Iat Anei Chol’s face reveals no emotion. The 17-year-old boy seems unaffected, though a little nervous, talking about his life as a child soldier. Six tribal lines extending from his forehead all the way to the back of his head, reveal his Dinka identity.

“I do not know how many I have killed. All I remember is dead people lying in the dust.”

Ethnic conflict

In July 2013, the president of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, sacked vice president, Riek Machar. In December the same year, Kiir accused his former vice president of staging a coup. Within days the conflict escalated into violent ethnic clashes over large parts of the country.

I do not know how many I have killed. All I remember is dead people lying in the dust.IAT ANEI CHOL (17)

In Malakal, Chol’s hometown in northern South Sudan, the political conflict led to war between the country’s two largest ethnic groups: the Dinka and the Nuer. The sand became red with blood and desperate screams penetrated the night. Chol lost family and friends.

Five years earlier, his father had left the family to dedicate his life to the army. One sleepless night, Chol decided to follow in his father’s footsteps. He could not stand being a passive spectator any more. A few days later, he had been issued with an AK-14 and was ready to fight.

“I had never held a weapon before, and it hurt to see people I cared about getting killed,” says Chol, in a small voice. He lowers his eyes to the ground.

He was not the only boy enrolled in the rebel group; half of the fighters were under the age of 15. The child soldiers were paid much less than the grown-ups, but money was not Chol’s motivation. It was all about winning against the Nuer and recapturing his hometown Malakal.

A fresh start

One year after Chol joined the armed group, the Dinkas retook Malakal and Chol decided that his fighting days were over. He decided to leave. In December 2014, using the money he had earned as a soldier, he bought plane tickets and took his mother and sibling with him to safety in Uganda. Somewhere during that flight, Chol decided what he wanted for the future. He wanted to go to school and become a pilot.

I had never held a weapon before, and it hurt to see people I cared about getting killed.IAT ANEI CHOL (17)

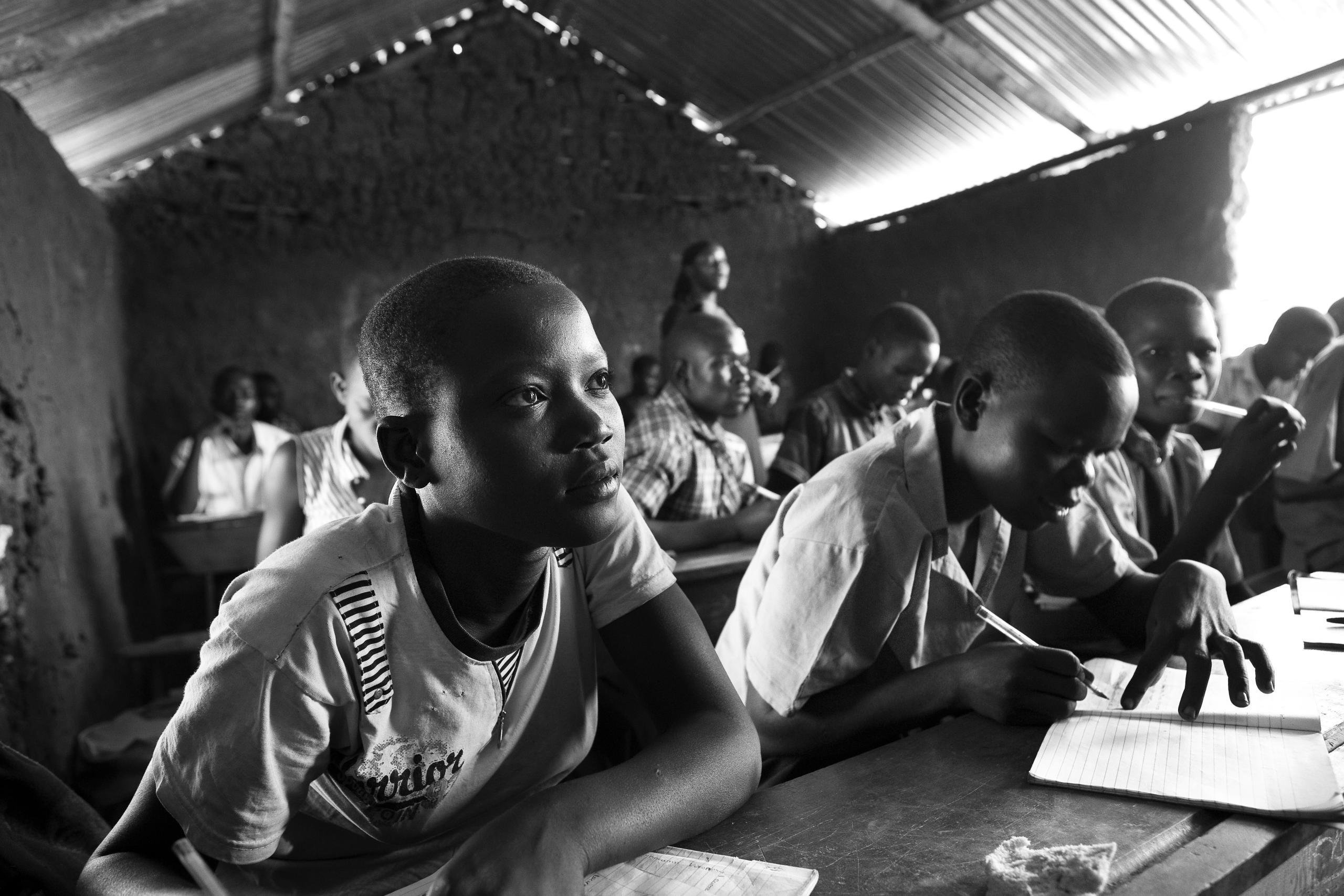

Chol is holding the chalk so hard his fingertips turn white as he writes the alphabet on the blackboard. It has been two weeks since he first put his foot in a classroom. Through the Accelerated Learning Program (ALP) conducted by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), Chol and other South Sudanese youth in the Adjumani district can make up for their lack of education. The refugee settlements in northern Uganda house a total of some 165,000 South Sudanese. More than 60 percent are under the age of 18, most of whom have no or very little school experience from before.

Three years

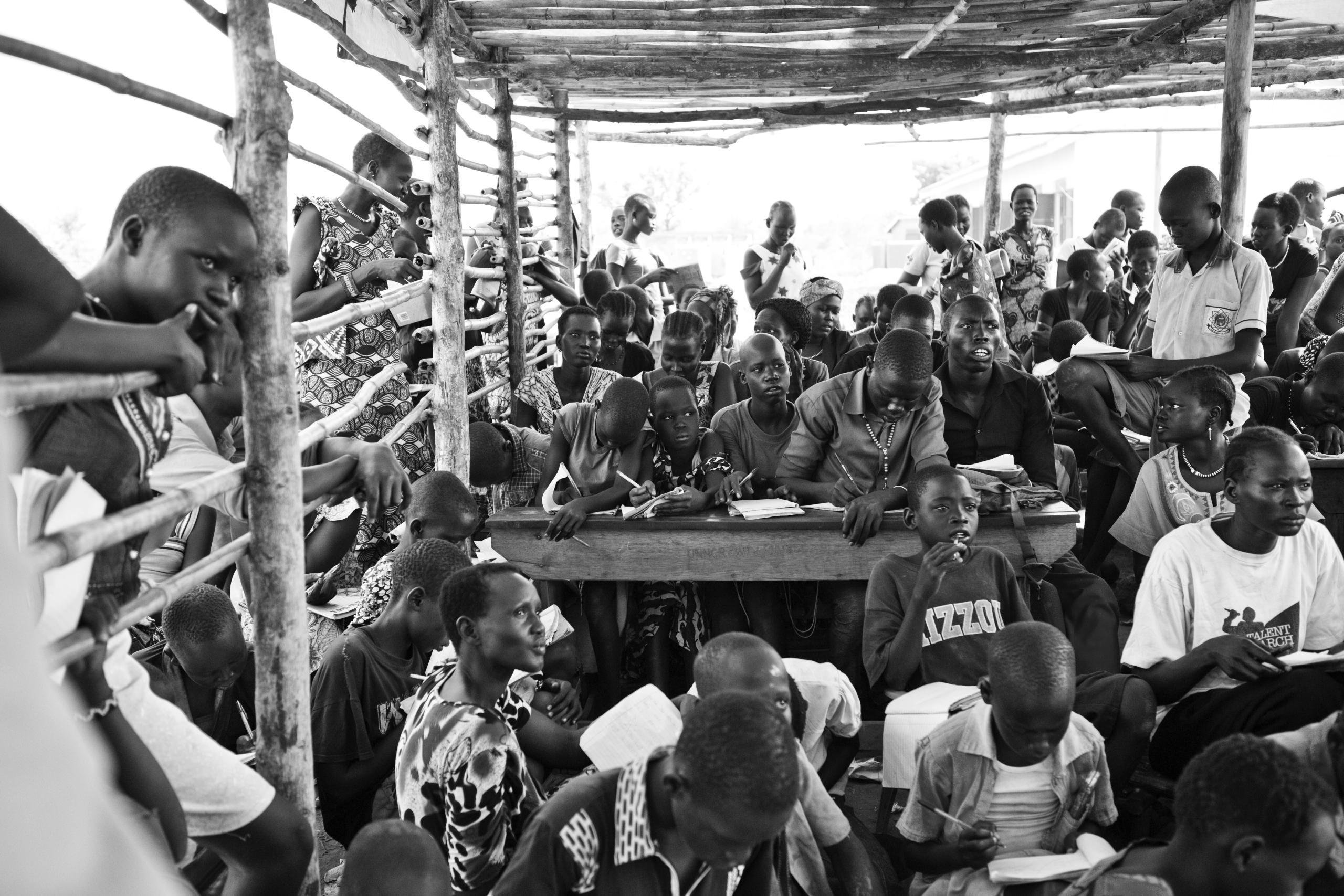

When school starts at 2 pm, the classrooms are packed. Latecomers stand on the outside holding their books, but their attention is firmly fixed on the teacher giving instructions up by the blackboard. Even though the ALP primarily targets youth, children and adults are present as well.

“The program is intended for youth between 14 and 17 years old, but we are flexible. Many are particularly vulnerable, and we have taken that into account,” says Nancy Lalweny, who is responsible for the education department at the NRC office in Adjumani.

The program is based on the Ugandan primary school curriculum, and provides students with the opportunity to finish primary school in three instead of seven years. The students are divided into classes depending on their prior education level. Some of the students are illiterate, while others have completed several years of primary education in South Sudan.

The teachers’ challenges

Alima Abas has just got the students started on today’s lesson. She is one of the new teachers hired to teach classes in the AL program, and she is looking forward to the task ahead. However, she also sees challenges.

“In every class there are students from different ethnic groups. They speak different languages and have different needs. The challenge is that there are too many pupils and too few teachers. The motivation of the students and the fact that nearly all of them have decided on a profession, makes it easier,” Abas says, as she helps the students who are lining up to have their notebooks corrected.

Child bride

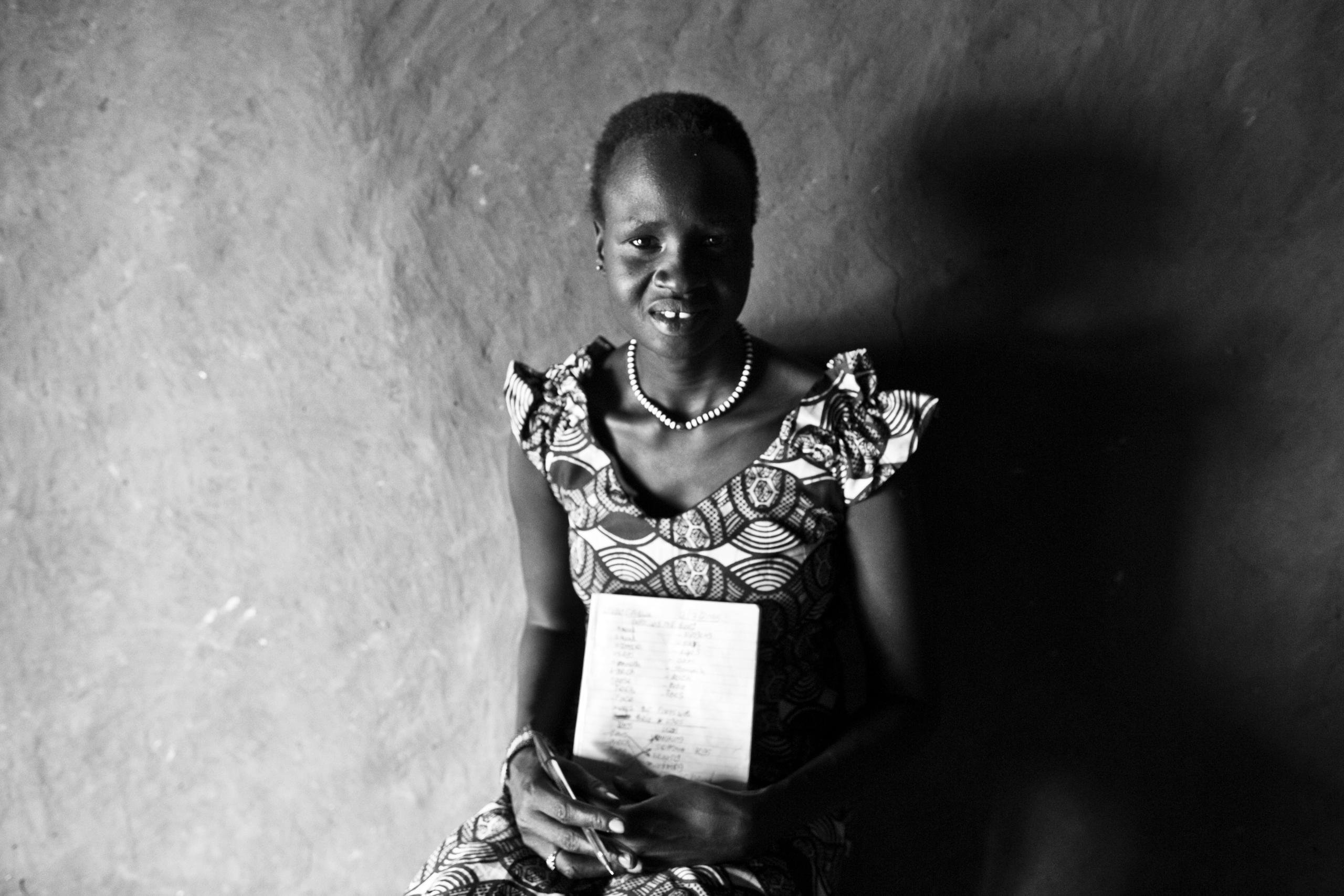

Strong winds sweep across the red African soil, whipping up a blanket of dust that settles over the open landscape of the Nyumanzi refugee settlement. 17-year old Amam Wach Ajang looks quite young, her eyes are full of live, but her smile is cautious.

Since her family arrived in Uganda four months ago, her life has been turned around.

“I was 13 years old when I got married. Even if I was not happy on my wedding day, I was proud to be helping my family. They received 55 long-horned cows for me,” Ajang says, looking down at her legs, moving them back and forth in the sand.

Escaped through a hail of bullets

Within a year, Ajang had given birth to her first baby. By her 15th birthday, she was the mother of two. When the war broke out in December 2013, she fled with her children from her home in Lakes State, across the White Nile into Jonglei State to the east.

“We threw ourselves on a fleet. Bullets were flying over our heads. Several times, we had to hide under water in order to avoid being hit. I saw many, children and grown-ups, who were shot and drowned,” says Ajang.

They spent almost two days on the river, without any food or water. When finally they arrived at shore on the other side, they began walking towards Uganda - and safety.

Now I dream of speaking English fluently. Imagine how it would be to one day become a doctor or an accountant.AMAM WACH AJANG (17)

Taking care of her children

Her husband remained in South Sudan to fight, but Ajang is optimistic about the near future for herself and her children. Getting married and becoming a mother meant she had to leave school in fourth grade.

“Now I dream of speaking English fluently. Imagine how it would be to one day become a doctor or an accountant!” she says, casting a glance around the classrooms. Ajang is in the first year of ALP. After three years of accelerated education, she will have completed primary school and will be able to apply for further education.

“I cannot say I miss South Sudan or my husband. When I married, I thought about my family’s future. Now I am thinking about my own,” she says.

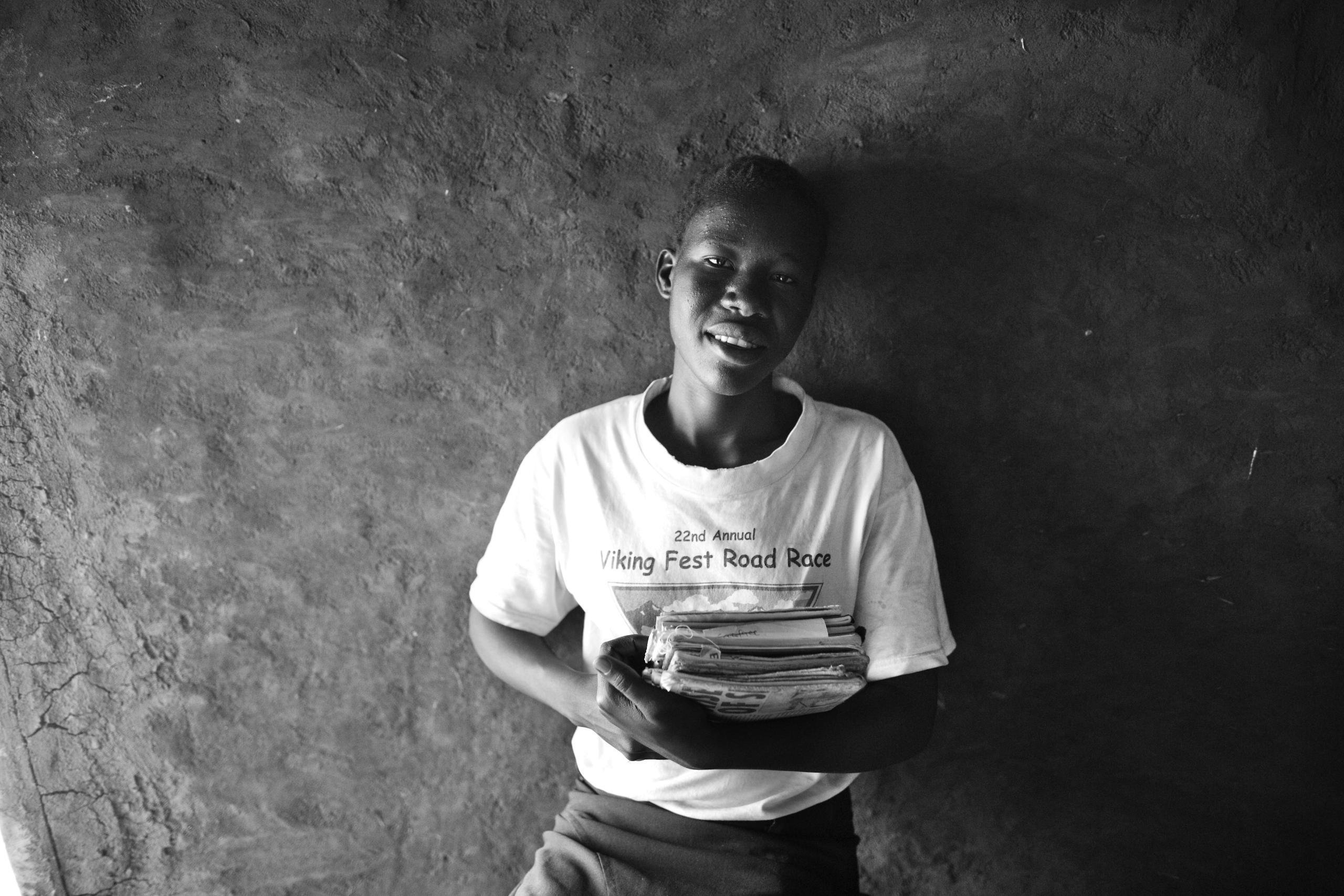

Fled with three children

In the refugee settlement, Ayillo II, hidden between two trees, stands a straw hut with a young girl sitting outside. 18-year old Christine tries not to think too much about the past. She was only a little girl when she lost her parents to the war. A few years later, she had no relatives left. She married at 15, but was soon left by her husband, who took to arms, wanting to do his duty towards his people and country. Christine began producing local liquor in order to support herself. One day, she received a visit from her cousin and her cousin’s three children. Then, without warning, her cousin left, leaving her three children with Christine. Over the next days, Christine tried to contact her cousin, but she has not heard from her since. When the violence reached her hometown of Moli, Christine escaped together with the three children and crossed the border into Uganda.

Education is the only thing that can save me.CHRISTINE (18)

Education is the way ahead

The inside of the tukul is clean and tidy. She built the round straw hut herself. On a table in the middle of the room lies a bag filled with school books - books bought with money she made from producing and selling spirits. She picks them up, one book at the time, browsing through them, over and over again. Christine is in the third year of the Accelerated Learning Program. If she does well on the exam, she will be able to apply for further education. She dreams of creating a future for herself and her cousin’s children.

“Education is the only thing that can save me. I hope, of course, someone will help me with the children, but as long as I have them, I have to make sure they are ok,” she says.

Chol, Ajang and Christine are three among thousands of South Sudanese refugees in north Uganda, who, because of war and poverty, have lost out on an education. Now they will have a new start.