A mother’s five-year fight for education

Lurexy spent five years fighting to get her oldest daughter Jesuanny, 10, a place in school. She is determined to make sure her other three children don’t miss out on those vital years too.

Lurexy introduces us to her children: “Jesuanny, my oldest, is the helpful one. Then we have Jesús. He’s the shy one. Luisy is the curious one. And my youngest, Jeremiah. He’s two. He’s the hyperactive one!” she says, as she comically exaggerates a look of exhaustion.

Lurexy and her children live on the outskirts of the Colombian city of Cúcuta, near the border with their homeland, Venezuela. Their small home consists of a single room, made from planks of wood.

The family's small home from the outside.

The family's small home from the outside.

Inside, there’s one double bed and a mattress on the floor. In one corner of the room is a bulky old TV that the children use to watch cartoons, and in the other a small stove for cooking.

The family fled to Colombia because Lurexy was promised a job, something that was becoming increasingly scarce in Venezuela. She had to find a way to provide for her children.

“I was able to finish high school. I specialised in chemistry,” says Lurexy with pride.

After finishing school, she began working in the construction sector. But due to the economic crisis in Venezuela, all work dried up.

“Our situation was very difficult,” Lurexy explains. “There was no work. No construction. There was no food. I was pregnant with Luisy. We had to come to Colombia.”

But life in Colombia has been anything but easy.

“They throw rubbish at us”

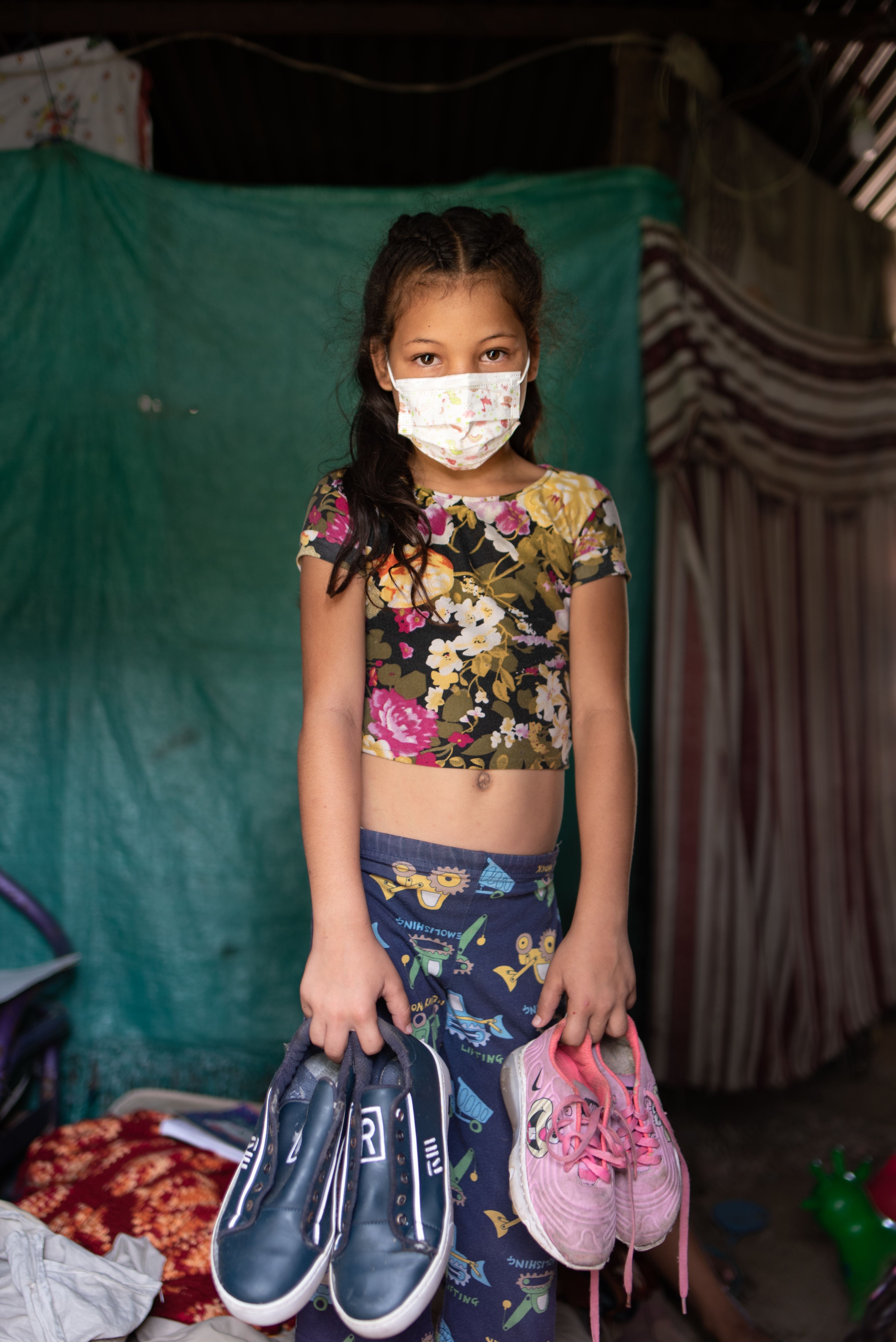

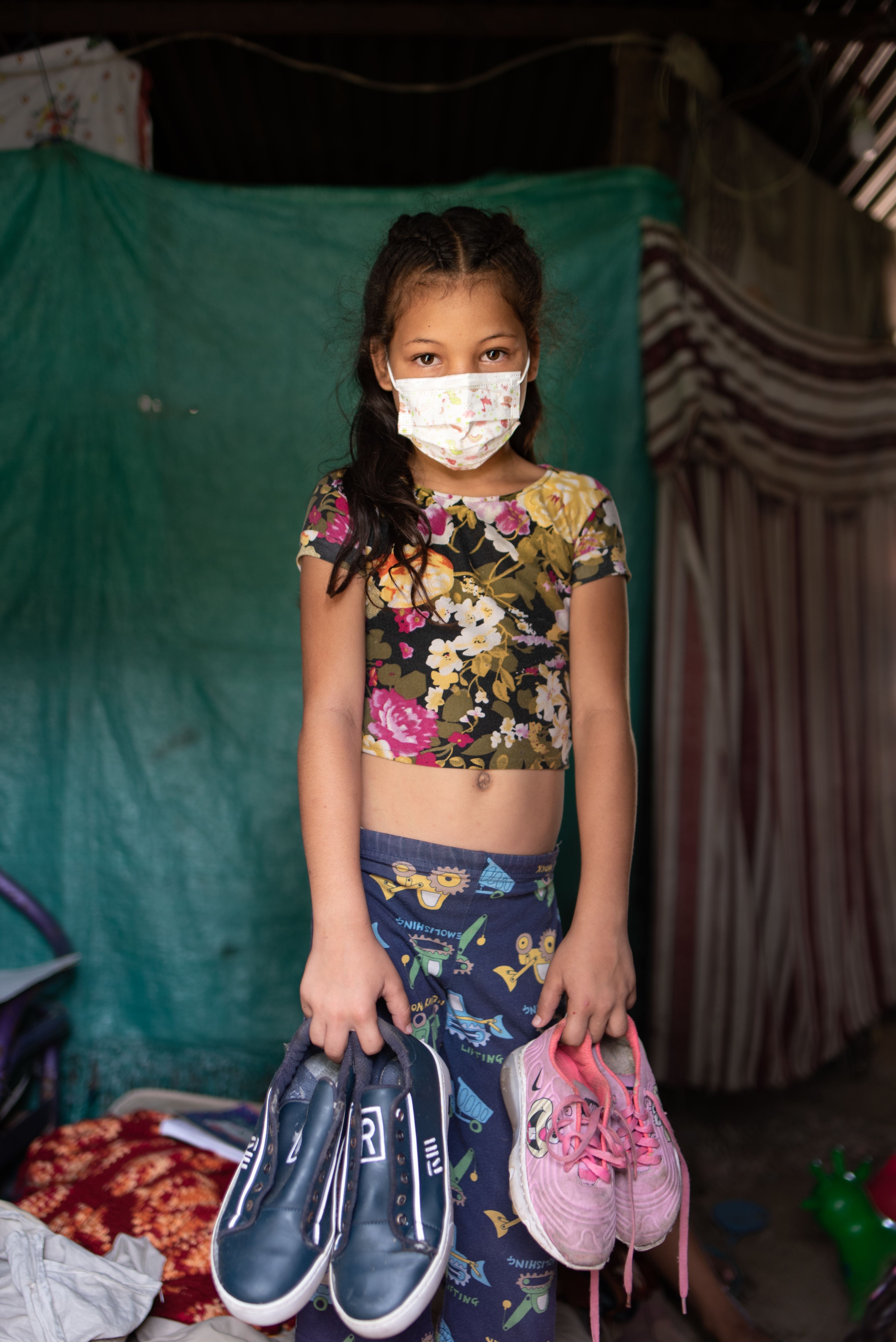

Jesuanny shows off some of the shoes she has collected when helping mum at work. Photo: Christian Jepsen/NRC

Jesuanny shows off some of the shoes she has collected when helping mum at work. Photo: Christian Jepsen/NRC

Lurexy was forced to leave her job in a nightclub when it closed due to Covid-19.

Now, she and her boyfriend Orlfrederick, 25, like many other Venezuelans living in Colombia, make a living from recycling. They walk the streets with a homemade cart in 30C+ heat looking for materials that can be sold.

The children often join in. When it’s time to go to work, the three oldest children grab their caps to protect themselves from the sun and hop onto the cart.

“It hurts so much pushing the cart uphill, especially when it’s full,” says Lurexy.

“But the worst part is the humiliation. People say bad things to us. They throw rubbish at us and call us drug addicts. It feels horrible because it’s often in front of the children.

Jesuanny shows off some of the shoes she has collected when helping mum at work. Photo: Christian Jepsen/NRC

“Jesuanny tells me not to worry. She is strong. She says: ‘mum, don’t be embarrassed, this will enable us to eat’. My children give me hope.”

Venezuelans in Colombia

Over the last six years, the collapse of services and decline in living conditions in Venezuela have prompted one of the biggest mass displacements in the history of South America. More than 5.8 million Venezuelans have left their country.

Millions have fled over the border into neighbouring Colombia. When they arrive, many face a brutal reality of poverty, danger and discrimination.

In February 2020, the Colombian government announced that it would provide temporary protection status to the 1.7 million Venezuelans living within its borders. Although significant progress has been made, this promise has not yet been full realised.

Without official documentation, Venezuelans are forced to live on the fringes, unable to access services or rights.

“Education comes from everywhere”

With the massive influx of Venezuelans in Colombia, the schools have become overwhelmed, and it is very difficult for Venezuelan children to get a place in school.

Jesuanny is now attending school for the first time in five years. Thankfully, due to Lurexy’s determination, she isn’t far behind her peers.

“I am a good mother,” says Lurexy. “Education comes from everywhere. I have been teaching her. She had to do a placement test when she started school and she performed well.”

Lurexy is doing everything she can to ensure her other children don’t fall behind while they’re not in school. They sing songs to remember letters and numbers. And they can often be found colouring and completing activity books at the kitchen table.

“The idea from the beginning was to provide education for my children.”

“Jesuanny helps me to teach the other children. They are good with each other. The oldest two fight sometimes,” Lurexy says as she gives a big sigh, “but they’re good with the little ones.”

“The idea from the beginning was to provide education for my children. The children are smart like their mother,” Lurexy says with a cheeky laugh. “I just hope that they will be able to start to study in a formal school soon to help make all their dreams come true.”

The path to education finally begins

Thanks to funding from the LEGO Foundation, the path to education for Luisy and Jesús has now begun. They’ve started attending an education bridging programme run by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). The programme helps children catch up on the school that they’ve already missed.

Our staff also advocate on behalf of the children so that when they’ve finished the programme, they can secure a place in a state-run school.

The programme is available to children up to the age of 10. Activities focus on developing curiosity, imagination and motivation.

Maryorli Jaimez, 28, is one of Luisy and Jesús’s tutors on the programme.

“The project’s method is to learn by playing,” says Maryorli. “We want children to acquire tools for their first school experience through playing. Tools such as adaptability, compliance with rules, school motivation, and so on.”

A mother’s message

With Jesuanny now in school, and with a new, exciting opportunity beginning for Luisy and Jesús, things are looking more hopeful for the family.

Lurexy is feeling positive about the future.

“My message to all women who have to leave their homes and leave their countries behind, is to go ahead and take their children, because they are the greatest engine that you have as a mother to move forward,” Lurexy concludes.