Child soldiers

The number of child soldiers in the world is increasing – almost half of them are girls

In some countries, as many as 30 to 40 percent of child soldiers are girls. Norwegian researcher Milfrid Tonheim recounts her meeting with some of them.

Armies and armed groups know that children are easily lured or forced into service. It is not difficult to control children, who are used to trust and follow adults. They are also cheap labour.

In some countries, children are recruited to participate in war and conflict through mandatory, national military service. Sometimes children willingly recruit themselves, in the belief they will be provided with protection, food and a salary. However, many children are also forcibly recruited by armed groups in the chaos of war and separation from their parents.

Researched child soldiers in Congo

“I felt like I really had to go through with this research project. Some of the children have been subject to unimaginable, horrifying assaults,” Milfrid Tonheim says.

Researcher Milfrid Tonheim interviewed 17 Congolese girls who are former child soldiers. Most were recruited into armed groups through kidnapping. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

Researcher Milfrid Tonheim interviewed 17 Congolese girls who are former child soldiers. Most were recruited into armed groups through kidnapping. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

She began her research on child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) after she was offered a research position at the Centre for Intercultural Communication (SIK) in Stavanger, Norway, in 2008. Today, she is a researcher at NOCRE Norwegian Research Center AS.

“It took a while before we obtained the means we needed to get started with our research. Meanwhile, I worked as an adviser for a reintegration programme in DR Congo, which was funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. There, I gained some practical experience while researching,” she says. Her research resulted in a PhD thesis in 2017.

Most of the girls Tonheim spoke with had been kidnapped and forced to join armed groups. A few girls chose to join the groups themselves. One of them joined to avenge her father’s murder.

“As far as I know, no research has been done on this field. But in my interaction with the girls, it seemed as if the ones who had joined the groups on their own initiative were more often included in acts of war than those who were forced,” Tonheim says. “It might have something to do with trust: That those forcibly recruited are more likely to try to escape than the volunteers.”

Sexually abused

Tonheim explains that girls often have several different tasks and roles. Some are combatants. Others are for example used as spies. They also have the same tasks that they would have back home: doing laundry, cooking and fetching water.

Although boys are also sexually abused, girls surpass them by far. Some girls are given away to a male soldier or officer, some become sex-slaves for one or two men, and some are free to sexually abuse by anyone who wants a girl for the night.

“Some of the girls have given birth to a child or two after being raped. The ones I interviewed loved their children deeply. Their children were extremely important to them. Their eyes lit up when they spoke about their children, although they were also worried about them. Their love for them was clear for the world to see. It was both tough and extremely beautiful to witness.”

Each time Evelyn, 18, has to repeat her story, she opens a sore wound. Photo: Truls Brekke, Perspective No. 1./2009.

Girls receive less help

“To receive help, you usually need a demobilisation document confirming that you are a former child soldier. In DR Congo, most organisations working with demobilisation and other initiatives for former child soldiers require this document. But the girls who escaped on their own don’t have it. As a result, they feel very alone,” Tonheim says.

She claims that girls are generally overlooked in the process of freeing child soldiers. Most freed child soldiers are boys. The majority of the girls escape on their own.

“This is because you have to cooperate with the commanders to free the children: UNICEF and other organisations doing this kind of work receive lists with names of soldiers under the age of 18, who needs to be rescued. The girls’ names are often not on those lists, because the commander or the soldiers view them as their wives or mistresses.”

Tonheim believes that the problem is largely due to the fact that the world – and not only the armed groups – have a tendency to cling to some kind of standard idea of what a child soldier is:

“If you assume that child soldiers can only be fighters who carry guns, many girls are excluded. But girls have more tasks and roles. Thus, they don’t receive the help they are entitled to.”

I refused, but then he ordered a young soldier – a child – to kill me too. I was afraid they would kill me. I used my panga (knife) on my father. I chopped him to death.

Josefine Anyeko (19) tells us when rebel soldiers forced her, thirteen year old girl, to kill her father before they kidnapped her.

From the magazine Perspectiv No. 1, 2009.

To escape on your own is dangerous. “Many of the girls risk their lives,” Tonheim says. In some cases, their escape can also affect other people’s lives: If the girl is pregnant, she can risk harming her unborn child. If she has already given birth, she may have to flee with her child on her back, adding an extra burden to the journey.

A former child soldier with her daughter in Nepal. The civil war is over, and the young woman was released by the Nepalese government, the UN and former Maoist rebels who agreed to release the child soldiers as part of the peace process in 2006. Now, the future is waiting. Photo: AP/Binod Joshi/Scanpix

Tonheim also explains how other child soldiers can be harmed as a result of another one’s escape:

“You risk the lives of your friends if you flee. That’s not an easy decision to make.”

Fears stigmatisation

Many girls escape on their own because they do not want anyone to know that they have been child soldiers.

“This is a difficult balance. Because as a girl and child soldier, you have crossed some gender boundaries. You have also been in a group that people view negatively. That’s why you will experience stigmatisation.”

Several girls Tonheim interviewed said that they had hoped to return home to their village and family – without anyone knowing what they had really been doing while they were away.

“But it’s very, very difficult. The vast majority of the people in the village know who have been abducted – it's not something that is easy to hide. So even if the girl comes home on her own, many will still jump to their own conclusions.

A tough and difficult process

Regaining a normal life is a tough and difficult process that takes time. Tonheim explains that, naturally, some of the children and adolescents may have changed during the time they have been away. A lot may have happened at home too. And your village may be in a war zone.

Christine, 18, is now given the opportunity to go back to school and learn to become a tailor. Photo: Truls Brekke - Perspective No. 1/2009

“Out of the girls I talked to, there was one who had been a child soldier for only two days before she managed to escape. Even she spoke about the stigma she experienced afterwards. The girl who had been there the longest, was there for four years.

The girls also spoke to Tonheim about what it was like coming home:

“There were some heart-breaking stories. On the day the girls came home, many families expressed surprise and great joy. But after a while, many of the girls experienced rejection. Many shared painful stories. Just imagine: You are kidnapped and have to live a brutal life in the woods - while dreaming about your mother and father, and longing home. And then that’s the homecoming you get. But sometimes there are happy endings, too.”

Labelled as dangerous

The girls have to deal with prejudices and taboos. It may be touch for the family to realise that the girl who has returned home is not a virgin anymore. It won’t be easy for the parents to marry off their daughter. Also, they won’t receive a bridal prize for her, and she becomes a financial burden.

Tonheim thinks the girls themselves are acutely aware of this fact:

"Maybe she thinks: “I'm not welcome anymore”. If she has children, the situation becomes even more difficult. Perhaps the parents see their child as a child of rebels, a child they don’t want to have around.

The girls are often met with horror, too.

“It depends a little bit on how long she stayed with an armed group, but the family may see that she has developed a different behaviour than she had before. She may behave more masculine," says Tonheim, and continues: “It's about jargon, clothes, language.” Thing that are easy to stigmatise:

“The girls are often labelled as violent, aggressive and dangerous.”

Through dance and song, Evelyn takes a new step towards a worthwhile life every day. Photo: Truls Brekke - Perspective No. 1/2009

Milfrid Tonheim stops to think for a moment before she adds:

“The picture you're left with from films and media is so violent: That children who are soldiers are somehow more dangerous, more brutal than adult soldiers. That they don’t have any barriers. But that is not the reality for most people. Maybe for a few.”

I am left with the impression that many girls are very cautious. That they would rather hide their anger and grief than let it out. That they are retreating. Avoiding conflict at all costs.”

What we do through NORCAP:

Giving children their freedom back

Stener Vogt is one of the experts in NRC’s expert deployment capacity, NORCAP. Fifteen times, he has been sent to countries with crises or conflicts to help children who are used in war. He has worked to free several thousand child soldiers in Nepal, Chad, Liberia and most recently in South Sudan.

Our expert is working to give children their childhood back. In partnership with national governments and organisations such as UNICEF, Stener Vogt organises the processes that lead to children laying down their arms. He has just returned from South Sudan, where 210 children were released from rebel groups. Strangely, only three of them were girls:

NRC lend our experts from our expert deployment capacity, NORCAP, to other organisations. Here our expert Stener Vogt helps UNICEF liberate child soldiers. Children who have been released, get two goats each. The goal is to breed the goats and thus earn an income. South Sudan, June 2018. Photo: Stener Vogt/NORCAP

“I mentioned to the commander that I had heard that there would be more girls there. But he answered: ‘No, we only have some wives here, and those you can’t get,’" says Vogt, pointing to a major issue that affects girls in particular: they become "wives" or "girlfriends" and fall outside the official lists. Sometimes, the girls are very young, around 12-13 years old.

Girls do not get their freedom back

South Sudan has been ravaged by war and conflict since 2013. Over 19,000 children have been recruited to armed groups since the conflict broke out. Over the past few years, many children have also been released, but among them there are, most likely, very few girls. The girls often feel ashamed about having been abused, and therefore prefer to not be included in the official release processes.

Read more on South Sudan here.

The majority of those who are released are boys. The girls are often referred to as "wives" or "girlfriends" and fall outside the official lists. The girls might be as young as 12-13 years old. Photo: Stener Vogt / NORCAP.

The leadership of the South Sudanese army has made it clear that they do not want children in their ranks. There are still some children under the age of 18 in the army, but according to Vogt, they are few. However, there are several children in opposition groups.

“South Sudan experience it as stigmatising as a nation if they have children who are used in armed forces. The Equality and Social Affairs Minister in Boma State is a woman. She is a partner of ours, and is of course very concerned about this problem,” says Vogt.

The future

But establishing formal liberation procedures is just the beginning of the path towards a good future. What will happen to the children after they have laid down their arms? How do we ensure that they receive the necessary care and assistance? The NORCAP expert thinks it’s very important to strengthen the abilities of families and communities to handle the return of the children in the best possible way:

Pibor in South Sudan, July 2018: Children who have been liberated from an armed group replace weapons with tools. They have been training for eight months on how to repair and good maintenance of engines. Photo: Stener Vogt/NORCAP

“The children must feel completely confident that families and communities are strong enough to give them the protection and care they need. If the children don’t receive the support they need, they return to the warlords,” says Stener Vogt.

NRC helps children traumatised by war

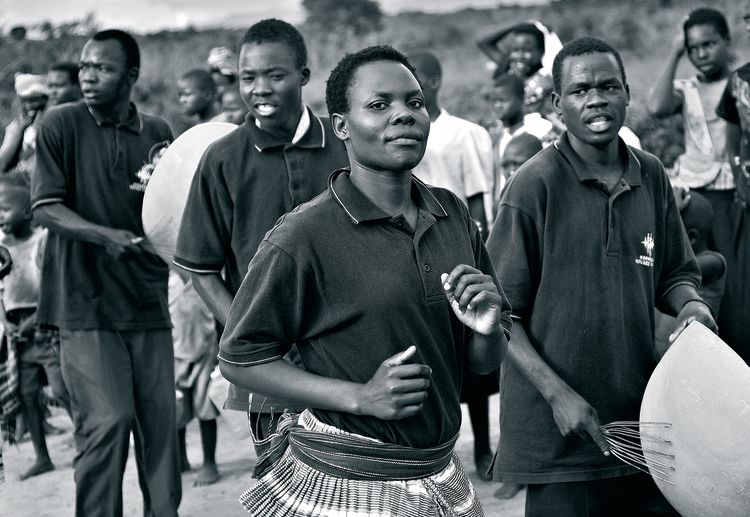

Education is one of NRC's main priorities. The "Better learning" programme helps traumatised children in conflict and war zones. The school programme started in Uganda - where it also supported former child soldiers. It has been developed in collaboration with the University of Tromsø.

“Children should not roam the streets - it can be dangerous. Instead, they should be in school where they are under supervision. The school provides children and youth with protection from for example being recruited into armed groups,” says Anneliez Ollieuz, who leads NRC's global education programmes. One of them is "Better learning".

Read the interview with her here.

The objective of the "Better Learning" programme is to help children who are struggling with painful experiences to be able to focus and learn in class. Children and adolescents with trauma have high anxiety and stress levels. We teach them several simple methods so that they themselves can regulate overwhelming emotions.

Jon-Håkon Schultz. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Jon-Håkon Schultz. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Professor of Educational Psychology, Jon-Håkon Schultz, led the efforts to develop the school programme.

Read the interview with him here.

He says that it is based on two main principles:

“The first principle is about helping children to calm down. Not just after they have had a war experience, but also later - when they think about what happened and are scared. The second principle is about rebuilding a sense of security.”

The programme is divided into three modules:

- Targets all students in the class. We help children to understand and handle common crisis situations.

- Focuses on all students who are struggling to concentrate at school.

- Helps students experiencing insomnia and nightmares.

– People of all ages are afraid of war. But children are particularly vulnerable, because they do not have the same life experience and cognitive ability to process war experiences. Therefore, they need extra help, says Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz.

One of the most important things we do in the "Better learning" programme is to create an environment where children can talk to their teacher about being scared. This gives the teacher the opportunity to calm down the children. The teacher can also help the child with social support, so that the child can be able to participate in activities both at school and at home.

We call children's reactions to war Normal reactions to abnormal situations. The reactions have in common that they reduce the ability to be able to concentrate at school:

- Fear

- Difficulty sleeping and nightmares

- Thoughts and images in your mind you do not want

- High levels of stress

- Reduced concentration

- Sadness, depression

- Social withdrawal

- Low self-esteem and negative thoughts about the future

- Anger

By using these relaxation methods, the children manage to control their own fears, concerns and nightmares.

Tension and release: Relaxation exercises that are designed to release muscle tension. The student spans parts of the body, such as arms, hands, face, neck, shoulders, belly, legs and feet. She keeps the tension for several seconds - before she lets go.

Breathing exercises: Exercises that help children to focus on controlling their breath. The student learns to breathe in deeply with her stomach and then slowly release her breath.

Safe space: Visualisation technique where we encourage students to use the imagination to create a place where they feel security, peace and joy.

Concentration and balance exercises: A series of postures, such as "palm", "tree" and "eagle". The exercises help children to focus on the connection between mind and body - and thus restore inner balance.

Stretching exercises: Different movements that stretch different body parts, such as the spine, neck, shoulders and chest.