In the north-western region of Kigoma, we met some of these students and their volunteer teacher. Here in Nduta camp, for every classroom there is a need for eight more.

Kevine’s story

Eight-year-old Kevine and her classmates sit on stones under the trees, eagerly copying down notes from sheets of paper tied to tree trunks. Cars roar by, kicking up dust from the road and making it difficult for them to concentrate. Noises from nearby classes pull their focus away from the teacher.

Kevine is one of 145,000 displaced schoolchildren in Kigoma. She misses her school in Burundi, a properly furnished building.

“But here,” she says, “we study under trees and we sit on stones. I feel sad because I do not have exercise books, pens, clothes, shoes or a school bag.”

Kevine and her family fled from Burundi in February after she lost her grandfather to the violence that has raged the country since 2015. When President Pierre Nkurunziza declared that he would sit a third term despite constitutional laws, protests and government forces wreaked havoc across the country.

Kevine’s mother worries that Kevine is still traumatised from the journey to Tanzania. She tells us that she hopes Kevine will attend school during their time in Tanzania before they return to Burundi.

We study under trees and we sit on stones. I feel sad because I do not have exercise books, pens, clothes, shoes or a school bag.

Niyongere’s story

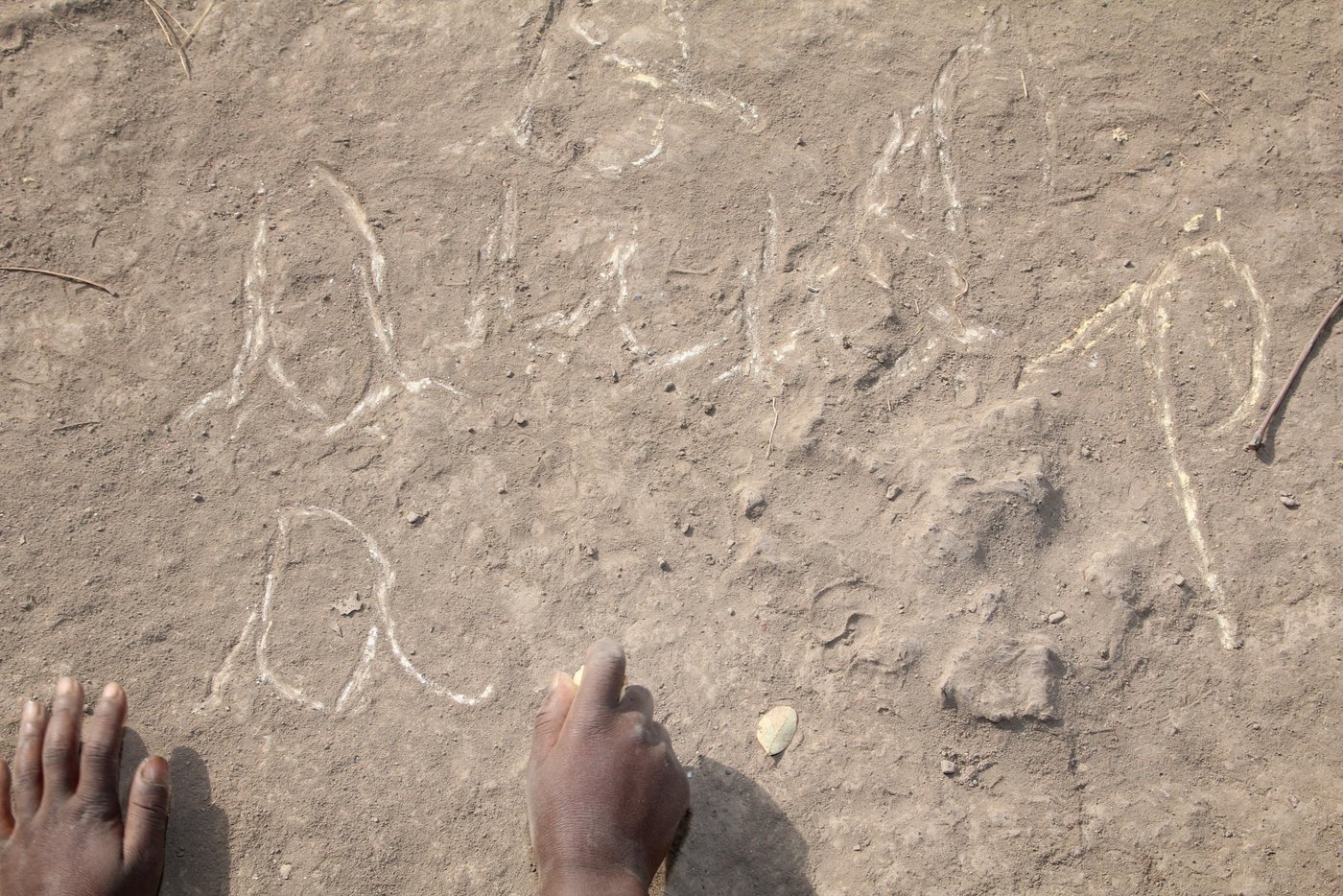

Niyongere, who’s ten years old, is eager to learn maths. Like Kevine, he has no notebook or pencil. He drags a small stone through the soil to practise his arithmetic.

“Maths help me learn how to count numbers,” Niyongere explains knowingly. “I can count from one to ten in Swahili, English and Kirundi.”

Niyongere fled Burundi with his parents, leaving their home in Muremera village behind. Armed men often came looking for his father. He would hide under the bed.

Even walking to school in the morning became dangerous. One day, his teacher announced that his classmate was killed on his way to school.

“They were hunting for us,” Niyongere says. “That’s why we decided to come here. I miss the school where I was learning and friends, home and relatives.”

Violette’s story

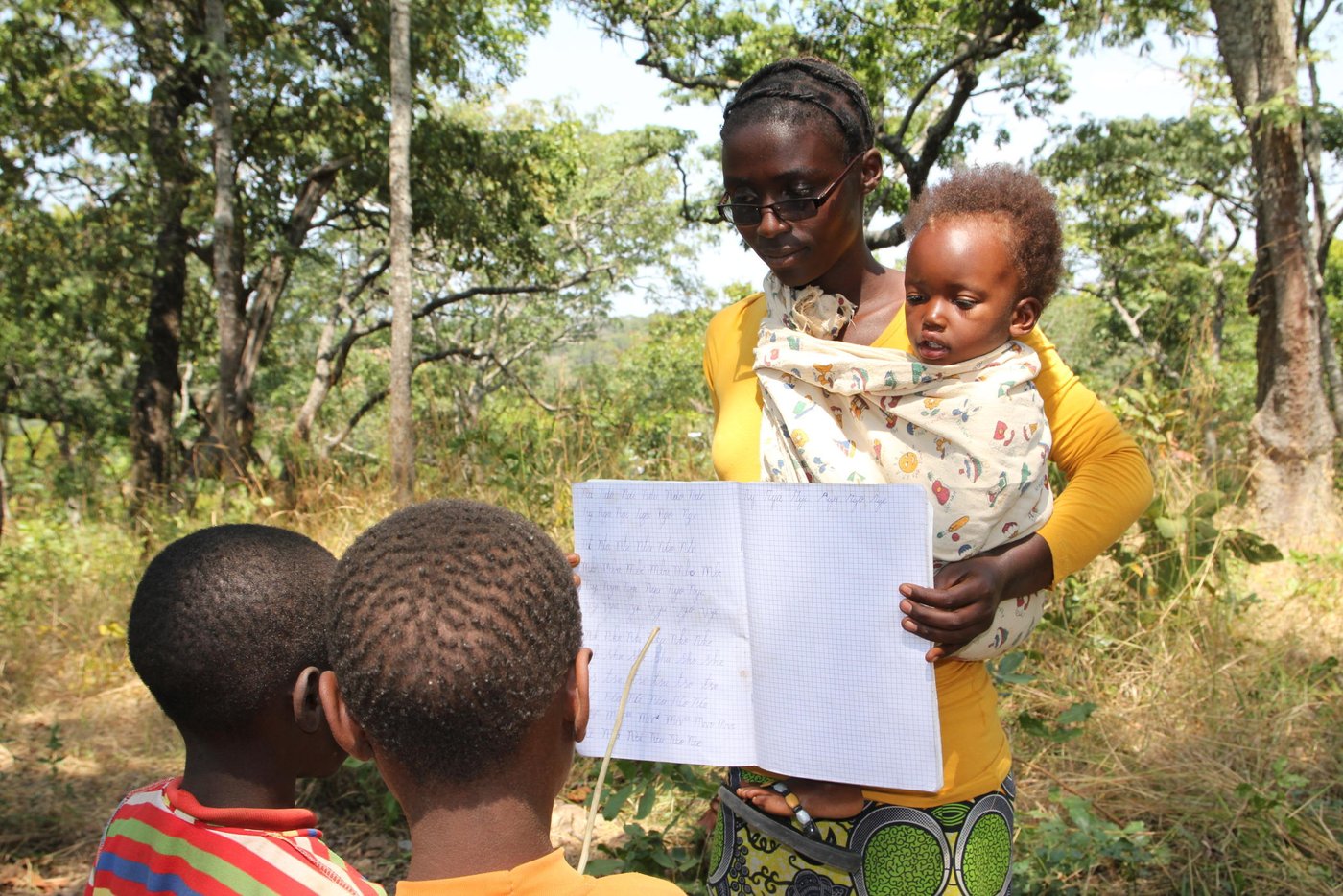

Violette is one of the students’ volunteer teachers. She’s a fellow refugee who fled Burundi’s Makamba province after members of an armed group abducted her husband. She fears that they killed him and dumped his body.

Violette had barely graduated as a teacher when she arrived in Tanzania. She teaches as best as she can, but the blaring lack of black boards and materials makes the job challenging. She’s not the only one. In the region of Kigoma alone, an additional 1,442 classrooms are needed to accommodate all the school-aged children.

This form of community-led education is in place to ease the burden of the camp’s NGO-funded schools – although as one of its many unpaid volunteer teachers, Violette struggles to make ends meets.

Violette always brings her daughter Bijou to work. Most times, she teaches with Bijou on her hip.

“I live alone,” she explains. “I don’t have anyone to help me taking care of my child.” But that hasn’t deterred her from volunteering.

“I like to educate children and I like to volunteer,” she says. She hopes that with these new experiences and new knowledge combined, they can one day go back to Burundi and develop their country.