Finally, after a long-lasting drought, the rains have come to Kenya’s Turkana region. But the rains are no longer the unequivocal blessing they used to be. In days gone by, the water would fall softly to the ground, gently nourishing the dry landscape back to life. Now, the sky releases enormous amounts of water, it is as if someone is using a high pressure hose up there. Where a few hours ago, the land was dry and dust-covered, the rain has gathered in brown-coloured rivers, burrowing its way deep into the soil, uprooting entire trees, overflowing roads and creating roadblocks. In no time, the landscape is transformed. Some people find they have become islanders, surrounded by water on every side and cut off from the world.

The Turkana region is situated in northwest Kenya. The region houses close to one million inhabitants, a majority of whom belong to an ethnic group of nomadic pastoralists, the Turkana people.

Threatning nomadic life

“We have lived in the outskirts of the Kakuma refugee camp for seven years now. Our life has changed; we used to live as nomads in the border areas near Uganda. Our livestock is dead, mostly because of drought,” says Veronika Ekori.

We have lived in the outskirts of the Kakuma refugee camp for seven years now. Our life has changed; we used to live as nomads in the border areas near Uganda. Our livestock is dead, mostly because of drought.VERONIKA EKORI, Turkana Woman

The Kakuma refugee camp is home to approximately 180,000 refugees from a range of countries, including South Sudan and Somalia.

Veronika’s neck is covered with brightly coloured traditional jewellery; in her arms she carries her youngest child. We stand talking among the huts that make up the families’ small farmstead, several of which are covered in plastic sheeting labelled “UNHCR”. Some of the family’s goats are grazing between the huts. The violent rains ceased after a day, and the usual hot sun is again beating down on the land.

“Today, we have only nine goats, but we cannot live on that, and we have to find alternative livelihoods,” Ekori continues.

Ekori is one of the few Turkana I talk with who have heard of climate change, which she believes is the reason they had to leave their nomadic life behind.

“Today, there is scarcely any food. We used to have camels, donkeys and cows, and we had enough milk, meat and blood. I prefer the nomadic lifestyle; living at one place permanently is very different. Our traditions go hand in hand with nomadic life, and without a livestock, we lose our traditions,” she says.

An impoverished place

Turkana is among Kenya’s poorest regions, with a poverty rate of 94,3 per cent. According to 2005/2006 statistics from the national Kenyan statistical bureau, less than one third of the men and below ten per cent of the women living in the region’s rural areas knew how to read and write. One out of three children had never attended school. These statistics are underpinned by Bernard Chamoux, head of the UN Refugee Agency in Kakuma.

“I have worked in Africa for more than 20 years, but I have never seen poverty as shocking as the poverty of the Turkana,” says Chamoux.

I have worked in Africa for more than 20 years, but I have never seen poverty as shocking as the poverty of the Turkana.BERNARD CHAMOUX, UNHCR

He admits there is a lack of competence regarding the best way to protect and develop this vulnerable area, and he criticises his own organisation for not having the needed expertise.

“The erosion here is like a tsunami, and we have to dig deeper by the day in order to find water. We have been here for 20 years, but none of us are experts on environment and climate. It is embarrassing, we are not very good on development,” says Chamoux.

The need to focus on expertise regarding climate change is also stressed by Eric Mativo, who up to January this year led the Norwegian Refugee Council’s environment program in Kakuma refugee camp.

“The problems linked to climate changes are discussed in Nairobi, but the knowledge does not reach us. Here in Turkana we often say that the government has forgotten us, as if we do not belong to Kenya,” says Mativo.

Conflicts lining up

The Turkana people feel that their way of life and livelihoods are under pressure from multiple sides: firstly there is fear that the plans to dam the Omo river, which flows from Ethiopia, will threaten the Tukana’s access to water as the river is the source of 90 per cent of the Lake Turkana water supply.

In addition, there is an on-going discussion about oil extraction. Some years ago, oil reserves were found in the area. Many among the Turkana are against extraction, mainly because it will occupy pasture land. They have little trust that the government will use potential oil revenue to improve the lives of the people here. There are already examples of corruption including Turkana land being sold off as oil blocs for extraction.

Another bitter conflict is the dispute about land rights in the Ilemi triangle, which comprises parts of Turkana, South Sudan and Ethiopia. In part, the dispute is traced back to a vague wording in a 1914 treaty aiming to secure free movement across the borders for the nomadic Turkana pastoralists.

Climate change and environmental damage have also contributed to increasing the level of conflict in the region. A study conducted by the University of Colorado shows that there is a connection between climate change and the risk of armed conflict in the so-called Sahel belt south of Sahara.

“My father was rich”

Atuko Ekeru Ebuum, an elderly man, introduces himself by presenting his ID card with his name printed on it. Ebuum functions as the informal spokesperson for a small community of hut dwellers living just outside the refugee camp.

“My father was rich; he had many camels, cows, goats and donkeys,” he says, and tells me that his family no longer have any animals at all. Today, the main income of the Turkana people living in this area is either selling driftwood or exchanging it for refugees’ food rations.

My father was rich; he had many camels, cows, goats and donkeys. Now we don’t have any animals at all.ATUKO EKERU EBUUM, an elderly Turkana

Ebuum has never heard about climate change, but, like everyone else, he speaks of the problems linked to drought and too little rain.

“Life used to be good then, we had a lot of food. Now it is difficult. Also, we had no church at the time, but our own traditional way of praying,” he explains. Originally, the Turkana are animists, which means they believe that everything, living and dead, has a soul.

Ebuum gladly reminisces about the good old days. He sits down on the characteristic small wooden stool the shepherds always carry with them, and tells us about the times when the rainy season was predictable and there was enough pasture for the livestock and the trees were full of fruits. He talks about rituals led by sages and sacrificing goats, and about how a man would have to pay several hundred heads of cattle in order to get married.

“Another problem is that this plant is ruining the goats’ teeth.” He points to a bushy tree with sharp thorns, the Prosopis Juliflora. This viable plant behaves as a kind of predator spreading out over the entire area.

Colloquially, this foreign species is called “Msumari wa norad” or “NORAD’s nails” in the Turkana language.

NORAD’s nails

The roots to the Prosopis problem, goes back to the 1980s. NORAD (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) was heavily involved in the Turkana district, and according to the book The History of Norwegian Development Aid (2003), NORAD at some point funded 80 per cent of all businesses in Turkana, including tree planting. The organisation spent more than 16 million US dollars on tree planting projects. According to the Norwegian environmental organisastion “Future in our hands”, a few local species were planted, but because of its resistance to drought, most of the projects focused on Prosopis. With its deep roots, Prosopis is able to find water where no other plant does, and thus it ousts traditional species and is a plant that would never naturally exist in Turkana.

The Kenyan newspaper Daily Nation has over many years written about how the toxic plant has turned life in the district into a nightmare. The poisonous sap makes teeth rot in goats’ mouths and the toxic thorns have mutilated many villagers.

“Nobody wants to take responsibility for planting the Prosopis. Once, a shepherd brought a goat to court to show how Prosopis had damaged the goat’s teeth. The pods contain a lot of sugar,” says Mativo. There are now on-going attempts to plant local tree-species in the area surrounding the refugee camp where the deforestation is particularly large.

Nobody wants to take responsibility for planting the Prosopis. Once, a shepherd brought a goat to court to show how Prosopis had damaged the goat’s teeth.ERIC MATIVO, Norwegian Refugee Council

According to Mativo, the Prosopis planting is not the only failed development project in Turkana. Another horror example is NORAD’s funding, at the end of the 1970s and beginning of 1980s of a huge cold storage for fish on the shore of Turkana Lake. Nobody had asked the Turkana, who traditionally live off meat, whether they needed a cold storage for fish. The storage soon proved to be too expensive and energy consuming to run and was left empty.

“When will you discover water?”

The list of problems caused by climatic change and environmental damage is long. Paal Lokone, Minister of Agriculture in Turkana West District, describes how cattle diseases, erosion and huge swarms of grasshoppers now follow in the wake of the rainy season and much more often than they used to.

“We have huge problems with food supply in Turkana. During the past ten years, we have not been able to grow corn, and importing is expensive. We urge people to grow plants that resist drought, like durra, says Lokone.

They have to dig constantly deeper in order to find water; it is not unusual to drill 200 meters into the ground.

A while after the rain stops, when the water has sunk, children dressed in bright colours play on a muddy field, digging their hands deep into the mud, making small wells and rivers, and running around. But it is not all play: they have brought cans to fill with the brown water.

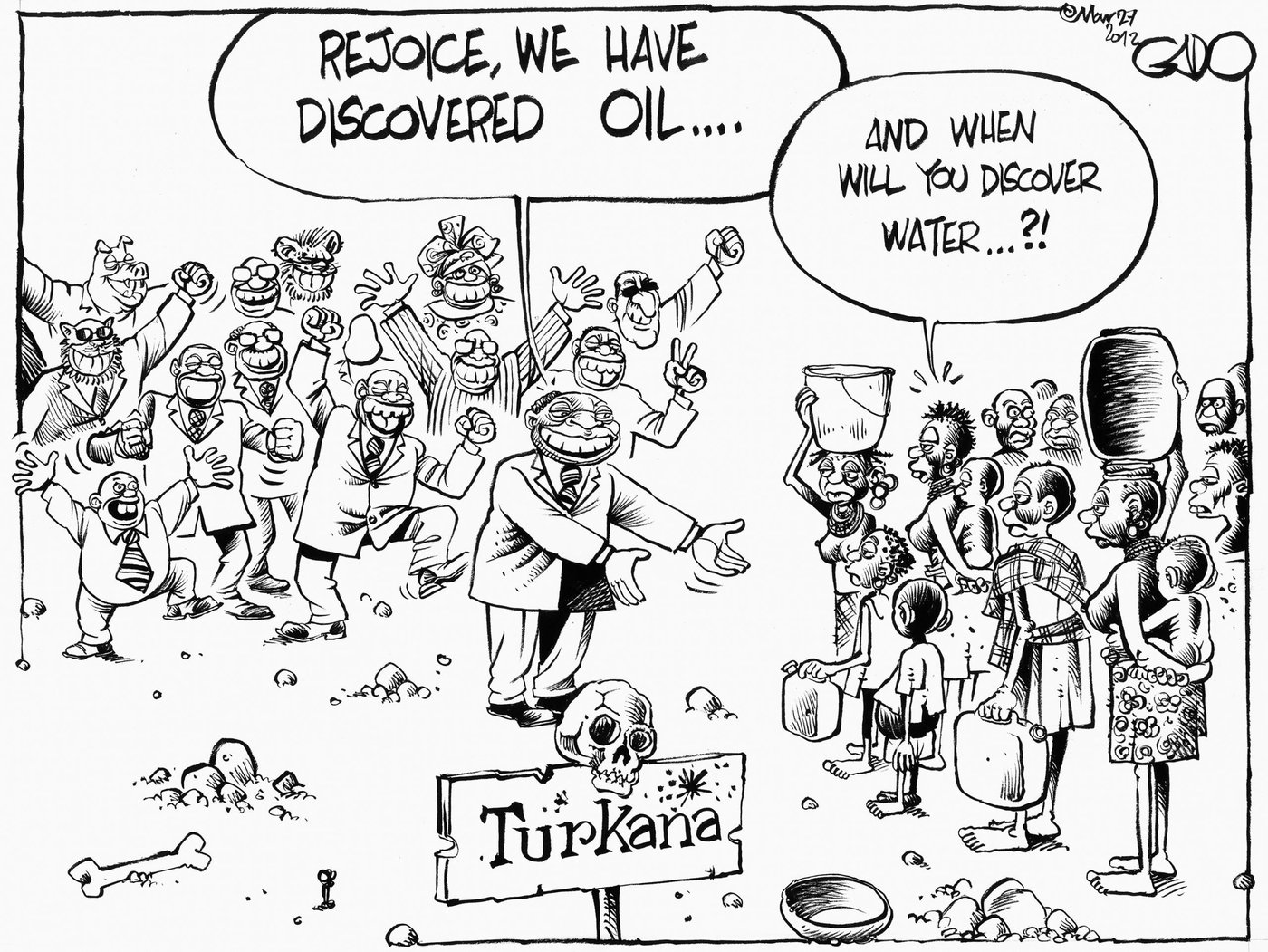

The sight of the children gathering water with such enthusiasm gives associations to a cartoon in African Geographical Review by the cartoonist Gado: The illustration shows an area littered with human bones – the remains of people who have starved to death. Fat men in suits and broad grins say to the lean, half naked Turkana people: “Rejoice, we have discovered oil..” whereupon the Turkana people answers: “And when will you discover water..!?”.