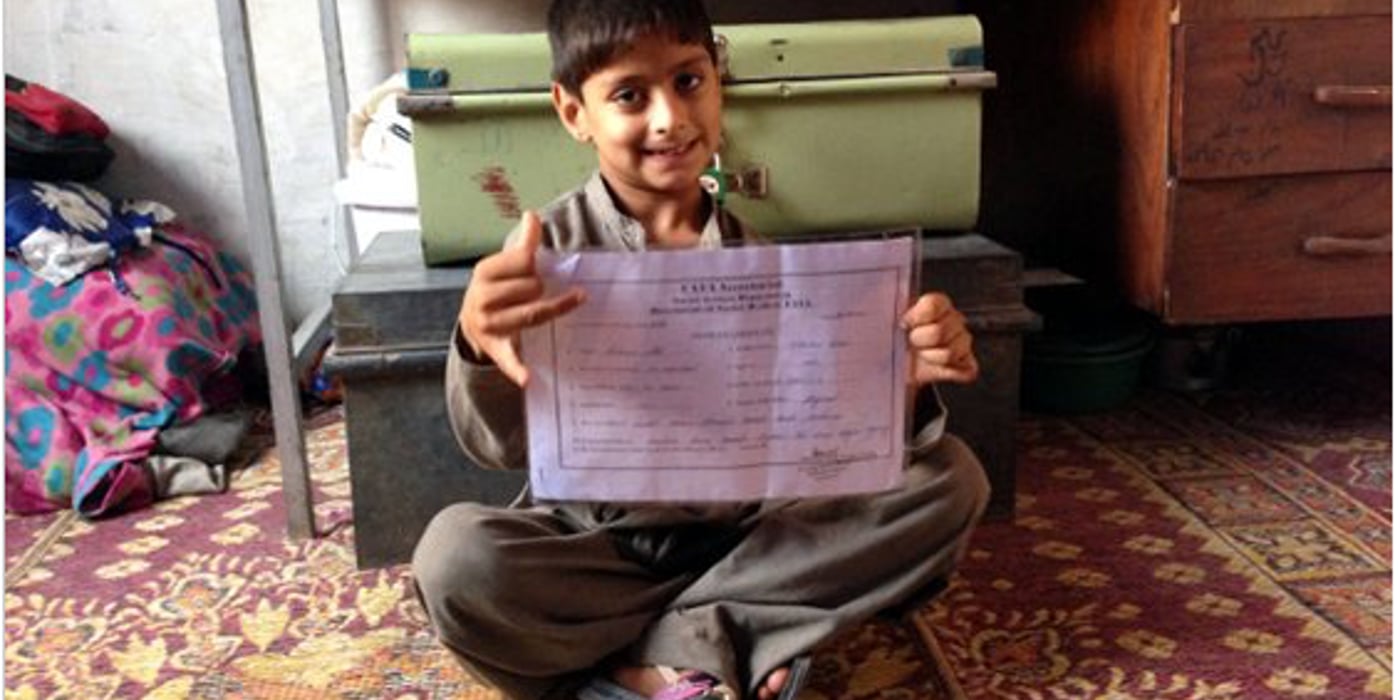

Mujeeb and Bibi Hajira, aged 10 and 9 years, are two of almost one thousand refugee children that enrolled in an Accelerated Education Programme (AEP) in the provincial capital Quetta, a programme designed by Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). Mujeeb and Bibi Hajira’s parents came to Pakistan along with their grandparents in the early 1980s because of security conditions in Afghanistan.

Mujeeb’s second chance

“A few years back I saw two brothers going to school. They were dressed in nice uniforms, holding new bags, and were discussing how they were re-joining school after the holidays. That day I really felt sad, and thought about how great it would feel to go to school,” Mujeeb says.

The AEP, which was established by NRC in Quetta in 2012, is designed to support children that have missed primary education to catch up and attain formal schooling at appropriate grade levels. Mujeeb was enrolled in the programme in 2015 and is ready to start his third semester this year.

“We are very happy with Mujeeb’s progress. His language has improved significantly,” Mujeeb’s mother explains.

In Balochistan, nearly half of the Afghan refugee children that enrol in primary education drop out before starting secondary school.

Mujeeb’s mother stressed that the family would not have been able to send their son to school without access to the AEP centres, where Mujeeb could enrol for free. As his father can only find work for ten days of the month at the most, the $10 USD daily salary is not enough to cover school costs.

Combating negative attitudes toward girls in education

Before Bibi Hajira attended the AEP course, her father was not in favour of female education. Her aspiration to continue her studies became challenging.

“My mother wanted to send me to a school, but my father did not. He said that a girl should learn to cook, to clean, and learn household chores,” she says.

“I cried and asked my mother to get me enrolled,” Hajira says.

Finally, the Parent Teacher’s Committee, which oversee the education activities in the AEP centers and works as community mobilisation structure, persuaded Hajira’s father to allow his daughter to enroll in the course.

“I was really happy that day,” Hajira says.

Her mother noticed positive changes in Hajira’s social conduct during her studies.

“Even her father is happy to see these changes,” her mother says.

I was really happy that day.Bibi Hajira, Afghan refugee child

A positive learning experience

Mujeeb still remembers his first day at the teaching centre. Being used to violent punishment from former teachers, he was relieved to encounter a safe educational environment.

“I was happy, but really scared to meet the teacher. I was quite relieved when the teacher shared that he will never beat us,” he says.

Now, Mujeeb is enjoying his learning experience.

“I can identify parts of the body, I can count, and I can even add,” he says.

Aspiring to become the best student in class, Hajira was also excited on her first day of school.

“I loved the stationary I got, and I am still keeping it safe with me. I loved my school,” she says.