A new solidarity?

The stories behind the Polish refugee welcome

Poland has welcomed over 3.5 million people across its borders since the escalation of the war in Ukraine on 24 February 2022, winning international praise. In this intimate insight into the homes of people hosting refugees, we revisit the concept of solidarity through the eyes of those on the frontlines of the crisis.

It was the Solidarity movement that started Poland’s peaceful revolution in the 1980s, opening up the country after years spent under Soviet rule. The memory of these events still lingers as hundreds of thousands of people now open their homes to Ukrainian refugees.

But behind the stories of welcome lies a more complex reality. Host families and refugees in Poland speak about the power of helping, and about their needs, dreams, guilt and shame.

A hundred days into the crisis, the cracks in this new solidarity are starting to show, as the volunteers and civil society organisations at the frontlines become increasingly exhausted.

At this turning point, it is time for Europe to extend its solidarity to boost support to people not only within, but also beyond the Polish borders. This is also the moment to look past national divisions and extend a welcome to those without a Ukrainian passport who are fleeing the conflicts and disasters raging in so many other parts of the world.

“They are humans, they need help,” says Irina as she looks over at Alex, one of her Ukrainian guests who fled the country on the first day of the war. But there is also a deeper, more personal reason behind her open-door policy.

“I came here from Moldova, all alone, 18 years ago,” she says, her voice breaking. “The Polish people just took me in. I lived at my friend’s place for about a year, and I got so much help. And I just thought, it’s time to give back.”

Arek, Irina’s partner, says his motivation is even simpler – driven by his Ukrainian roots, which stem from his grandparents: “I feel connected.”

On 24 February, the sharp sound of air-raid sirens ripped through Lviv’s morning air, tearing Oles and Alex from their sleep. “Mum, is it okay if we go to Poland?” One phone call later, their bags were packed as they rushed to the border.

“I am ashamed of myself for not helping Ukraine enough. It is a subject that still hurts me every day,” Oles says. He hears people back home say that men who have fled or stayed abroad are not real men, accusations that bore into his brain daily. “At some point you start agreeing with them. But you are 20 years old, you just want to live,” he says.

“Szyszka” (pinecone) was one of the first words of Polish that Oles learnt. When he and Alex managed to cross into Poland at Medyka, after many hours of anxious waiting and doubting if they would be even allowed to leave the country, he suddenly saw a huge pine tree right in front of him. The pinecone from Medyka is now resting by his pillow. He says it is his lucky charm.

Alex admits that even though the welcome they’ve received in Poland has exceeded everyone’s expectations, he worries that Europe’s positive attitude might change. There are social media reports emerging that accuse some refugees of being ungrateful.

“I also felt very guilty, like a bad person, when our first host family gave us a pile of clothes and I did not want to choose any of the old t-shirts,” he recalls. “Am I too picky? Should I just accept what is being offered because I am a Ukrainian refugee?” The new tag attached to his name feels complicated.

When the war started, Sylwia did not hesitate for a second. She mobilised the local community of her native Żyrardów, friends and strangers alike, to ensure that Ukrainians could experience the real meaning of Polish hospitality.

She manages the apartments that her friends made available to Ukrainian refugees, supplies food and clothes, arranges cross-border transport of goods, and organises online fundraisers. “Helping is like therapy,” she laughs.

Before the war started, Olena (right) and Sylwia were simply colleagues, meeting sporadically on business trips. Now they see each other every day.

The company they both work for has sponsored a temporary flat for Olena and her mother for two months, and Sylwia is going out of her way to make them feel at home. Both say that once the war is over, they are going to share a glass of wine in a restaurant in Ukraine.

“My house was bombed today. I don’t know if there will be a home left, a place for me to go back to,” says Olena, showing the images of shelling that left her apartment building in rubble that very same morning.

She admits the war has made her feel like a completely different person. “In Ukraine, I was a pretty good sales manager. I spent six years and all my savings building my dream home. I left it all there. Now I don’t know who I am, I don’t know what to do.”

Olena spent five days sheltering in a basement in Kyiv’s suburbs with her mother, Natalia. They decided it was no longer possible to hold on when they saw a missile flying directly above their heads while they were taking a brief break outside.

“Look at my mum – she is 65 and she has to rebuild her entire life here. She has me here, while her other child, my brother, had to stay in Ukraine. All of us are broken because our families are separated. We don’t know how to cope with this situation,” says Olena.

Natalia says nothing. There is only silence.

The other day, six-year-old Max and his mother Maria were window-shopping in the local mall in Żyrardów, a former industrial town near Warsaw, when the boy suddenly grabbed a mannequin’s hand. “This is going to be my father until I see my real dad,” he announced.

“We almost had to walk out of the store with the mannequin,” his mother recalls.

The Polish border guards post a daily tweet about the number of people stopped by the authorities while trying to “illegally storm” the border with Belarus, followed by another tweet praising Poland’s help to Ukraine. Activists warn about the ongoing loss of life and pushbacks happening hidden from sight in the depths of Białowieża, the primeval forest stretching across the Belarusian border.

Shamshul, who fled Afghanistan last year, was one of the few people who managed to pass the infamous crossing and apply for asylum in Poland.

Ever since last autumn, Shamsul has lived with Martyna and Bartek in Warsaw, together with their little daughter Mia and dog Alonso. They found each other through the Ocalenie Foundation, which runs a programme connecting refugees with host families in Poland.

The family jokingly admits their Afghan guest is the best flatmate they could ever imagine. Shamsul dreams about bringing his own children to Poland, saying: “All I’m looking for is a peaceful life.” He bursts into tears when he talks about the moment he was finally able to give them a call to say he was alive.

“I had a really tough time when the crisis at the Belarus border started. I just couldn’t believe that my nation didn’t want to help these people and was willing to let them die in the forest,” says Martyna.

Visibly emotional, she cannot stop the tears when asked if she believes that the ongoing story of welcome offered to people fleeing Ukraine will change anything in society. “When the crisis in Ukraine happened, I was super happy to see how Poland reacted. I thought, this is finally the moment when we open our hearts and minds. But then I cannot help but think how unequal it is.”

“I could not pack many things when I fled Kabul, but I brought this. It’s a memory stick with all the documents I need to get myself a new job. In here lies my future,” says Shamsul.

He quietly admits that it is hard for him to watch the unequal treatment that non-European citizens receive when compared to the outpouring of help for Ukrainians.

“Please do not get me wrong, I feel for these people like nobody else. Their lives are in danger,” he says, remembering the day he went to volunteer to help Ukrainian refugees to express his solidarity. “But we are also refugees. For the nine months I have been in Poland, nobody has touched my asylum application. I still don’t know what is going to happen to me.”

“Clothes are a way of caring for each other,” says Karolina, a Polish anthropologist who has written about the transformative power of clothes in times of war. She is one of the coordinators at a free shop for Ukrainian refugees in Warsaw.

Karolina argues that clothes are tools of care, but also empowering tokens that can create a sense of safety. “I wrote two books about clothes being taken away from people in concentration camps. Now I am working in a store donating things. It has come full circle,” she says.

Most of the women who fled Ukraine packed bags filled with items for their children, but very little for themselves. Karolina says she is touched by how the clothes transform the shop’s customers.

“Sometimes women are ashamed to admit that they have found some beautiful things for themselves and they sometimes try to hide them. They even cry,” she says.

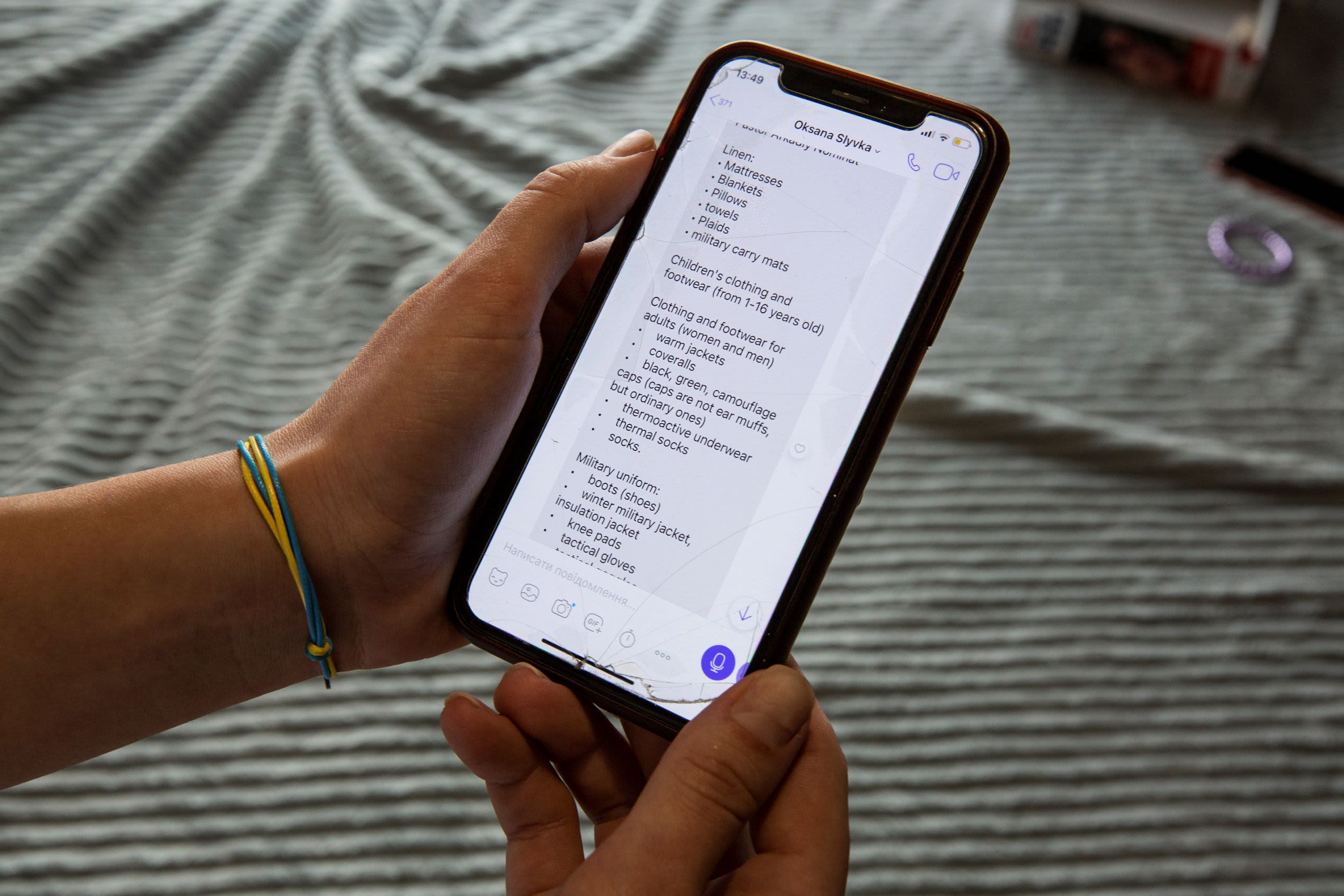

Ira shows us a list of the things requested by her father and brothers, who stayed behind in Lutsk, Ukraine, and run a transit point in their house for people coming from the east of the country. With the support of their Polish hosts, she and five other women do all they can to transport food and other essential items across the border.

Ira says that the ongoing effort is their way of giving back. “We had never been to Poland. We did not expect such a reception – we thought we would not be wanted, so we were shocked by how everyone accepted and supported us. We feel like a part of a big family here,” she says.

For Irina and Arek, doing good did not start with the Ukraine crisis.

“The last thing I would want to happen is for the world to look away from what is happening at the Poland-Belarus border because of our Ukraine response,” says Irina. “We cannot have it two ways: be a saviour to the people who look like us, and let the others die just a hundred kilometres away.”