The world’s most neglected displacement crises in 2020

Millions of children, women and men are trapped in neglected conflicts around the globe today. We do not see them, hear about them or know the horrors they experience. Political inaction is rife, international media attention is sorely lacking and many people are left without any humanitarian assistance to meet their most urgent needs.

Each year, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) publishes a list of the ten most neglected displacement crises in the world, to shine a spotlight on those emergencies that are unseen, unheard and unknown.

This is the list for 2020.

Although humanitarian assistance should be based on needs alone, some crises receive more attention and support than others. This neglect by the international community can be a result of a lack of geopolitical interest. The people affected may seem far away, or the crisis may have lasted for so long that it no longer attracts attention.

Some crises are swept under the carpet for strategic reasons, and countries with the power to improve the situation for the people affected may be unwilling to invest the necessary political capital.

Our aim in publishing this list is to focus on the plight of people whose suffering rarely makes international headlines, who seldom receive high-level visits by donor countries, and who never become the centre of attention for international diplomacy. More information and knowledge about these people’s needs and the crises they endure is an important first step towards improving their lives.

The methodology

The list has been created using three criteria:

- lack of international political will

- lack of media attention

- lack of economic support.

All displacement crises* resulting in more than 200,000 displaced people have been analysed – 40 crises in total.

But what do these criteria mean?

Lack of political will

A qualitative analysis of the international community’s willingness to contribute to political solutions was carried out on all 40 crises. The analysis looked at whether United Nations Security Council resolutions were adopted in 2020; the number and importance of international and government envoys to the conflict; whether the international community engaged in any activities to help establish peace; and whether international summits, donor conferences or high-level meetings were organised. The actions taken were analysed in relation to the size of the displacement crisis.

Lack of media attention

Various factors determine whether a humanitarian crisis receives international media coverage. Even when the media report on a conflict, the humanitarian situation for civilians may be overshadowed by coverage of war strategies, political alliances and fighting between armed groups. So, the level of media attention is not necessarily proportional to the size of the crisis. When developing the list for 2020, media attention towards the different displacement crises was measured using figures from the media monitoring company Meltwater. When comparing media attention, the number of people displaced by each crisis was included in the calculations.

Lack of international aid

Every year, the United Nations and its humanitarian partners launch funding appeals to cover peoples’ basic needs in countries affected by large crises. The extent to which these appeals are met varies greatly. The amount of money raised for each crisis in 2020 was assessed as a percentage of the amount needed, indicating the level of economic support.

*It was not possible to analyse the situation in China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, due to lack of information and reliable figures.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

1. DR CONGO

The mega-crisis engulfing the Democratic Republic of the Congo warranted a mega-response in 2020. Instead, Congolese communities suffered in silence, far from the media limelight and with acutely low international support.

DR Congo’s humanitarian emergency took a downturn in 2020 due to an upsurge in violence and food insecurity. The country became home to the largest number of new internal displacements worldwide, with an average of 6,000 people forced from their homes every single day. Communities fled brutal violence, houses were razed, and families were left without access to basic services like water or healthcare.

In total, more than five million people are currently internally displaced within DR Congo, and an additional million have fled the country, with the majority living as refugees in neighbouring countries.

Humanitarian needs soared

Cyclical violence and displacement left vast amounts of land unfarmed, and people homeless and cut off from their livelihoods. Combined with a slump in the economy and the economic impacts of Covid-19, this meant that hunger levels and humanitarian needs soared. Almost 20 million people were reliant on aid by the end of 2020, compared with some 13 million people the year before. On top of this, the country was affected by two Ebola outbreaks.

Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

Little international support

The gap between humanitarian needs and support was alarming. Less than 33 per cent of the money required to meet the needs of the Congolese people was received, making it one of the world’s most underfunded crises. The stark funding reality in 2020 led the United Nations to appeal for funding to support only 10 million out of the 20 million people in need in 2021.

Decades of conflict have created donor fatigue and a lack of willingness to acknowledge or address the emergencies that are unfolding against a backdrop of a protracted crisis.

Little protection

Donor fatigue was matched by a lack of international political initiatives to bring stability to this African nation. About 100 armed groups were reportedly operating in the eastern parts of the country, wreaking havoc on communities. Despite the presence of UN peacekeepers, the Congolese government and the international community largely failed to protect civilians from being killed, women from being raped by armed men, and children from being recruited by armed groups.

The conflict led to a lack of education opportunities, jeopardising the future of a generation and making children extra vulnerable to violence and recruitment.

2021 brings new record lows

Hunger levels soared further as 2021 arrived, with the United Nations ringing the alarm bell in April that a record 27 million people – one in three Congolese – were suffering from acute hunger.

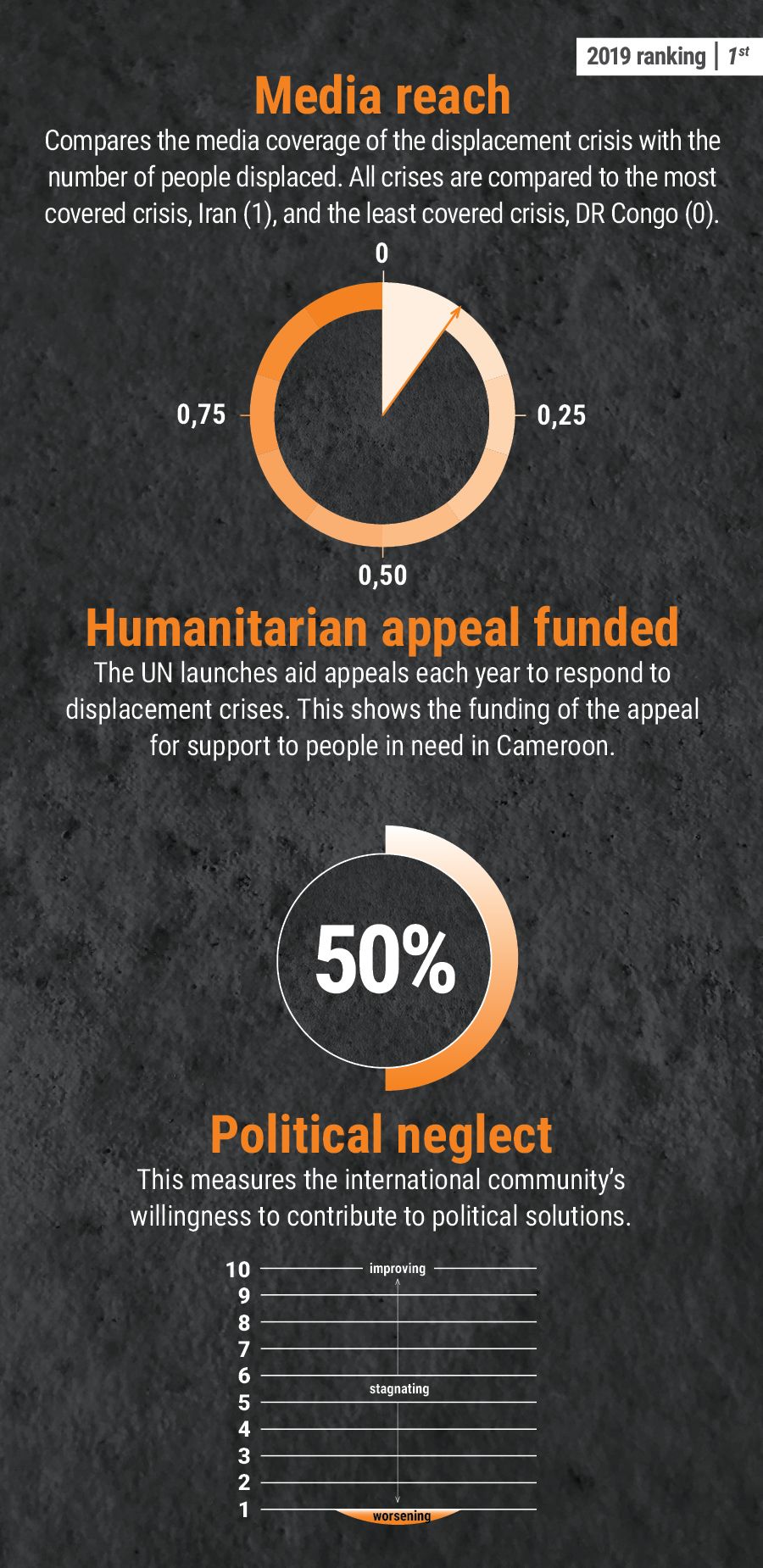

2. CAMEROON

Three separate crises in Cameroon continued unabated in 2020, affecting almost all of the country’s ten regions. Deadly attacks and growing violence triggered massive but underreported numbers of people to flee. The total number of new displacements nearly doubled over the year as an additional 123,000 civilians were uprooted from their homes.

Ongoing violence in the English-speaking parts of Cameroon triggered large-scale displacement, and took a horrific toll on children and their right to education. Some 700,000 children were out of school due to insecurity. An alarming number of attacks on schools and education centres took place as Covid-19 restrictions lifted. Children and their teachers were harassed, kidnapped and killed.

The conflict involving Boko Haram in the country’s Far North region also worsened, forcing more than 300,000 people to flee their homes. Near daily attacks were reported that included killings, kidnappings, theft and the destruction of property.

The country’s refugee crisis continued in the eastern regions, with more than 300,000 Central African refugees still in need of protection.

Cameroon topped our Neglected Displacement Crises list in both 2018 and 2019, largely because of a lack of international attention. A slight rise in aid funding bumped it down from the top spot of this year’s list, but it remained severely neglected.

No successful mediation efforts took place and little international pressure was placed on conflict parties to stop attacking civilians. Media attention was also limited, partly due to a lack of access for journalists to affected areas.

Cameroon’s crisis showed no sign of resolving by early 2021. Attacks on civilians in the Far North region increased sharply and hundreds of homes were looted.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

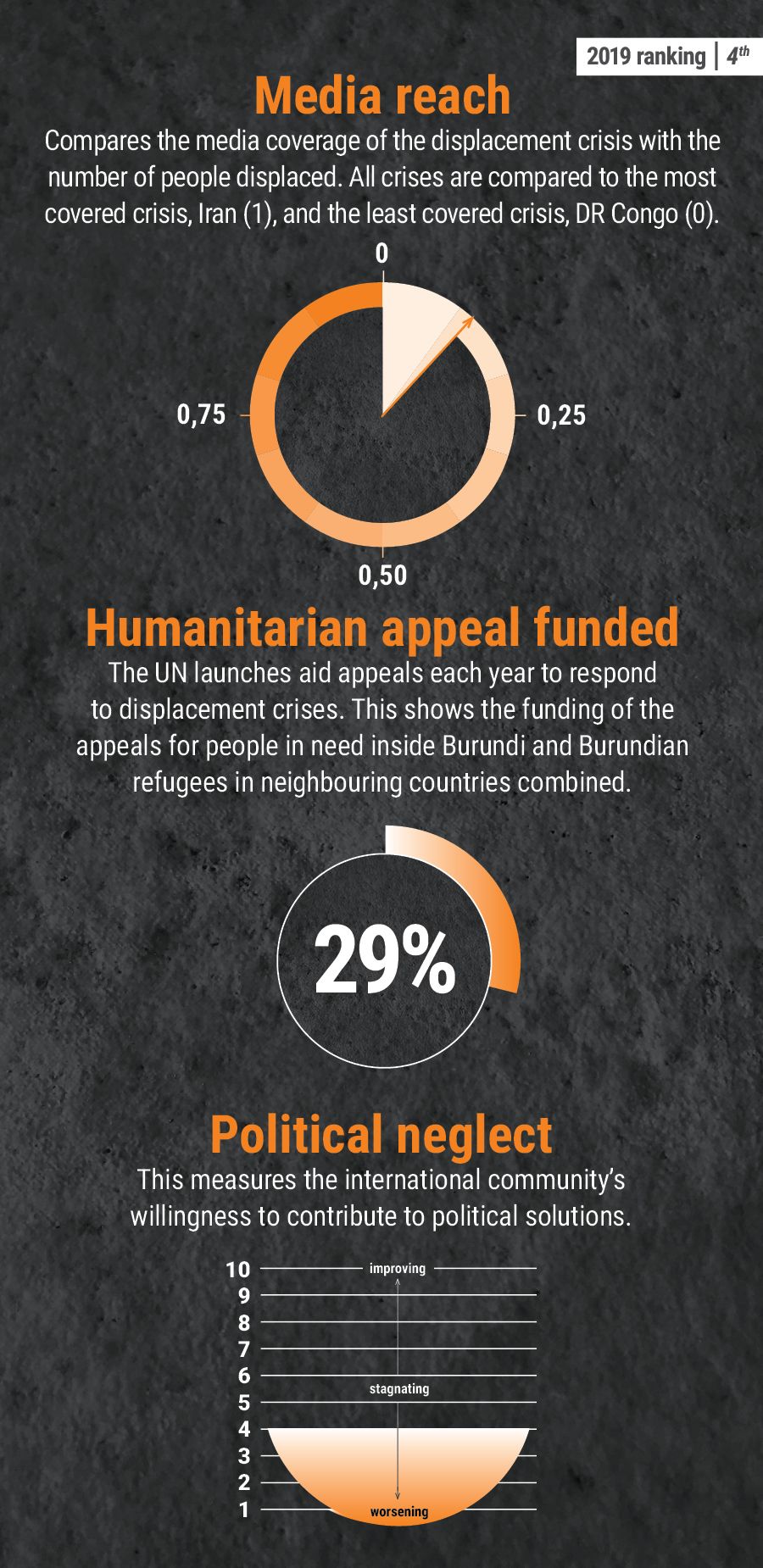

3. BURUNDI

2020 saw Burundi contend with the socio-economic impacts of Covid-19, increased displacement due to climate hazards, and returning refugees, all with limited assistance from the international community.

Following elections and the death of its longstanding president in June, Burundi’s new leader showed tentative signs of reform after years of self-imposed political isolation under the previous president.

However, in September the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi issued warnings about ongoing rights violations and impunity even after the death of the president. The UN Human Rights Council has extended the mandate of the Commission for another year.

The humanitarian funding fell far short. Around 130,000 people were displaced within Burundi by the end of the year, while over 300,000 Burundian refugees were living in neighbouring countries. Yet, the country’s humanitarian response and regional refugee response plans combined were just 29 per cent funded in 2020.

The return of 120,000 Burundian refugees, mainly from Tanzania, also placed a huge strain on already threadbare resources, particularly in urban areas.

While other countries received wide media coverage on climate issues, Burundi’s flooding and drought went virtually unreported, despite accounting for most of its displacement last year.

More flooding is expected throughout 2021. This, along with the loss of economic opportunities from decreased cross-border trade following the pandemic, could increase food insecurity and result in further displacement.

4. VENEZUELA

Venezuelans continued to suffer under the strain of seven years of economic freefall and hyperinflation, and a 2019 political impasse ignited by the opposition-led National Assembly president declaring himself head of state.

The humanitarian emergency showed little sign of abating under the weight of the economic and political crisis. One in three Venezuelans was food insecure by the end of the year, and 30 per cent of all children under 5 years were chronically malnourished.

Over five million Venezuelans have fled the country due to repression and food and medicine shortages since 2014, making it one of the largest displacement crises in the world. While the flow of people out of Venezuela in 2020 was stemmed by pandemic border closures and movement restrictions, the measures raised protection concerns for those refugees and migrants on the move.

Covid-19 exacerbated an already dire humanitarian situation for vulnerable people, with the health system pushed to the brink of collapse and other infectious diseases making a return.

A staggering 10,000 social protests broke out across the country over the year. The majority of protestors took to the streets to decry hardships brought on by the socio-economic fallout from the pandemic.

Venezuela has been on the Neglected Displacement Crises list every year for the last five years, with little international attention given to the emergency. In 2020, the United Nations received less than 40 per cent of the aid funding requested to help Venezuelans in need inside the country and those who had fled to neighbouring nations.

The Organization of American States warned in December that the number of Venezuelan refugees and migrants could rise by two million in 2021, if neighbouring countries reopened their borders and if little changed under the current regime.

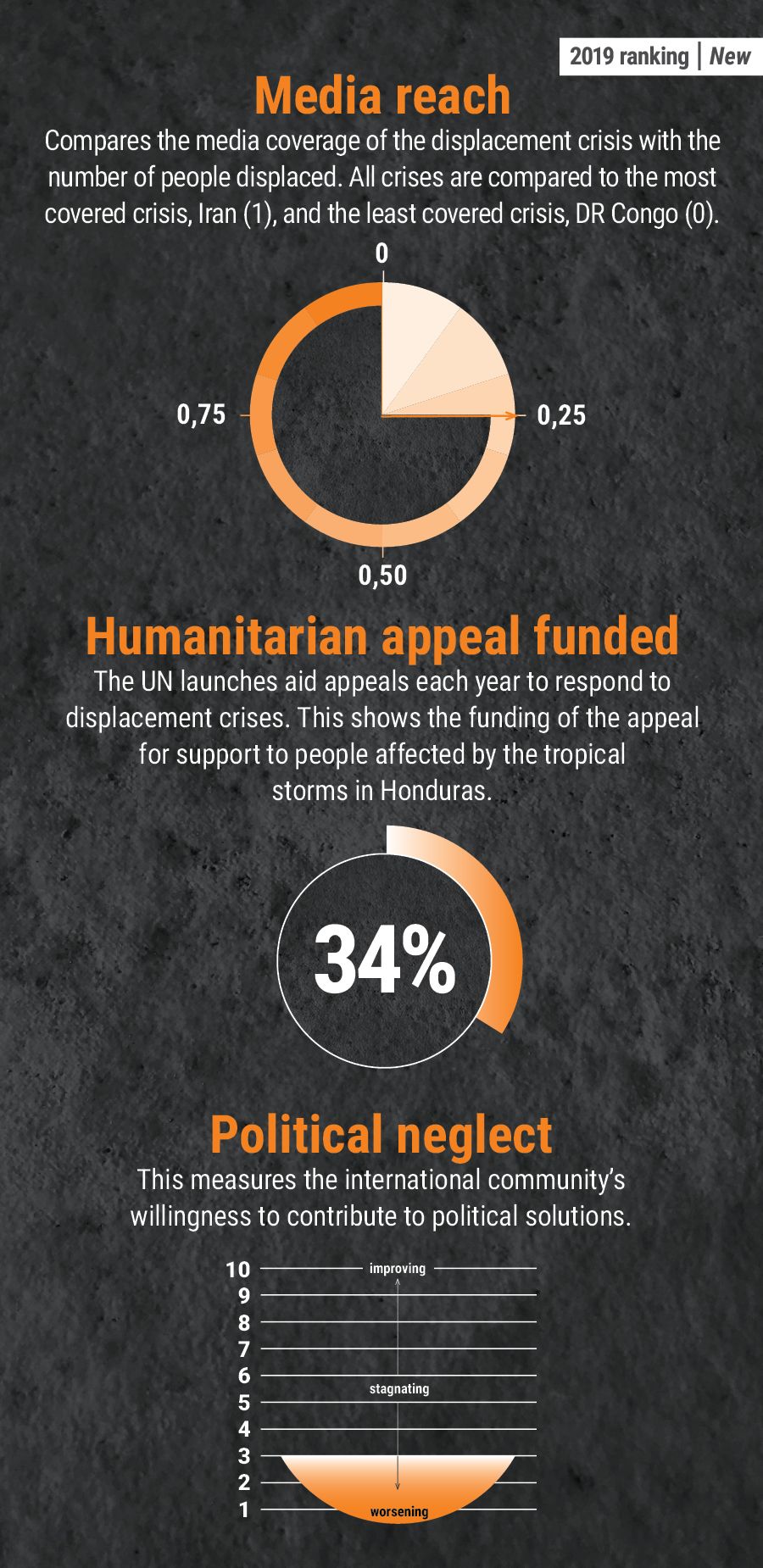

5. HONDURAS

A newcomer to the Neglected Crises list, Honduras was devastated by two tropical storms in 2020. This came on top of years of chronic food insecurity, criminal gang violence, gender-based violence, climate change, and widespread unemployment compounded by the economic consequences of Covid-19.

Tens of thousands of people were displaced by violence or lost hope of a decent life in 2020, and embarked on dangerous journeys in search of safety in Mexico and the United States.

Tropical storms Eta and Iota struck Honduras only two weeks apart in November, affecting close to three million people. Families in the hardest-hit areas scrambled to save personal belongings and seek safety, as relentless mud floods submerged their homes. Many spent several days on roofs awaiting rescue, sharing the little food and water they had.

Despite close to a third of Hondurans being affected by this double disaster, and neighbouring El Salvador and Guatemala also hit hard, the world largely overlooked the deteriorating situation across the North of Central America region. As a result, the aid system failed to provide an adequate coordinated humanitarian response to address needs on the ground.

In 2021, a glimmer of hope was offered to Honduras and its neighbours by the commitment expressed by some powers, including the United States and the United Nations, to promote a regional humanitarian response plan and provide funding.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

6. NIGERIA

The armed conflict in north-east Nigeria showed no sign of ending as it entered its 12th year. Armed violence, restricted movement, and attacks targeting humanitarians are hindering relief organisations from accessing people in need.

More than a million Nigerians received no humanitarian assistance at all, with no access to basic social services, because aid agencies could not safely reach communities affected by the conflict.

Nearly 11 million people were reliant on humanitarian assistance in 2020 as a result of longstanding conflicts, compounded by climate change and the impact of Covid-19. Between 6 and 7 million people faced hunger in the period between harvests – the highest number in four years. Over 3 million Nigerians have been forced from their homes since the conflict started in 2009.

Despite immense needs and a humanitarian space that is shrinking by the day, the international community made few political efforts to address the crisis or the issues preventing humanitarians reaching communities in need. High levels of insecurity and access constraints also contributed to a lack of international headlines on north-east Nigeria in 2020.

The first quarter of 2021 saw the security situation deteriorate even further. A series of attacks on Dikwa and Damasak towns, including humanitarian facilities, led tens of thousands of civilians to flee and forced aid organisations to suspend operations. Access constraints and insecurity also worsened the hunger crisis. The UN warned that some areas of Borno State could slide into famine if the situation continued to worsen.

7. BURKINA FASO

Burkina Faso was the world’s fastest growing humanitarian and protection crisis in 2020, with escalating violence doubling the number of people displaced to exceed the one million mark.

Armed insurgencies, military operations and newly-minted self-defence groups have forced one in every 20 people to flee since 2019. Insecurity has also created ethnic divisions, leading to inter- and intra-community tensions not previously witnessed in the country.

A newcomer to last year’s Neglected Crises list, Burkina Faso’s two-year armed conflict and the economic impacts of Covid-19 have had a heavy impact on civilians. The number of people going hungry nearly tripled over the course of 2020, from over one million to over three million. For the first time in a decade, two provinces were classified at “emergency food insecurity” level.

Children paid a particularly steep price in the violence. Burkina Faso recorded the highest number of attacks against schools in the Central Sahel region, impacting 350,000 students. The abduction and killing of teachers, and the burning and looting of schools, led to more than 2,500 facilities closing their doors during the academic year.

The humanitarian situation in the country garnered little international media attention in 2020, despite massive needs. What sporadic coverage there was revolved heavily around counterterrorism and security issues in the Sahel region, while the country edged quietly closer to a state of protracted crisis going into 2021.

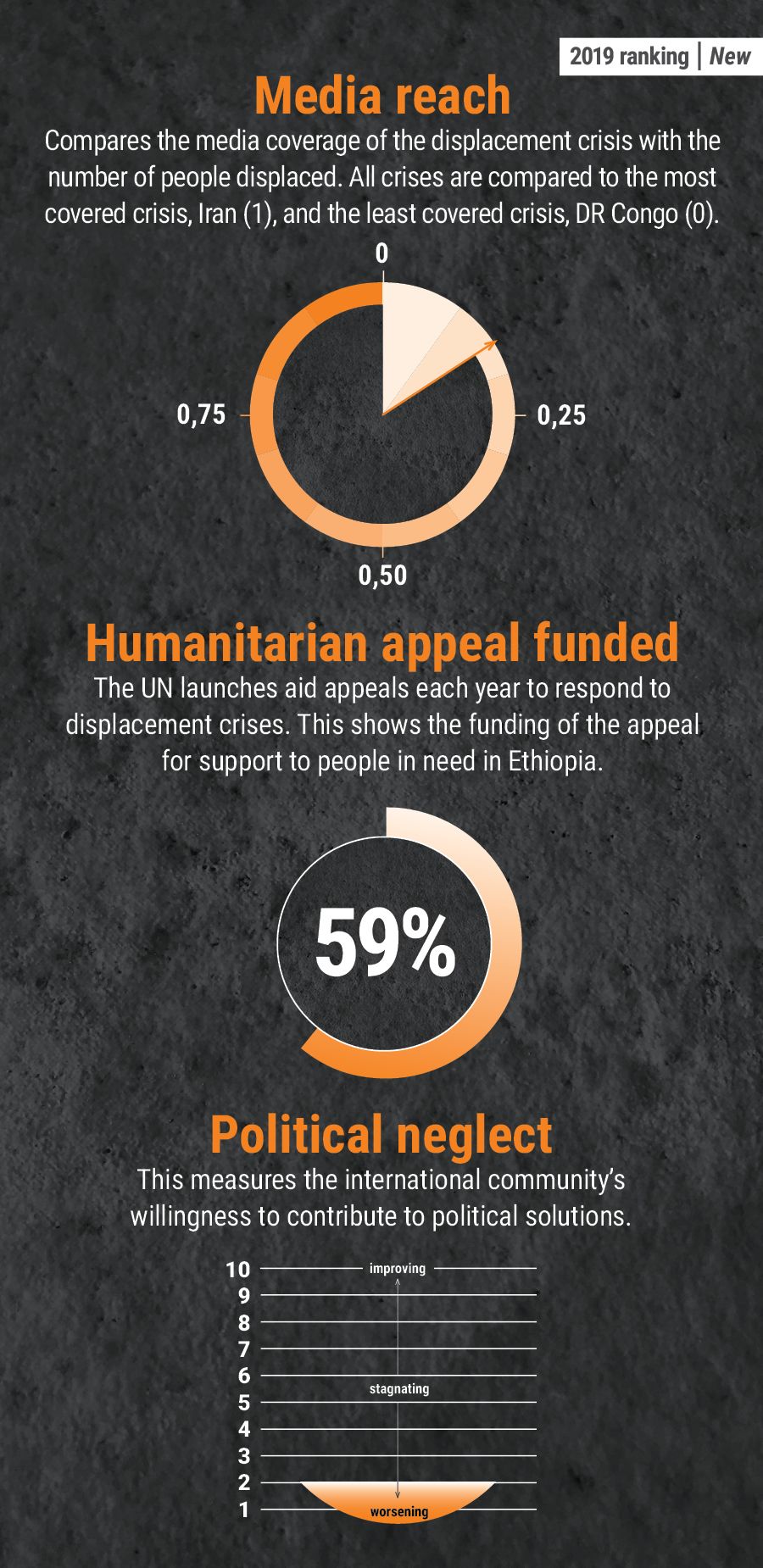

8. ETHIOPIA

A political standoff between Ethiopia’s federal government and regional authorities in the Tigray region escalated into a full-scale conflict in November 2020. Heavy fighting resulted in mass killings, sexual violence, widespread displacement and hunger, with thousands of people seeking refuge in neighbouring Sudan.

Even before the Tigray crisis erupted, Ethiopia was experiencing a severe humanitarian emergency. This was driven by inter-ethnic conflict in other parts of the country, the socio-economic impacts of Covid-19, and climate shocks in the form of drought, flooding and a desert locust invasion.

Ethiopia’s humanitarian response plan was 58 per cent funded in 2020 and failed to match the scale of growing needs, particularly for the 2.7 million people who were internally displaced and the 900,000 refugees from South Sudan, Somalia and Eritrea who were living in the country.

The media briefly turned its attention to Ethiopia to report on the Tigray conflict, but rarely focused on other displacement news and crises in the country up until that point.

Conflict and complicated access conditions in Tigray continued to be a concern into 2021, with no indication that the humanitarian situation would improve in the new year.

However, the election of President Joe Biden saw improved efforts from the US administration to mediate and call for peace in the region. The African Union is also well-positioned to support on mediation efforts in the months ahead, should it choose to step up.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

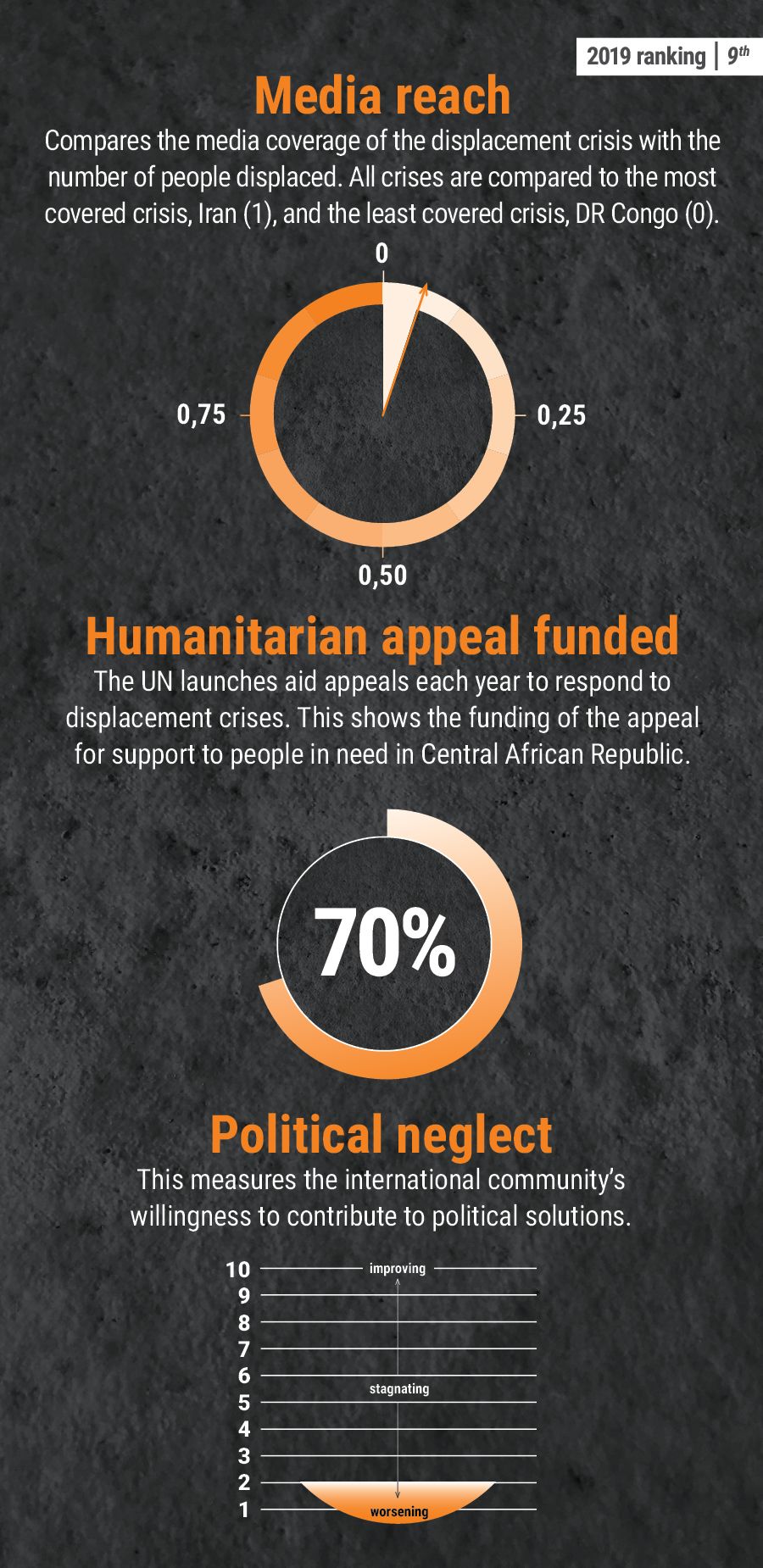

9. Central African Republic

Election unrest at the end of 2020 led to large-scale displacement and an increase in the already extreme humanitarian needs in the Central African Republic.

More than 300,000 people were newly displaced during the course of the year, as a result of a rise in armed group violence, fighting over natural resources and intercommunal fighting.

The rise in violence provided a blow to the 2019 Khartoum peace accords, sponsored by the United Nations and African Union, and revealed the ineffectiveness of the UN peacebuilding efforts undertaken so far to protect civilians.

Some 2.8 million people – more than half of all Central Africans – needed humanitarian assistance in 2020. Despite this, the country’s protracted crisis rarely made international headlines.

While food, primary healthcare and water were the most pressing humanitarian needs, there were also alarming reports of sexual violence against women and girls, and of forced recruitment into armed groups, highlighting the need to better protect civilians.

The humanitarian crisis was relatively well funded. Almost 70 per cent of the requested funds were received by the end of 2020. However, the aid appeal had not anticipated the scale of needs associated with the election violence.

By April 2021, one of the most powerful armed groups committed to quit the coalition of armed opposition groups formed last December with the aim of unseating the president. It reiterated its commitment to the Khartoum peace accords, bringing hope that the accords are not yet dead.

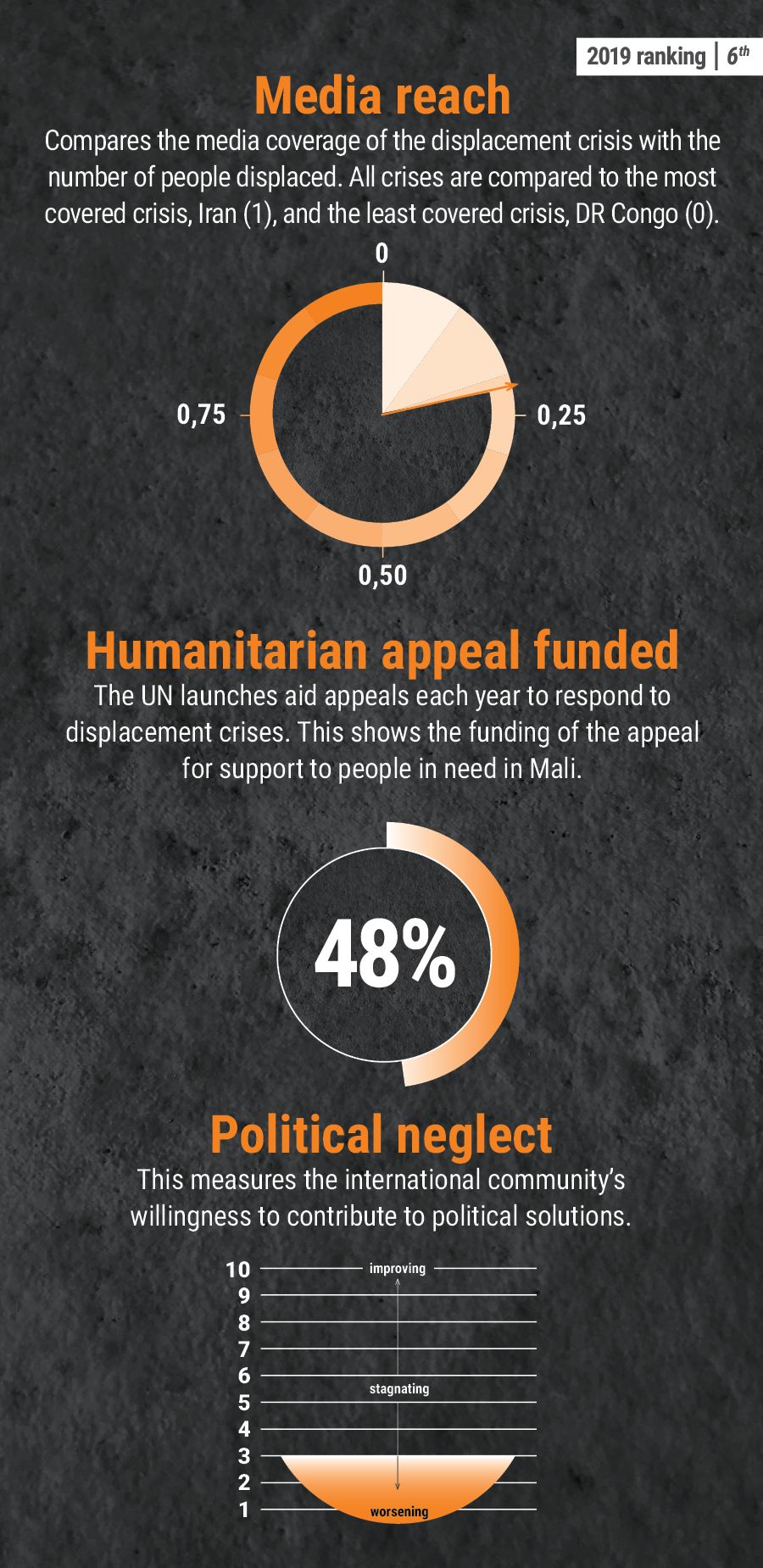

10. Mali

The emergency in Mali has appeared on the Neglected Crises list for the last three years due to severe underfunding of the aid operation, a lack of media attention and a narrow international focus on counterterrorism. These factors remained firmly in place throughout 2020.

The security situation took a downturn as the year progressed, due to violence connected to parliamentary elections, perceived government corruption and a military coup in August.

Insecurity and conflict worsened the overall humanitarian crisis. Some 326,000 people were internally displaced by the end of the year, an increase of over 50 per cent since the end of 2019. Aid agencies struggled to access communities in need due to insecurity and roads that were impassable because of flooding and disrepair. These constraints also limited the media’s ability to report from Mali.

The United Nations, France and some West African nations continued to provide military support to stabilise the country, under the umbrella of counterterrorism operations. But there was no significant improvement in the security situation for civilians as a result of these military efforts. In fact, the militarisation often jeopardised the security of civilians, who were subject to revenge attacks by armed groups expanding in the absence of political leadership.

Humanitarian funding did not keep track with needs, and the aid appeal for 2020 was less than half funded.

The situation looks to stay the same in 2021, with political instability, violent extremism and military operations all continuing alongside the Covid-19 pandemic. Over seven million people are estimated to need humanitarian assistance in 2021, an increase of one million on last year.

Recommendations

While an identical formula will not work for all neglected crises, the recommendations below provide practical steps that particular groups can take to improve the situation for people the international community is currently neglecting.

Politicians and the UN Security Council

- Use your power to push for solutions to neglected conflicts, to ensure respect for international law, and to tackle humanitarian access constraints.

- Ensure that counterterrorism policies do not negatively impact the ability of humanitarians to reach communities in need.

- Promote press freedom to ensure journalists working in crisis-affected countries can continue to report on humanitarian emergencies.

Donors

- Urgently provide increased humanitarian funding to neglected crises, and support action to prevent famine that is threatening the lives of 34 million people, many living in neglected crisis contexts.

- Increase flexible and predictable aid funding in line with the commitments of the Grand Bargain initiative, so that the money is used effectively to support communities who need it, when they need it.

- Provide humanitarian assistance according to the needs of people affected by crises, and not according to geopolitical interests or levels of media interest.

- Prioritise underfunded aid sectors, including education in emergencies and protection.

- Increase the ability of humanitarians to work in hard-to-reach areas by improving risk-sharing among different actors. Humanitarians are needed most in places where armed groups operate and where governance is weak. But too few NGOs are present in the hardest-to-reach areas. Donors must be willing to provide sufficient funding to manage risks.

- Ensure additional resources are raised in response to needs arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, rather than diverting existing funding from the humanitarian response.

Humanitarian actors

- Prioritise neglected crises when applying flexible funding.

- Ensure timely, accurate and coordinated humanitarian response plans that fully reflect the immense needs in neglected crises. Ensure the appeals are not adjusted downwards for crises where the available funding is expected to be limited.

- Improve coordination between aid organisations on the ground. Optimise the use of resources and avoid unnecessary competition for the limited resources available.

- Invest in advocacy. Often countries that receive the least funding cannot afford advocacy and communication resources, creating a vicious circle and making it difficult to lift these crises out of neglect.

Journalists and editors

- Invest in quality journalism from underreported crises. Continue to look for new angles and untold stories from protracted crises, and report in a way that focuses on solutions and does not contribute to exacerbating conflicts.

- If reporting is hindered by red tape, such as lack of media permissions or visas, use media platforms to advocate for the necessary changes, and explore digital solutions to get first-hand accounts from people on the ground.

- Engage in efforts to protect press freedom, to ensure domestic and international journalists working in crisis-affected countries can continue to report.

The public

- Read up about neglected crises and support quality journalism that covers forgotten conflicts.

- Speak up about neglected crises, for example by activism on social media, and in your community and networks.

- Check what political candidates and parties say about refugees, humanitarian crises and foreign policy before voting. Ask politicians about these crises and push for them to take political action.

- When providing economic support to a crisis, avoid earmarking support to the crises that receive most media attention, as this may not necessarily be where your support is most needed. Consider making a regular donation.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.