THE MALDIVES: “They are really brave, right?” the taxi driver says with pride. In Paris, in Brussels, in Tunis, if you mention ISIS jihadists to Muslims they are all mortified. Almost apologetically, they say: “They are out of their mind.” But in the Maldives the response is: “They are heroes.”

Many Western tourists don’t even realise this is a Muslim country. But the Maldives, although a non-Arab country, boasts the world’s highest number of foreign fighters per capita: around two hundred out of its 400,000 citizens. The government denies it. But nearly every Maldivian has a brother, a cousin or a friend in Syria. While the world watched the Olympics in August 2016, in the Maldives they watched the battle for Aleppo. Cheering on al-Qaeda.

A paradise of thousand islands

For us, the Maldives is a chain of 1,192 islands. But for Maldivians, there is only one true island: its capital, Male. On the island, there are just a few shops. A school. A soccer field. Sometimes there is no electricity. But for whatever you need, you come to Male. It looks like countless other cities; but it barely stretches two square miles to house its 130,000 registered residents. Its actual population is probably more than double that. In Male, every inch is inhabited.

In one of the main streets, Buruzu Magu, I squeeze into a gap that offers a glimpse of a picturesque landscape – a trio of houses, blue, green and yellow. In the background, a spiral staircase. Behind the door on the right there are five people; behind the left door, nine people. Behind the middle one is a group of migrants from Bangladesh. It’s just one room and they are 18. They take turns sleeping.

In the neighbouring building, behind a plywood plank that serves as a door, a mother and daughter chat in the dark. To their right, on a shabby mattress, an old woman wheezes, her grey hair resembling filaments of a blown out light bulb.

There are 16 people here altogether. They wear rags and worn out shoes. The walls are patched up with jute and metal sheets. The kitchen is a camp stove. There are no tables, chairs, windows. Body odour pervades throughout. But then a strange sight: on the wall hangs a plasma TV, received in exchange for votes during the last election.

An average salary here is 8,000 rufiyah, approximately USD 510. For a shack like this, rent costs around 20,000 rufiyah per month, and electricity can run up to 7,000 rufiyah.

A capital in hell

Kinaan grew up in a house of this kind. Six people in a room, his parents bickering constantly. Their shower was the sea. Today he is 31 years old, and he is the most feared name of Male’s underworld.

About 30 gangs rule Male, each of them with up to 500 affiliates. If we take the highest estimate, that’s one tenth of the residents and one fifth of youth. In the first and only report on street violence, published in 2009 by the Human Rights Commission of the Maldives (HRCM), 43 per cent of those surveyed said they don’t even feel safe at home.

Kinaan was jailed for the first time at the age of 15, for participating in a brawl. He’s been convicted twice, but he never served a sentence. “We are on the payroll of politicians,” he explains. Sometimes politicians pay convicts more than USD 1,000 to smash a window or attack a journalist. This frees offenders from further incarceration.

So what does he do for a living? Kinaan laughs: “I am serving a 25-year sentence.” A heroin addict and alcoholic since the age of 17, he earns a living as a drug dealer. Alcohol here is prohibited, but residents can find heroin cheaper than vodka.

Kinaan has been trying to change his life for ten years, but to no avail. He can’t get a job. “You are stigmatised forever,” he says. And so now he’s decided to offer himself a second chance – he’s going to Syria.

“It’s easy. Nobody stops you,” he explains. Because these criminals know the government’s shady dealings first hand, Kinaan says, they’re happy to see them go.

For Kinaan, any place is better than Male: “In Syria, at least, I would be killed for a good reason.”

Death penalty and Sharia law

For many young men here, Syria is an economic and moral opportunity. It’s a sort of redemption. Kinaan only changed his mind to try to save his brother Humam from execution.

After a 60-year suspension, the death penalty is in force again. Humam is on top of the list, charged with killing a deputy. He is 22 years old. He has retracted his confession, denounced undue police pressure, and, according to Amnesty International, has often showed signs of mental disorders.

Besides reintroducing the death penalty, the new criminal code has also formalised Sharia law for the first time. But here, Islam has always been a part of politics.

When Maumoon Aboul Gayoom, who held a thirty-year tenure as president from 1978 to 2008, assumed power, the Maldives was mostly inhabited by fishermen. Gayoom was a graduate of al-Azhar university in Cairo, Egypt.

Resorts or silos?

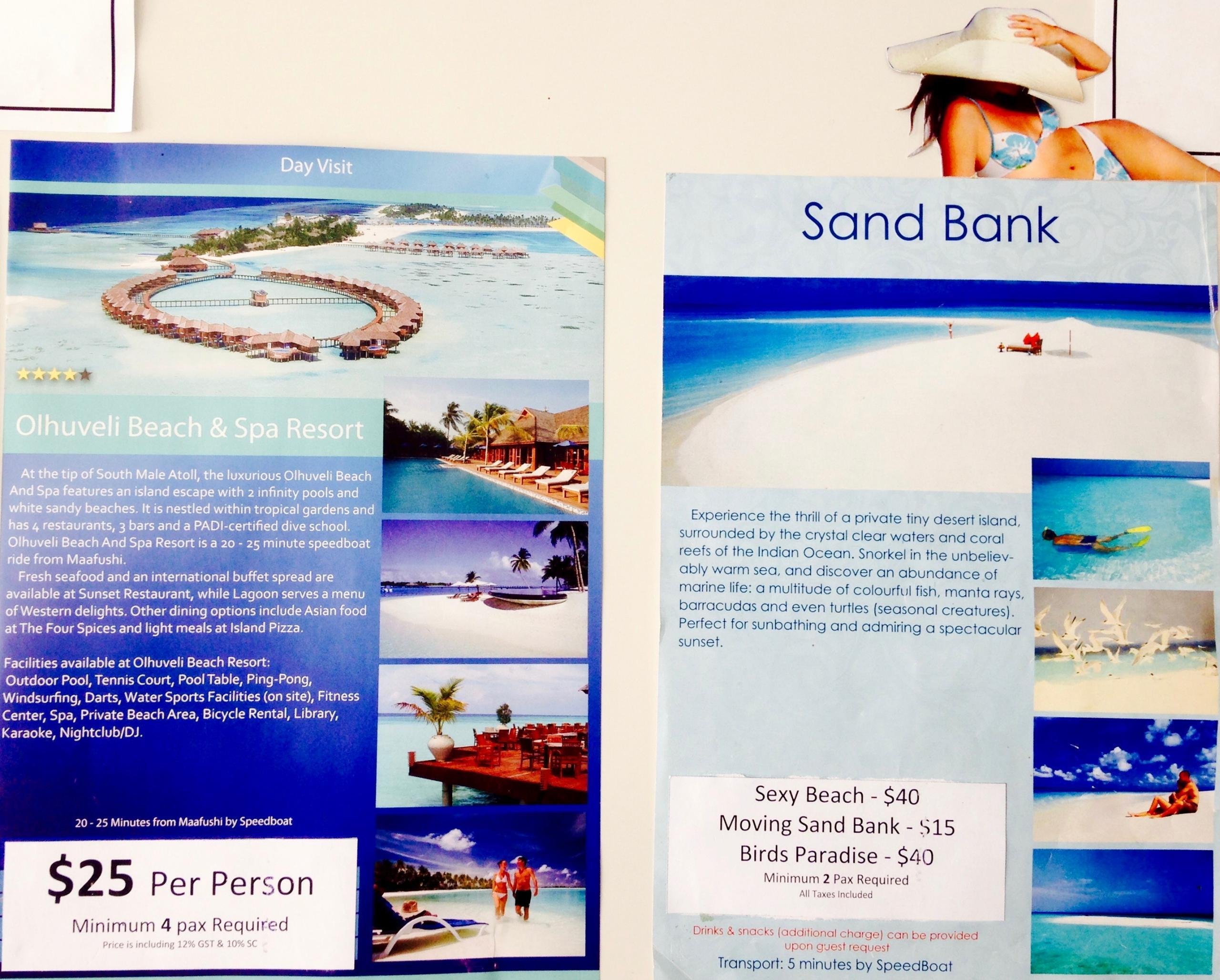

Gayoom was the architect of the resort model, the USD 5,000-per-night tourism. It was a way to develop the country, but also to control it by concentrating the population in Male and preventing contact with other cultures.

Out of the Maldives’s 1,192 islands, just 199 are inhabited and 111 are for resorts only. There is no interaction whatsoever between islands – not even inside the resorts. Off duty employees are forbidden to hang around.

Foreign businessmen build the resorts, but the law requires them to work with a Maldivian associate – who often has friends in parliament or sits in parliament. Thus, the richest 5 per cent of the population owns 95 per cent of the overall wealth.

Thus, any opponent is not simply an opponent: they’re an infidel. As Shahindha Ismail, director of Democracy Network, a human rights organisation, says: “Religion has been politicised, and politics sacralised.”

Ready for paradise

The result is that many, many young men today are like 25-year-old Ali. Soon leaving for Syria, Ali has a modest look. He is slim, wears flip-flops, jeans and a Koreana neck shirt. He sports a short beard. He is a private, shy guy. And he is ready – he has nearly saved the USD 3,000 he needs for the trip, from dealing hash.

Ali has never been abroad. Now, his phone is full of maps of Turkey. He follows the battle for Aleppo minute by minute; he knows everything about the frontline. He knows less about Syria. About its complexity – the rebel infighting, the secular activists, the lootings, the smuggling. In some sense, he is not going to Syria. He declares: “I am going to paradise.”

What does he expect to find? He has no doubts: “brotherhood”. A new life. A different life. “A society where we are all human beings, and not vultures, like here, where we exploit each other,” he says.

Belief and study

On the Islamic state he would like to live in, Husham knows what it shouldn’t be. He smiles when I tell him that in Europe, we say foreign fighters know nothing about Islam. I mention the British man who’s reading the book ‘Islam for dummies’ at the airport.

Islam is justice. We are not citizens: we are beggars. If you get sick, you knock at the president’s office, and you are paid a treatment abroad. Which is why nobody stands up, despite it all, because whatever your problem is, that’s how you fix it.MOHAMED (20), university student

“No Muslim, except for imams, would ever call himself an expert of Islam,” he says. “But the Koran starts by saying: study.” Then he looks at me, he says: “Like Kant, right? Sapere aude.” Dare to know.

Mohamed is 20 years old, and he looks like the university student he is: jeans, a polo T-shirt, and a shoulder bag. He’s in the faculty of Sharia law.

“Islam is justice. We are not citizens: we are beggars,” he says. “If you get sick, you knock at the president’s office, and you are paid a treatment abroad. Which is why nobody stands up, despite it all, because whatever your problem is, that’s how you fix it.”

But so why, I ask, he doesn’t start from the Maldives? Why Syria? “Syria, simply, is the priority,” he replies. “With 500,000 dead, it would be strange…to focus on ourselves rather than on Syria.”

Double standards

In the Maldives, only Muslims can be citizens. Islam is the main subject taught in schools.

But as much as Islam is present in Maldivian culture, it is also ignored. Five times per day, shops shut down for prayer; but clerks stay inside drinking coffee instead of going to the mosque. The same double standard exists for alcohol. It’s banned, but the Island Hotel next to the airport sells it. The Minister of Islamic Affairs has been filmed with prostitutes. But a woman who engages in sexual relations outside of marriage will be flogged in front of the court of justice.

None of this information, of course, reaches the tourists.

Four Italians on a beach

I’m now in Maafushi, a hour ferry ride from Male. Four Italians are wandering around the so-called “bikini beach”, the beach for foreigners. They have just arrived, two divorced businessmen with the two twenty-year-old sons of one. They had no clue that the Maldives is a Muslim country. It is also an ISIS hideout, I say.

“Shit”, exclaims one. Then he turns to his friend: “There’s the Islamic State here. No women.”

It’s not only about women. In Maafushi, there is nothing. In 2012, Nasheed was toppled by a coup, and that’s how the current government is trying to boycott guesthouses: same taxes of resorts, where a double room, is not a hundred, but a thousand dollars per night, and zero investments on the islands.

Besides the beach, Maafushi has just a few cafés. “In the evening, the only pastime is the crabs race,” says Andrea, disheartened. “You pay just for the brand. Just to boast that you have been in the Maldives.”

Islam replaced Buddhism

Most women wear a niqab. They are completely covered, draped in black. “This kind of Islam, so extreme, is an innovation rather than a tradition”, 30-year-old Mariyath Mohamed tells me. She’s a journalist.

Islam here replaced Buddhism. Even though the National Museum was attacked, in 2012, and its statues smashed, you just need to get into the oldest mosques. They were temples: the Mecca is pointed out by the floor’s tiles, added diagonally later on. Then, yet, Gayoom came. And not only Gayoom.

Mariyath tells me that after 1967, all those who went to study in Saudi Arabia, came back. That was after the Six-Day War, and the defeat of Nasser, of secular Arabs.

“For Gayoom, for his monopoly over ideology, they were a danger. And so, one by one, they all ended up in jail. They were all tortured. Killed. And turned into martyrs. In the mainstream view, they didn’t represent only Islam, but first of all, the opposition to a regime.” she says, and adds: “And then, the tsunami came. And now, this second tsunami, which is Syria.”

For the government, there is no such thing as fundamentalism. When the first two Maldivians were killed in combat in Syria in 2014, president Yameen turned down any responsibility. “We always recommend our fellow citizens to behave properly while abroad,” he said.

University or jihad

“The government doesn’t want a face-off, but somehow, it also shares some of these ideas. Like all of us,” says Ahmed Nazeer.

He is 25 years old, and one of the most renowned activists. He specialises in human rights. But he is also Ali’s cousin. And they are very close. But he’s not trying to stop him. “I can’t judge his choice,” he says. “For me, simply, it’s a lost war.”

For Nazeer, this war is not wrong in itself: it is wrong because it is doomed to defeat. So he is looking for a PhD in Europe.

“Here you can’t study. Literally,” he tells me. “Tourists have an entire island, and we don’t have a quiet corner to focus on a book.” He tells me that he has been photographed by tourists. They call it “colourful”.

We are on the beach of Male. It’s an artificial beach – poisoned, moreover, by the hospital’s sewage.

Kinaan is still ready to leave.

“To help the oppressed,” he says, “not to exterminate infidels.”

“One of our gangs is named after Bosnia. So many gangs, some day, will be named after Aleppo.”