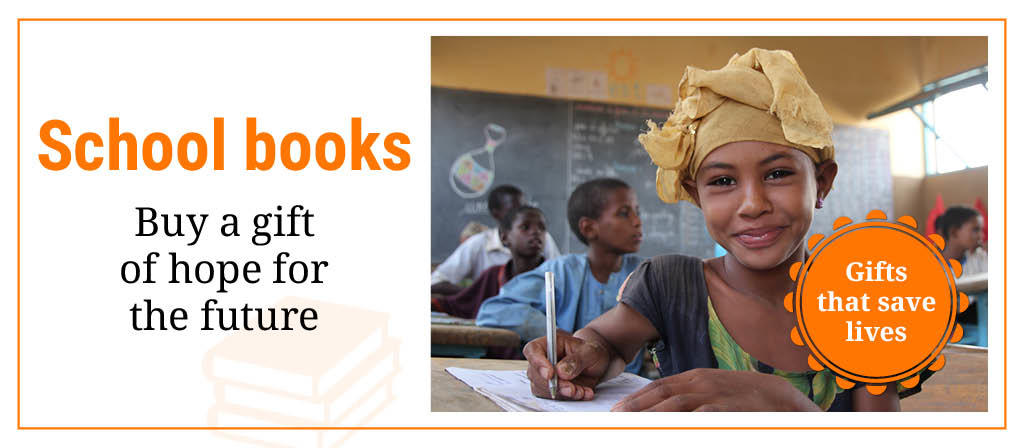

Read how our “gifts that save lives” make a difference

Last year, we made sure that more than 77,000 displaced people in Afghanistan received help to get a roof over their heads.

Read how we helped Ana and her family get a new home last winter