“I was in so much pain and went to a hospital in Mosul, but they refused to allow me in.”

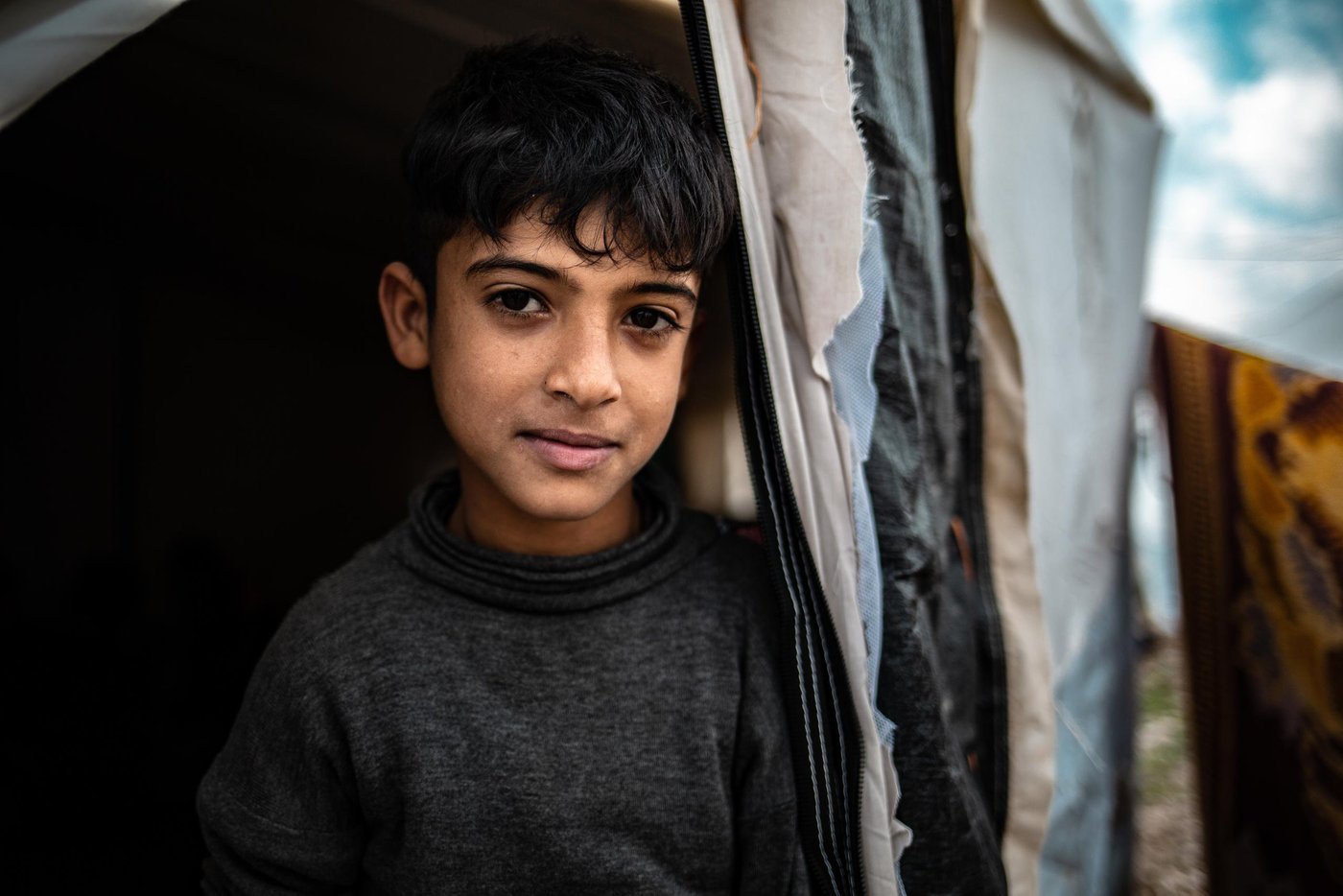

More than one year since the end of the war in Iraq, thousands of people are still missing their documentation, deprived from their most basic rights as citizens and facing complete exclusion from their society.

Read also: 45,000 children may become stateless in post-IS Iraq.

No documents, no healthcare

“I went to another hospital, hoping they might understand my situation, but they wouldn’t help me unless I brought my ID.” Eman is married, but she is unable to prove her identity or that she is married because her husband is missing. He went missing back in 2017, during the military operations to retake Mosul from the Islamic State group (IS). Eman hasn’t heard from him since she fled.

The hospital staff questioned her about her husband and whether her pregnancy was a result of an affair. “They threatened to keep my child in the hospital until the father showed up, if I insisted on giving birth there.” For Eman, this was unacceptable. She went home and delivered her child without medical assistance, with no doctor to help her.

Her daughter never received a birth certificate. Now she is almost two years old and has not even been vaccinated yet. The child suffers from bronchitis and kidney stones but receives no medical care.

When Eman heard about a hospital in Hamam Al-Alil camp, in Mosul governorate, where they provide medical assistance to undocumented people, she tried to go, but was stopped at the checkpoint. She did not have the required ID documents to pass.

Children don’t receive vaccination

In the city of Hawija, located in the central part of the country in Kirkuk governorate, children without birth certificates are not receiving vaccinations, according to Salah, a medical assistant at the directorate of health.

The undocumented families cannot go to hospitals to receive the vaccinations need for their children. They count on campaigns led by individual efforts from some local clinics and NGOs for their children to get vaccinated. “Lack of vaccination caused the emergence of new types of diseases such as Measles, which did not exist before IS.”

Those who don’t have birth certificates they are more exposed to diseases. “The emergence of these diseases stared with the children born under the IS group period, as most of them have no birth certificates.”

Across Iraq, an estimated 8 per cent of displaced Iraqis outside of camps and 10 per cent of Iraqi families residing in camps are missing at least one form of civil ID.

According to a new study conducted by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and our partners, the financial cost of issuing, updating or renewing documentation is the most significant barrier to accessing documentation. This leads many to not even attempt to renew or update their documentation. Another barrier is overcrowded civil directorates and lack of understanding of the process.

Not allowed to leave the camp

Hana, a mother of seven children, lives in a camp for displaced people in Kirkuk governorate, in central Iraq. When their hometown in Mosul was under the control of IS group, the entire documentation issuing process stopped. Three of her children are undocumented. This is causing immense problems for the family, especially.

Hana’s two-year-old suffers from asthma. “He got sick after fleeing to the camp. The tents can be very cold during winter. My child needs healthcare and I cannot even take him to a hospital close to the camp.”

The authorities don’t allow anyone leave the camp without civil documents.

“Under IS’ control, there was no system to issue official documents such as birth certificates. We only had the vaccine card for new born babies,” Hana explains.

Undocumented people living outside the camps also lack access to assistance from government and sometimes from humanitarian organisations too.

Risk being removed from school

At the school in Hamam Al-Alil camp in Mosul, headmaster Ibrahim confirms that children need ID to register in schools.

There are high numbers of undocumented children in the camp. Ibrahim allows all the children to attend classes, also those who don’t have an ID, but says they risk being thrown out of the school by authorities at any time.

“Because they don’t have the needed documents, my children are unable to attend school. They lost their future and their dreams,” says Nada, a divorced woman and a mother of seven children living in the camp. Like many people, she’s not able to pay for transportation and fees for issuing new documents.

NRC estimates that about 45,000 children in camps across Iraq alone are missing birth certificates or other civil documentation, putting them at high risk of being sentenced to a life on the margins of Iraqi society.

Hana shares Nada’s concern for the future of her children. “I believe my children will not have a future without education. It’s the only way for my children to reach their dreams, but now this dream is taken from them too.”