In 2000, the international community made a promise; by 2015, no child should be deprived of their right to education. As time is running out, 58 million girls and boys are still not enrolled in school – about 10 percent of the world’s children. Just over half of them live in sub-Saharan Africa.

“The international community has failed our most vulnerable children,” says Education Adviser Silje Sjøvaag Skeie in the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC).

A combination of risk factors keep children out of school – such as poverty, gender, disability and belonging to a minority – however, one risk factor has by far the most devastating effect on access to education: war and conflict.

It is evident that universal primary education cannot be reached without securing children in conflict and disaster areas access to education.DEAN BROOKS, Director of INEE

Half of all out-of-school children, or around 28 million, live in conflict-affected countries – up from 30 percent in 2000. In addition, millions of children are out-of-school as a result of disasters such as earthquakes, floods or storms.

The number one barrier

“The problem of out-of-school children is becoming increasingly concentrated in conflict affected countries”, states the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2015 from UNESCO, which monitors progress towards achieving education for all.

“It is evident that universal primary education cannot be reached without securing children in conflict and disaster areas access to education,” says Dean Brooks, Director of the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE).

During the past few years, the need to address the education needs of children in war, conflict and disasters in particular has gained increasing recognition.

“However, despite everything that has been said and done, there is a need for greater focus on this group of children,” says Brooks.

The joint UNICEF and UNESCO 2015-report: Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All, labels the response so far as “totally inadequate”, and blames lack of resources, effective policies and political will.

New development goals

2015 could prove to be a pivotal year for education in general and education in emergencies in particular, as the consultative process on the post 2015 development agenda comes to an end.

Our concern is that if we do not prioritise the millions of children and youth who are affected by war, conflict, disasters, and violence, then once again, we will find ourselves in a situation where we fail to meet our goals.DEAN BROOKS, Director of INEE

In May, the World Education Forum was held in Korea, defining the road ahead towards achieving education for all. The resulting Framework for Action, which will be finalised by the end of the year, highlights the need to maintain education during a crisis, by developing more resilient and responsive education systems that can withstand a crisis, and by responding to education needs in the early stages of an emergency.

On 6 and 7 July, the Oslo Summit on Education for Development will bring together recipient countries, donors, NGOs, civil society and the private sector to leverage new financial and political commitment to the education sector. Education in emergencies will be one of four main topics.

And ultimately, in September, the UN will adopt new Sustainable Development Goals – defining targets to be met by 2030, including for education. The new goals will replace the Millennium Development Goals, which have guided efforts since 2000.

Lack of focus

Neither the draft Sustainable Development Goals presented in July 2014, nor the proposed indicators, by which progress will be measured, presented in November 2014, explicitly mention the need for education in emergencies. It remains to be seen if this will change.

“Our concern is that if we do not prioritise the millions of children and youth who are affected by war, conflict, disasters, and violence, then once again, we will find ourselves in a situation where we fail to meet our goals,” says Dean Brooks.

Below we list the Top 8 Challenges preventing children in areas plagued by conflict and instability, from exercising their right to an education – as defined by the Norwegian Refugee Council.

The impact by war and conflict on education does not constitute a “hidden crisis” anymore, as UNESCO called it in 2011. It is time to act.

Gordon Brown, UN Special Envoy for Education, has stated: “In 2015, we must do more”.

1. Too little, too late

The international community still fails to adequately address education in its immediate response to emergencies. Traditionally, education has not been a humanitarian priority for neither aid organisations nor donors.

Food, water, health and sanitation were considered basic lifesaving assistance, while education, was something that should be left for later, when peace was restored.

“We know now that it is too late to wait with education until the emergency phase is over, and the development phase begins,” says INEE Director Dean Brooks, adding that: ”Increased focus has resulted in increased awareness about the need for education in emergencies. We see more actors engaging, however, so far, their interest has not been translated into enough concrete measures.”

Only a few countries – such as Norway, Japan and Belgium – have explicitly included education in emergencies in their normative policy documents and humanitarian aid plans.

Although more and more countries are following suit, the Overseas Development

Institute (ODI) concludes in its 2015 report; Investments for education in emergencies, that: “Among the donor community, education is still seen broadly as a development issue, rather than a humanitarian issue.”

We know now that it is too late to wait with education until the emergency phase is over, and the development phase begins.DEAN BROOKS

2. Big words, small bucks

Most international donors fail to put money where their mouth is. As focus and

awareness has increased, funding has declined.

In 2011, the global UN Education First Initiative set a funding target: Education

should get four percent of total humanitarian aid. At the time, education received

2,4 percent. Today, the number is a mere one percent.

Between 2006 and 2014, 75 percent of all humanitarian education aid was channelled through three UN organisations: UNICEF, WFP and UNHCR – that assume a mix of implementing and quasi-donor roles.

“The success of the education sector is thus highly dependent on these,” according

to a 2015 donor survey by Avenir Analytics, jointly commissioned by Save the Children and NRC.

Half the funds went to five countries: Sudan, Palestine, Syria, Somalia and Iraq,

according to the survey. Many of the top recipient countries represent protracted

crises.

“One central explanation for the negative development on funding is probably

the general decline in total aid, says NRC Education Adviser Silje Sjøvaag Skeie, adding that: “Education is still not considered integral to the first line of response.”

In an attempt to improve funding consistency and sustainability, Gordon Brown, the UN Special Envoy for Education, is now calling for a Global Humanitarian

Fund for Education in Emergencies.

3. Youth are overlooked

When discussing education in emergencies, we tend to focus only on primary school children, up to 12 years of age. Older children – youth – are overlooked.

Not even the soon to be replaced Millennium Development Goals include targets concerning secondary education or higher.

In addition to the 58 million primary school children who do not go to school, 63 million adolescents between 12 and 15 years of age have no access to secondary education. This is a huge number, considering that there are twice as many children as youth in the world.

In emergencies and protracted crises the humanitarian community often overlooks the young. They are seen as a challenge rather than an opportunity. That is a mistake. If appropriately engaged and supported, young people can serve as positive change agents to rebuild their communities and nations.ANDREA NALETTO, Education Adviser, NRC

“In emergencies and protracted crises the humanitarian community often overlooks the young. They are seen as a challenge rather than an opportunity. That is a mistake. If appropriately engaged and supported, young people can serve as positive change agents to rebuild their communities and nations,” says NRC Education Adviser ANDREA NALETTO, adding that we need to consider formal as well as non-formal education activities targeting the young.

NRC is one of few organisations that provide education opportunities to adolescents in all phases of a crisis – ranging from literacy and human rights education, to vocational training.

The war in Syria, where education levels are higher than in many other conflict-affected countries, has highlighted the need for university level education activities.

4. We fail to be accountable

Children and parents affected by conflict and disasters are clear in their priorities: They want education first. But the international community fails to deliver.

”In almost all my visits to areas ravaged by war and disaster, the plea of survivors is the same: ‘Education first,’ UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has stated.

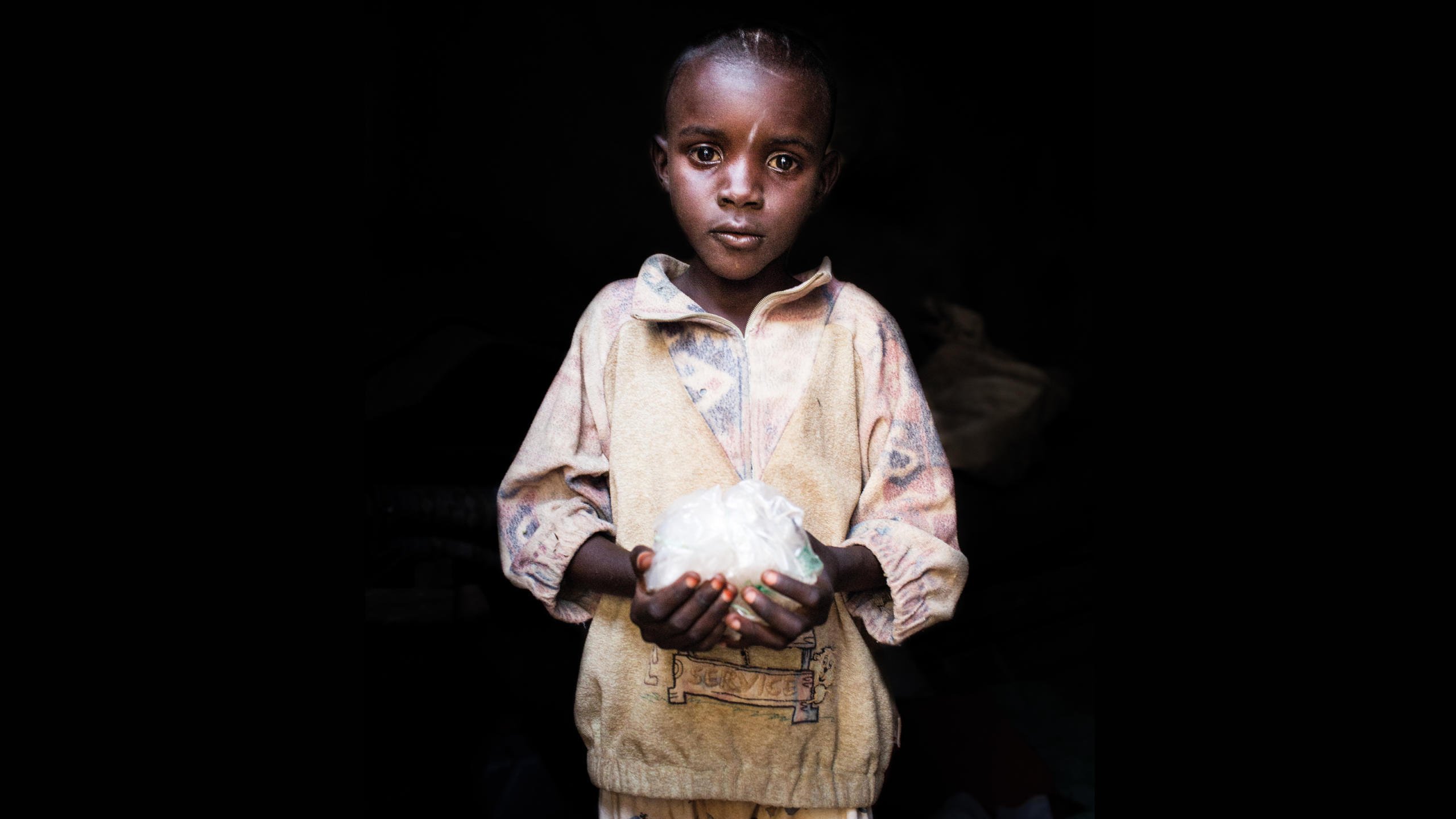

A joint study by Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children from 2014 supports his claim. Displaced people in North Kivu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Dollo Ado in Ethiopia were asked about their priorities; nothing scored higher than education. 30 percent put education at number one. Only 19 percent put food.

“If the humanitarian community is not providing what people are asking for, we are not accountable to our stakeholders. When it comes to education, there is today a huge accountability gap,” says INEE Director Dean Brooks, adding that

the gap is particularly dire in situations of protracted crises.

Because a crisis is not just sudden or transient, it is often a permanent state lasting entire childhoods. The average refugee spends 17 years in exile, according to the UNHCR, and an average conflict in the world’s least-developed countries lasts 12 years.

5. We need knowledge and innovation

There is an increasing amount of evidence on the importance of providing education in emergencies. However, we know too little about what actually

works in practice.

“More donors have become interested in supporting education in emergencies, and they are requesting more rigorous evidence on which models and approaches work, and which do not. If we wish to attract more interest and funding for education in humanitarian aid, we must, as a sector, be able to provide better answers,” says NRC Education Adviser Andrea Naletto.

More donors have become interested in supporting education in emergencies, and they are requesting more rigorous evidence on which models and approaches work, and which do not. If we wish to attract more interest and funding for education in humanitarian aid, we must, as a sector, be able to provide better answers.ANDREA NALETTO

In addition to calling for more research, he believes the sector must increase its focus on innovation.

“Addressing the many challenges of access, quality and equity requires more than business as usual”, emphasizes Naletto.

The education sector must, for instance, explore cutting-edge information and communication technology, as technological solutions can address many of the education challenges that occur in times of crisis.

“However, we also need to move away from the assumption that innovation equals new technology. We need to take an innovative approach to everything we do – from processes to programmes and partnerships,” says Naletto.

The education sector needs, for instance, to explore new ways of organising schools and classrooms in crisis settings. It needs to develop new teaching and assessment methods, as well as new approaches to teacher collaboration and the use of incentives that are adaptive to emergency contexts.

6. We fail to keep the schools safe

In too many countries, schools are battlefields, causing deaths and suffering, and keeping children out of school.

“In many countries, schools and universities, students and staff, are deliberately targeted. They are not just caught in the crossfire, but attacked as part of a strategy to defeat opposing forces,” says Diya Nijhowne, Director of Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack.

Between 2009 and 2013, armed state or non-state groups attacked students, teachers and education institutions in at least 70 countries worldwide, according to a study published by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack in February 2015. A significant pattern of coordinated and deliberate attacks was reported in 30 countries.

The study concludes that targeted attacks on education and military use of

schools are occurring in far more countries, and is fare more extensive than previously documented.

In many countries, schools and universities, students and staff, are deliberately targeted. They are not just caught in the crossfire, but attacked as part of a strategy to defeat opposing forces.DIYA NIJHOWNE, Director of Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack

“Apart from the fact that these attacks kill, they can cause fear and keep parents from sending their children to school,” says Nijhowne.

Attacks include the burning and bombing of schools, and killing, injuring, kidnapping, torturing or illegally arresting or detaining students and teachers.

The worst affected countries are Colombia, Sudan, Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan – where a 1000 or more attacks or military uses of schools were recorded between 2009 and 2012.

Norway and Argentina have taken the lead in championing a new set of Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, which were finalised in December 2014.

On 29 May 2015, a Safe Schools Declaration was launched in Oslo, committing states to endorse and use the Guidelines.

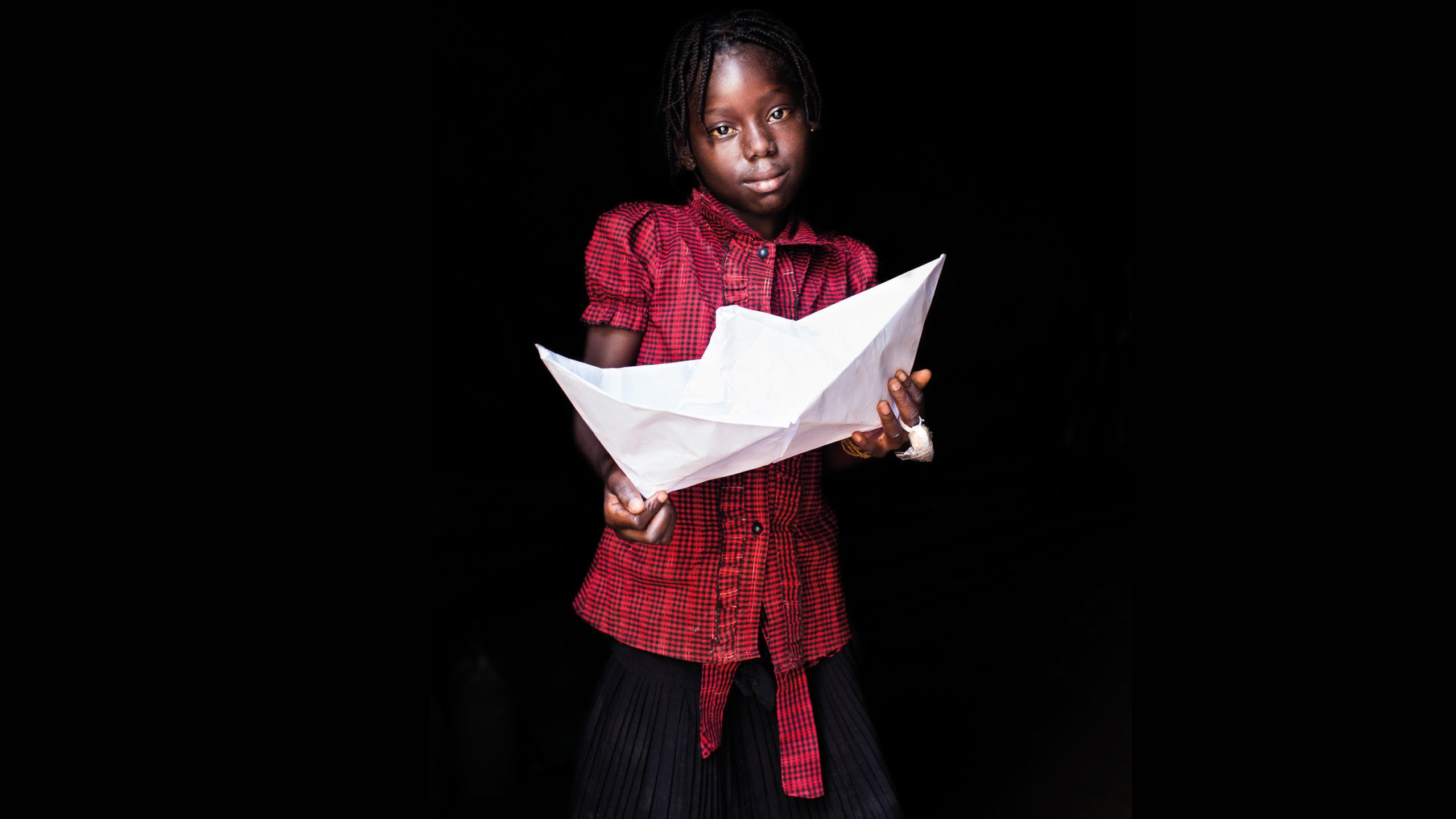

7. We fail girls

Girls are far more likely to be out of school than boys. This is particularly true in emergencies.

Progress has been made; between 1999 and 2012, the number of countries with fewer than 90 girls enrolled for every 100 boys fell from 33 to just 16.

“However, girls are still lagging significantly behind, especially in emergencies, says Education Adviser Silje Sjøvaag Skeie in NRC.

Factors that limit girls’ educational opportunities in stable contexts often intensify in crises – such as families prioritising boys’ schooling or girls dropping out due

to early marriage.

“Many education systems are male dominated and not sensitive to the needs of girls. Measures must be put in place to ensure that girls can participate and benefit

equally from going to school. Having female teachers, making sure that learning materials are not gender biased, or adjusting the timetables to the daily schedules of the students, are some ways of encouraging girls enrollment and retention,” says Sjøvaag Skeie.

Fear of harassment, rape or other forms of gender-based violence, as well as military presence in schools, is also contributing to pushing girls out.

“After a school has been occupied by armed groups, we almost always experience that girls are dropping out, fearing abduction and rape, according to the NRC

Education Adviser.

8. We are not prepared

Many countries have no plans for securing the delivery of education to affected populations in times of crisis – be it conflict, instability or disasters.

“All countries need such plans, but they are particularly important in areas with recurring crises,” says Annelies Ollieuz, Education Specialist in the NORCAP, the world’s leading emergency deployment roster.

The Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) is advocating for emergency preparedness to become an integral part of national education planning and policies – worldwide.

The network works closely with partner organisations and governments to adopt the INEE Minimum Standards for education in all education sector and crisis planning, and to adapt the standards to local contexts.

Countries also need to reduce the potential impact of disasters – for instance by having routines for early warning and evacuation of schools, and by constructing school buildings that are able to withstand strong winds, floods or earthquakes.

“We find that it is often more acceptable to promote emergency preparedness when it comes to disasters. It is much more complicated to convince states to include the same level of preparedness related to potential conflict,” says INEE

Director Dean Brooks, indicating that to focus on the potential for conflict may be politically difficult, particularly in states that have a history of unrest or internal strife.