The world’s

most neglected

displacement crises

in 2019

Every day millions of children, women and men are trapped in forgotten conflicts in far corners of the world. Political inaction is rife and international media attention is sorely lacking. As a result, humanitarian support is often insufficient to meet peoples’ needs. Too often, countless families are left to fend for themselves.

Each year, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) publishes the list of the ten most neglected displacement crises in the world, to shine a spotlight on these forgotten emergencies.

This is the list for 2019.

Although humanitarian assistance should be based on needs alone, some crises receive more attention and support than others. This neglect can be a result of a lack of geopolitical interest. Or the people affected may seem too far away for many to identify with. Neglect can also be the result of the lack of willingness to compromise by parties to political conflicts, creating protracted crises and growing donor fatigue.

The aim in publishing this list is to focus on the plight of people whose suffering rarely makes international headlines. More information and knowledge about these people and the crises surrounding them is a first important step towards improving their lives.

The methodology

The list has been created based on three criteria: lack of political will, lack of media attention and lack of economic support. All displacement crises* resulting in more than 200,000 displaced people have been analysed – 41 crises in total.

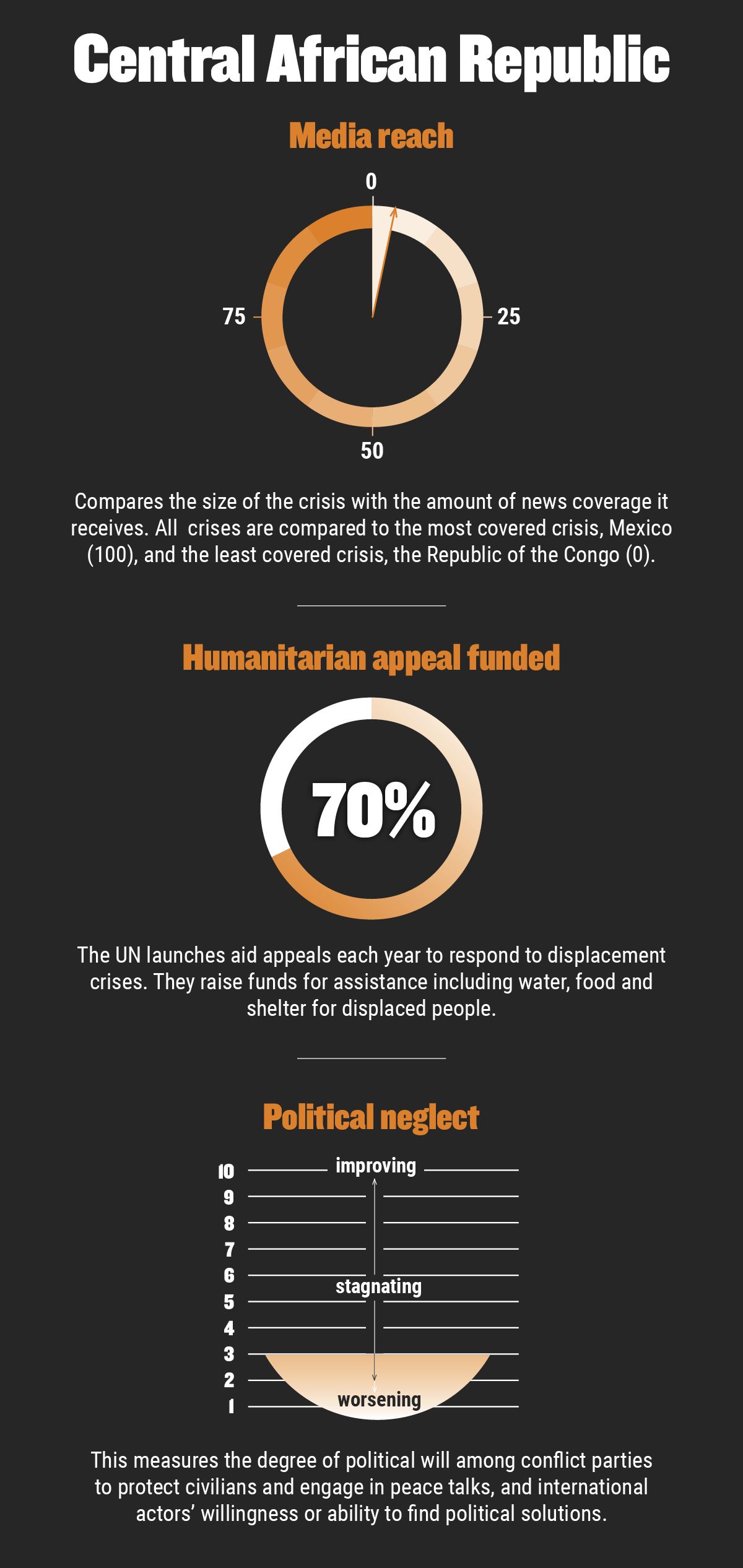

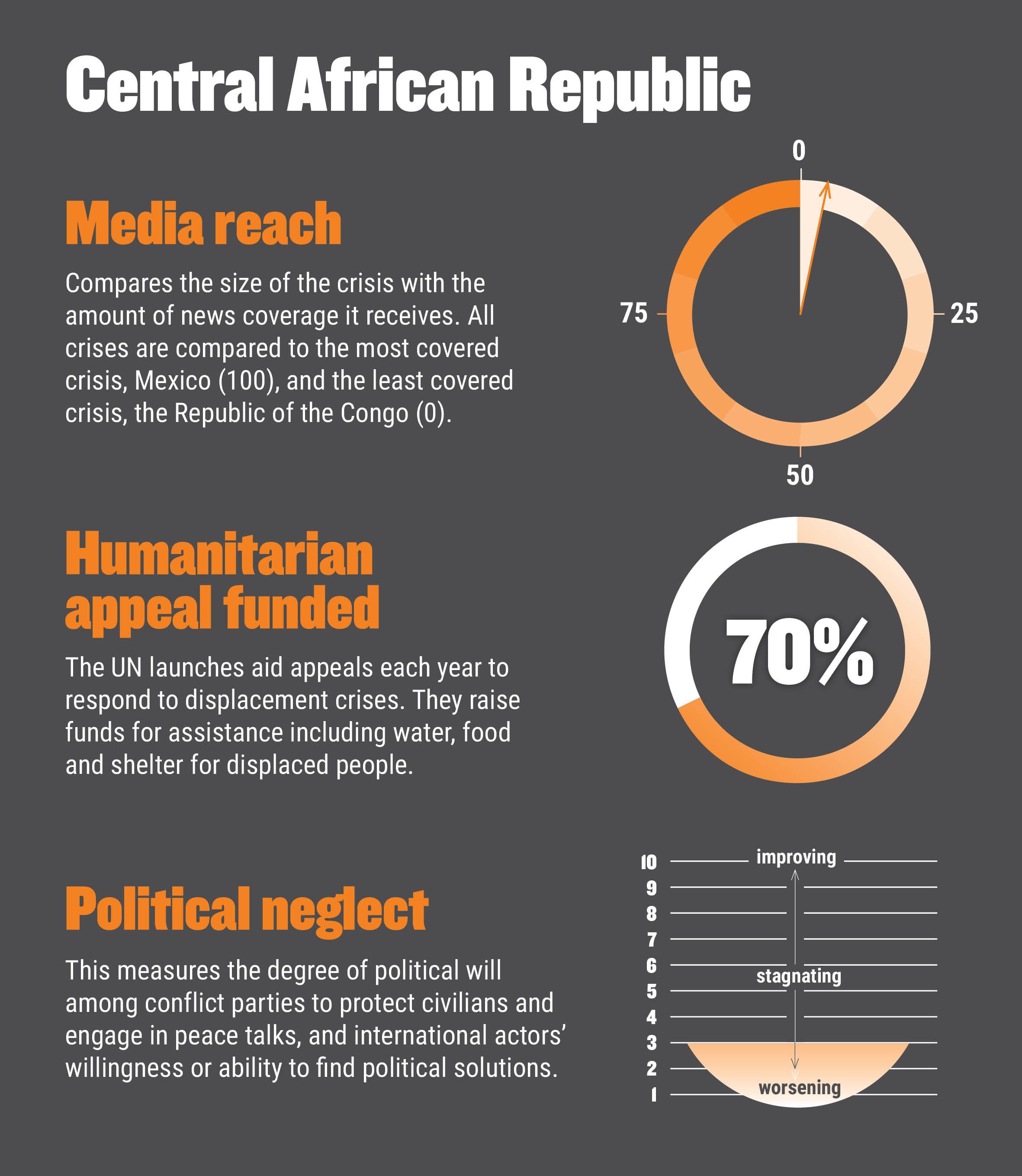

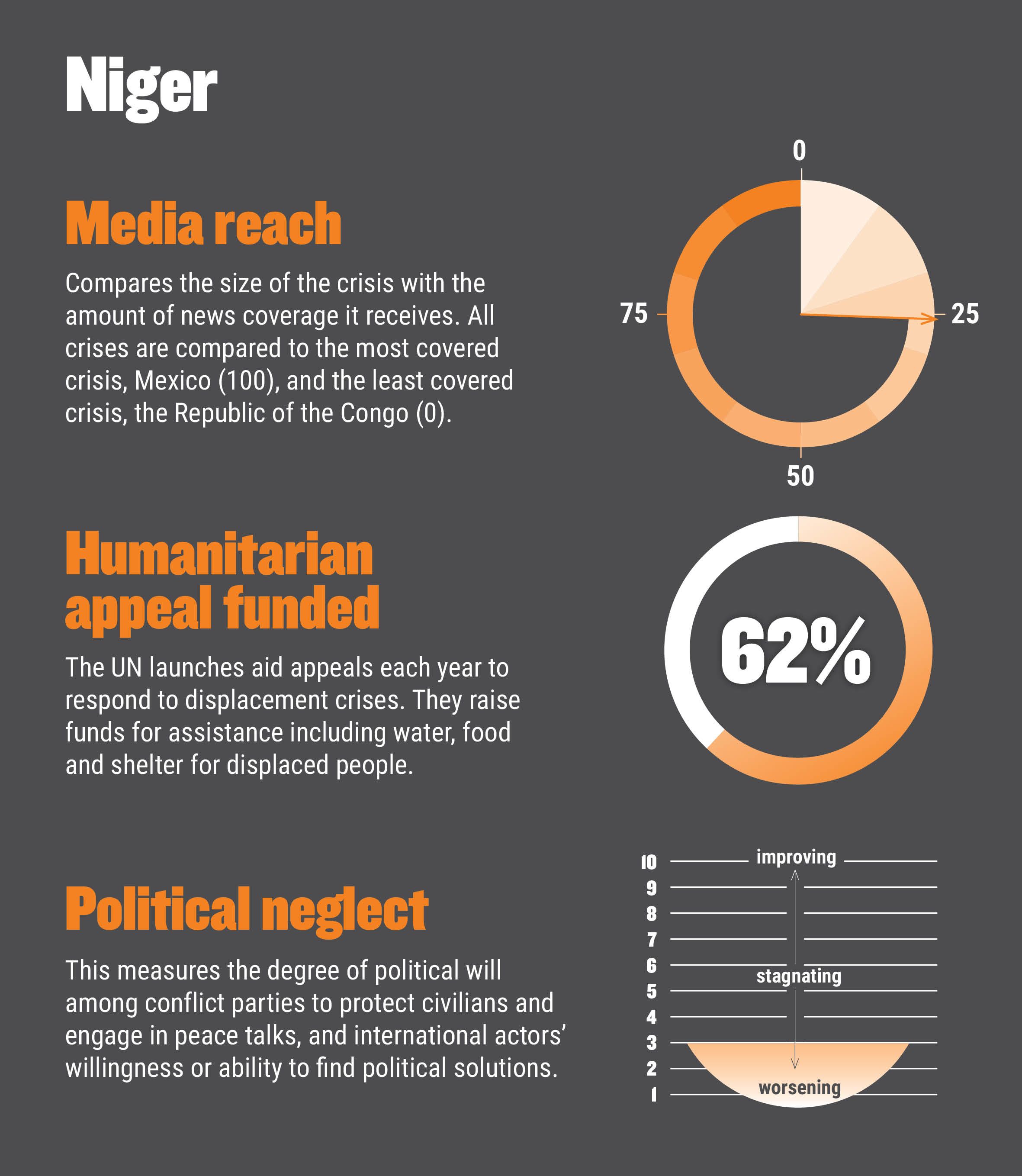

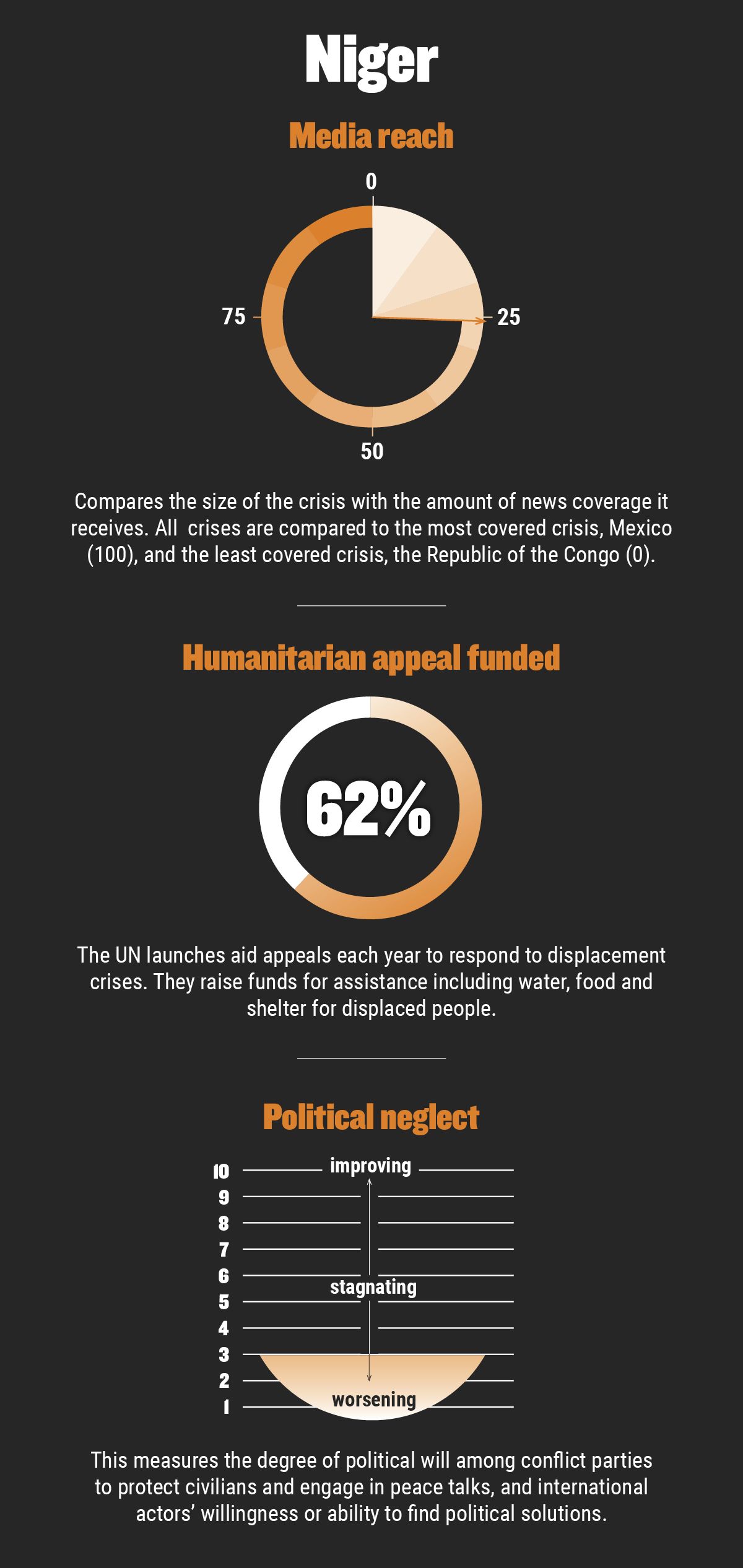

Lack of political will. This includes both the degree of political will among armed parties on the ground to protect the rights of civilians and engage in peace negotiations, and the international community's willingness or ability to find political solutions.

The existence of a peace process, a decrease in the number of displaced people, and other positive developments are used to determine the level of political will. The lack of such processes, a deterioration of the situation for civilians, and increased displacement indicate the opposite.

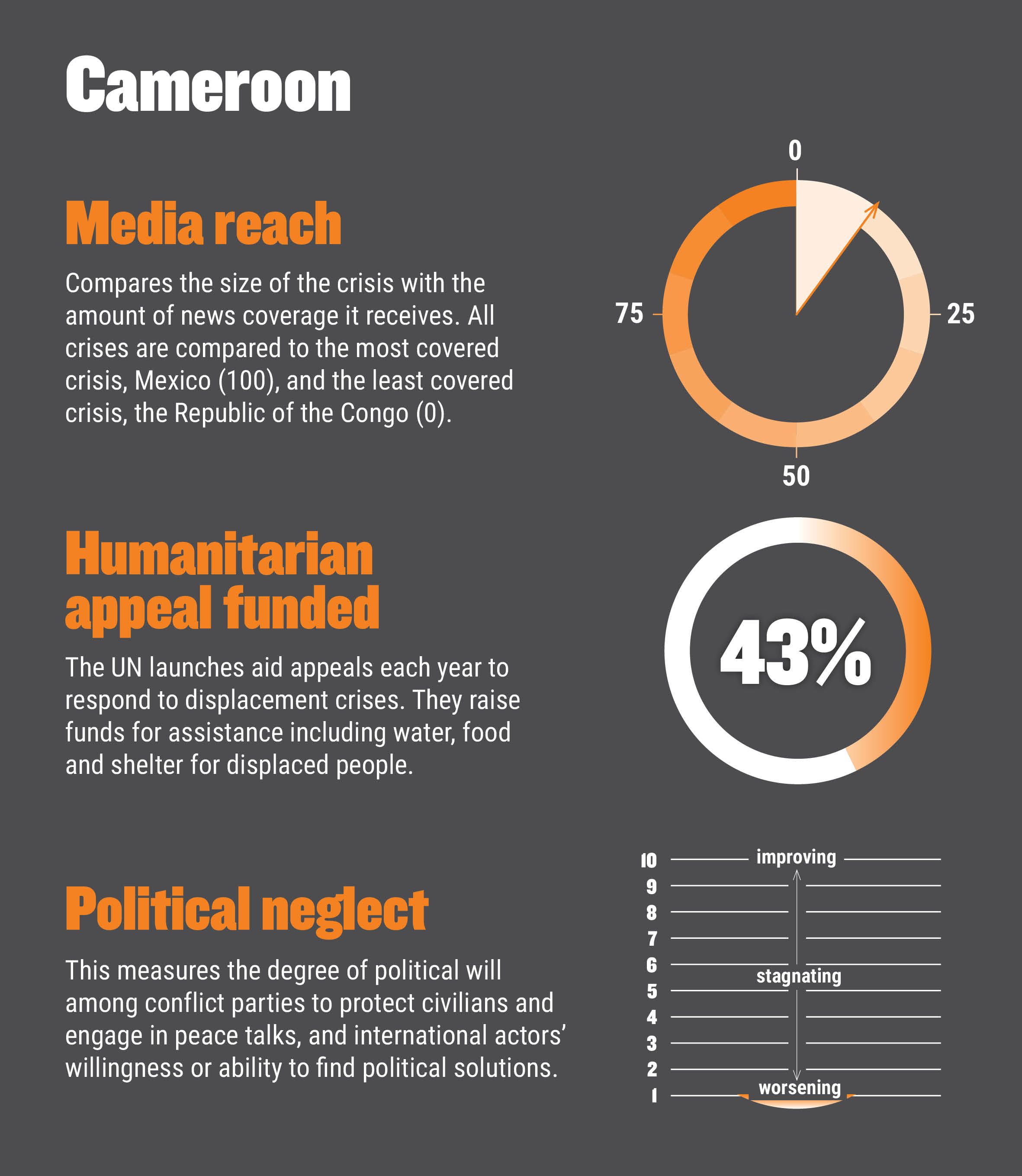

Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

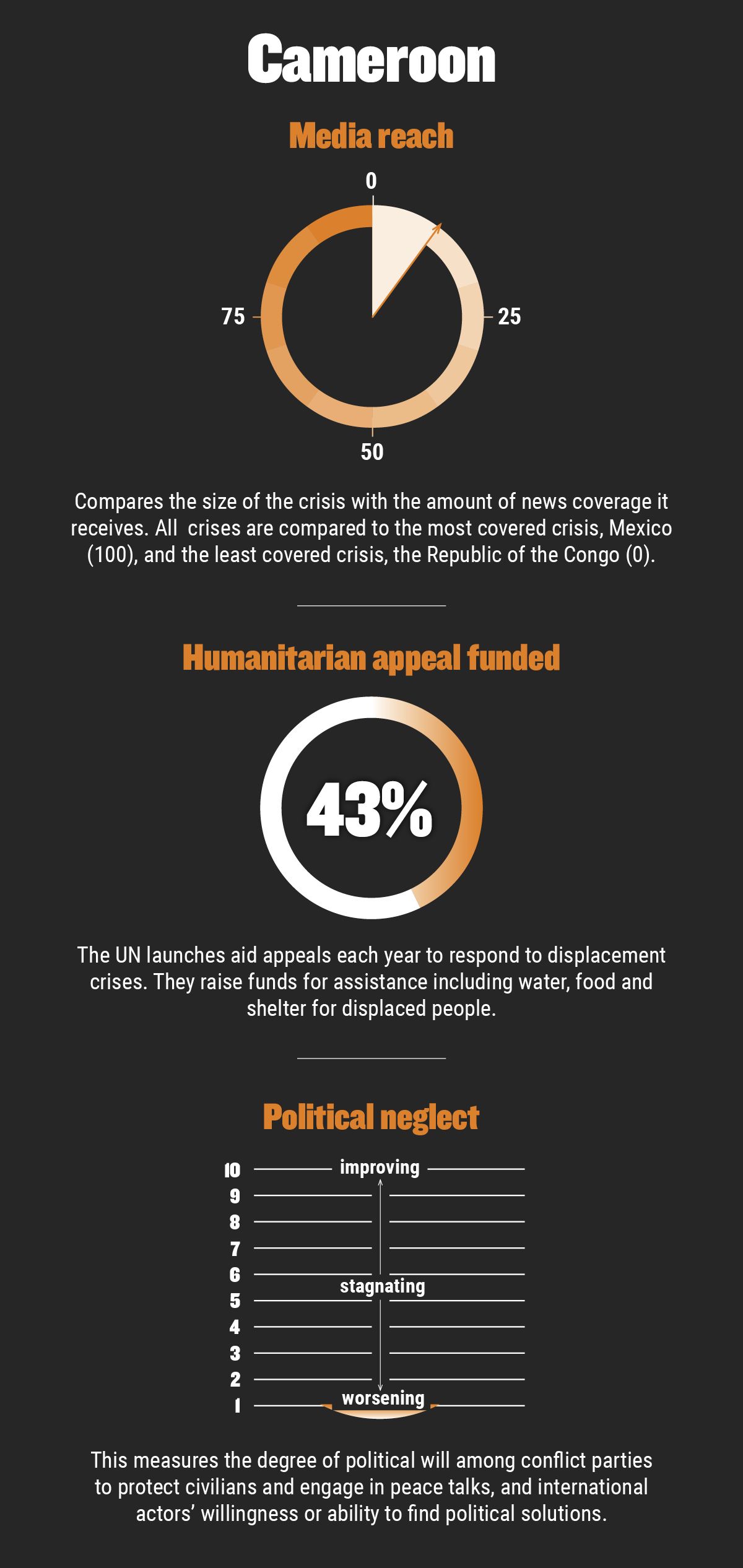

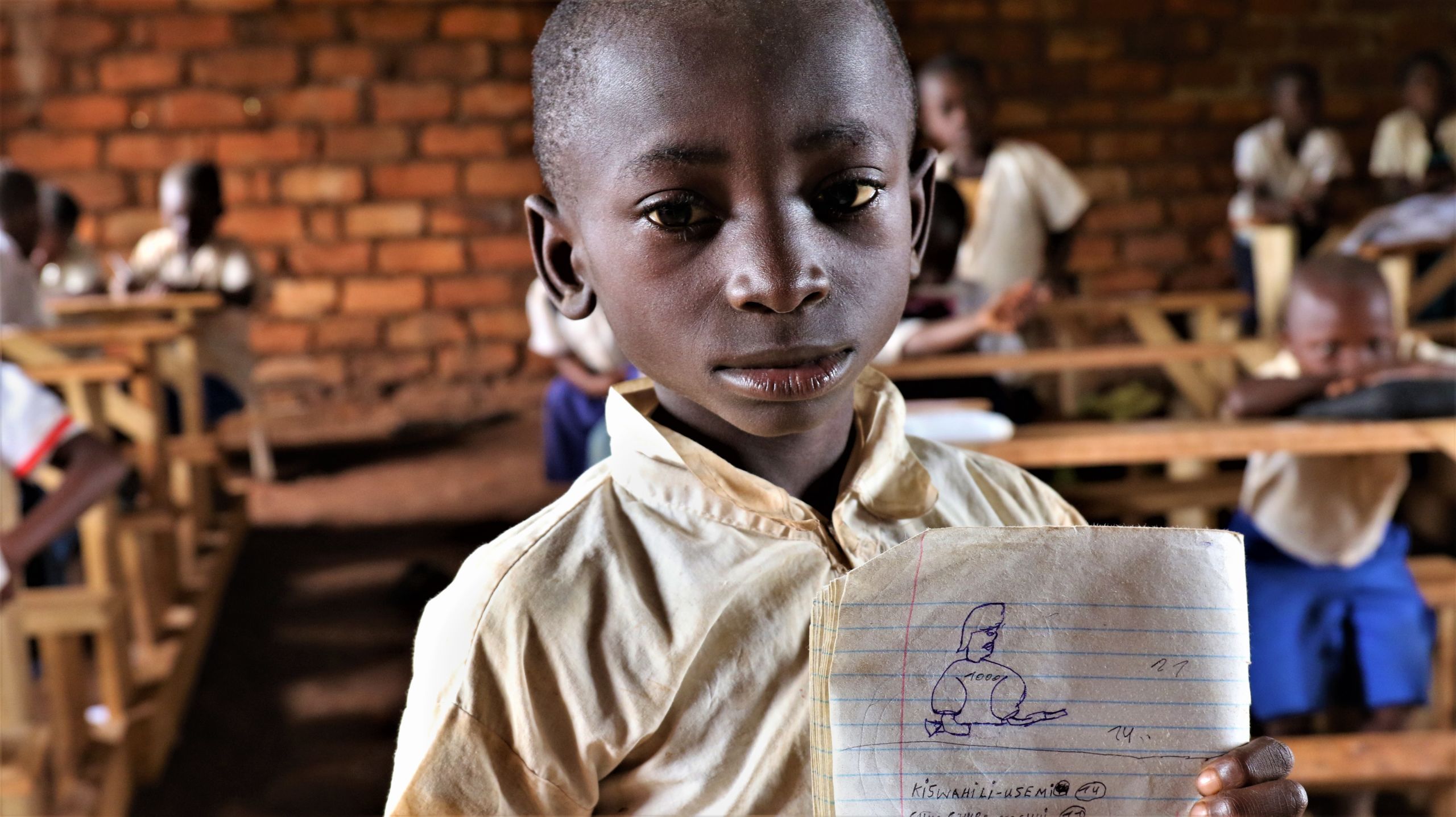

Lack of media attention. Various factors determine whether a crisis receives international media coverage. Even when the media report on a conflict, the humanitarian situation for civilians may be overshadowed by coverage of war strategies, political alliances and fighting between armed groups. So the level of media attention is not necessarily proportional to the size of the crisis. When developing our list for 2019, we measured media attention using figures from media monitoring company Meltwater. When comparing media attention, we also included the size of every displacement crisis in the calculations.

Lack of international aid. Every year, the United Nations and its humanitarian partners launch funding appeals to cover people’s basic needs in countries affected by large crises. But the extent to which these appeals are met varies greatly. We used the percentage that each appeal was covered in 2019 to indicate levels of economic support.

Read last year’s list here.

*Due to lack of information and reliable figures, we have been unable to analyse the situation in China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

1. Cameroon

2018 ranking: 1st

Mounting violence, political paralysis and an aid funding vacuum contributed to Cameroon topping the list of the world’s most neglected crises for a second year running.

Three separate crises continued to pound Cameroon in 2019: an exacerbation of Boko Haram attacks in the Far North region, a political crisis in the North-West and South-West regions, and a refugee crisis in the eastern part of the country.

Hotbed of hostilities

The Far North became a hotbed of hostilities due to conflict between the armed group Boko Haram and government forces. The former carried out over 100 attacks in the region over the course of the year, killing more than 100 civilians. By the end of 2019, close to half a million people had been forced to flee. Violence increased hunger levels, wiped out livelihoods and destroyed infrastructure.

Complex humanitarian emergency Tensions in the English-speaking North-West and South-West regions turned violent in 2017, spawning a humanitarian emergency which intensified during 2019.

Government forces carried out large-scale offensives and armed groups retaliated. Civilians were trapped in the middle. Over 3,000 people have been killed in the violence since the crisis began in 2016. Unlawful killings, torture and razing of villages were widely reported by human rights groups.

The crisis has displaced nearly 700,000 people within the country since it began, while another 52,000 have fled to neighbouring Nigeria for safety. The North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon were already suffering from poverty prior to the crisis, and 80 per cent of all health and education services were not functioning.

A national dialogue was held to address the crisis in September 2019, resulting in the regions being given a special status, and hundreds of political prisoners being released.

Refugee crisis

A total of 280,000 refugees had fled to Cameroon from the Central African Republic by the end of 2019. A tripartite agreement between the two countries and the UN Refugee Agency set up in June only succeeded in assisting about 3,000 people to return home by the end of the year. Prospects for large-scale return looked unlikely entering into 2020.

Out of the spotlight

Despite Cameroon struggling to respond to three separate crises, it rarely made the headlines, garnering little international media attention. Reporters Without Borders ranked it 134th out of 180 countries in its World Press Freedom Index, and reported frequent arbitrary detention and prosecution of journalists. Few international journalists gained access to the conflict areas. This likely contributed to the lack of media coverage of the country.

Cameroon was also one of the lowest funded international humanitarian appeals in the world, with donors showing little appetite to help the struggling African nation. Only 43 per cent of the appeal had been funded by the end of the year.

2019 was another year devoid of successful mediation and saw little pressure on conflict parties to stop attacking civilians.

The first quarter of 2020 failed to see the violence ease, with armed group attacks forcing close to 8,000 people to flee the Far North in March and April alone.

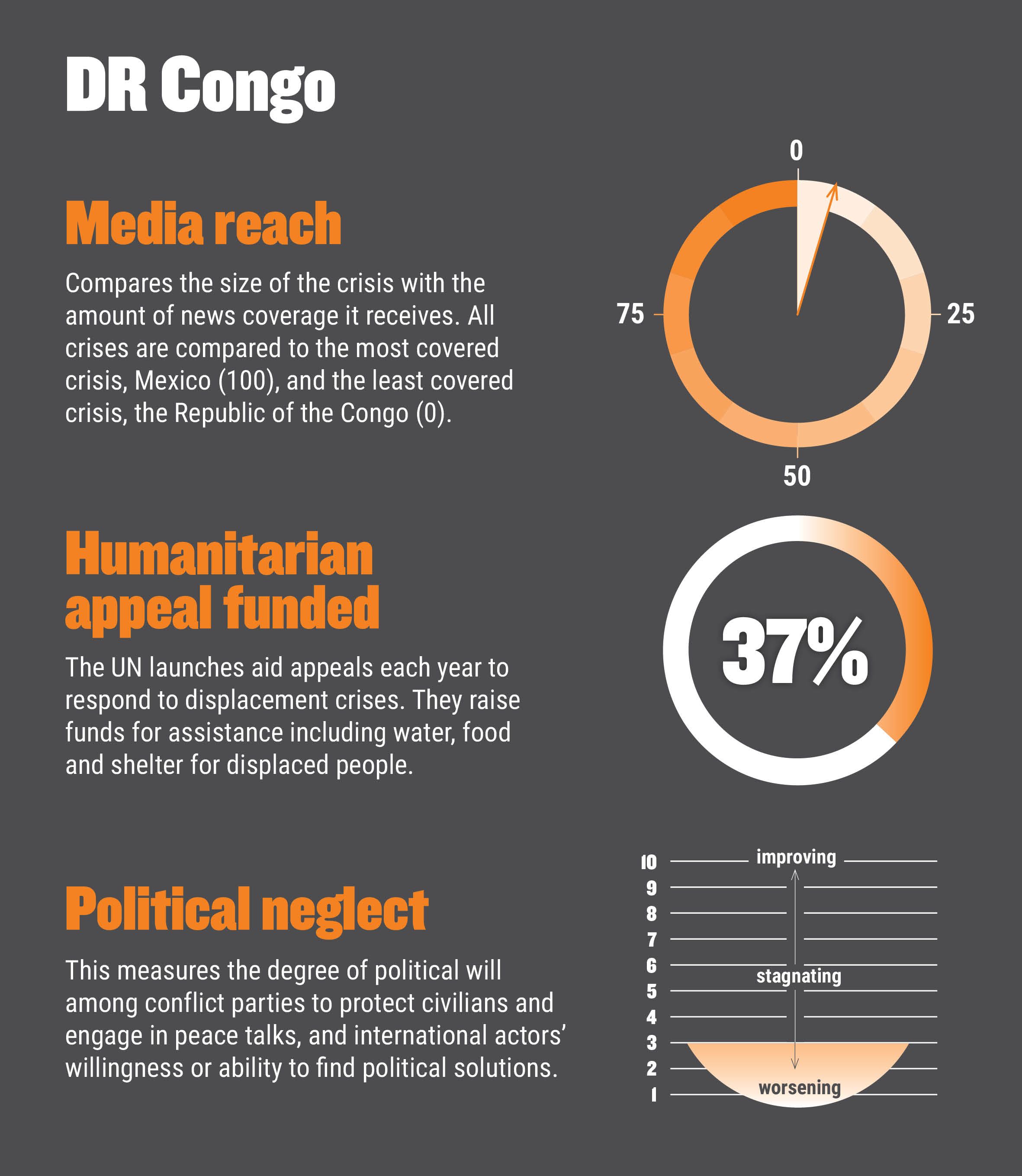

2. DR Congo

2018 ranking: 2nd

The political calm after the change of president in late 2018 brought a semblance of hope to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo). This optimism was sadly short-lived, as atrocities and conflict in 2019 left many Congolese living in fear of brutal attacks in the eastern part of the country.

Violence pushed almost 1.7 million people to flee their homes, the highest number of newly displaced people of any country in Africa. Military operations, armed group attacks and upsurges in intercommunal fighting forced hundreds of thousands of Congolese to flee in the eastern provinces of Ituri, South Kivu and North Kivu.

DR Congo was the second largest hunger crisis in the world after Yemen in 2019. The number of people unable to feed themselves stood at over 15 million. On top of that, almost four million children under the age of five were acutely malnourished.

The Congolese faced multiple challenges in 2019. An outbreak of the Ebola virus in Ituri and North Kivu provinces killed over 2,200 people during the year.

The outbreak was the second largest in the world, and the largest in DR Congo’s history. The country also experienced its worst measles epidemic in modern times. At least 209,000 people were infected between January and October, and more than 4,100 died. Flooding severely affected over 900,000 people in the north. Despite being the world’s second biggest internal displacement crisis after Syria, international attention and donor funding fell badly short. By the end of the year, donors had contributed less than half of the money needed to help over 10 million people, making it one of the lowest funded appeals globally.

Fighting in early 2020 brought the total number of people forced from their homes in the Ituri region to over one million since 2018.

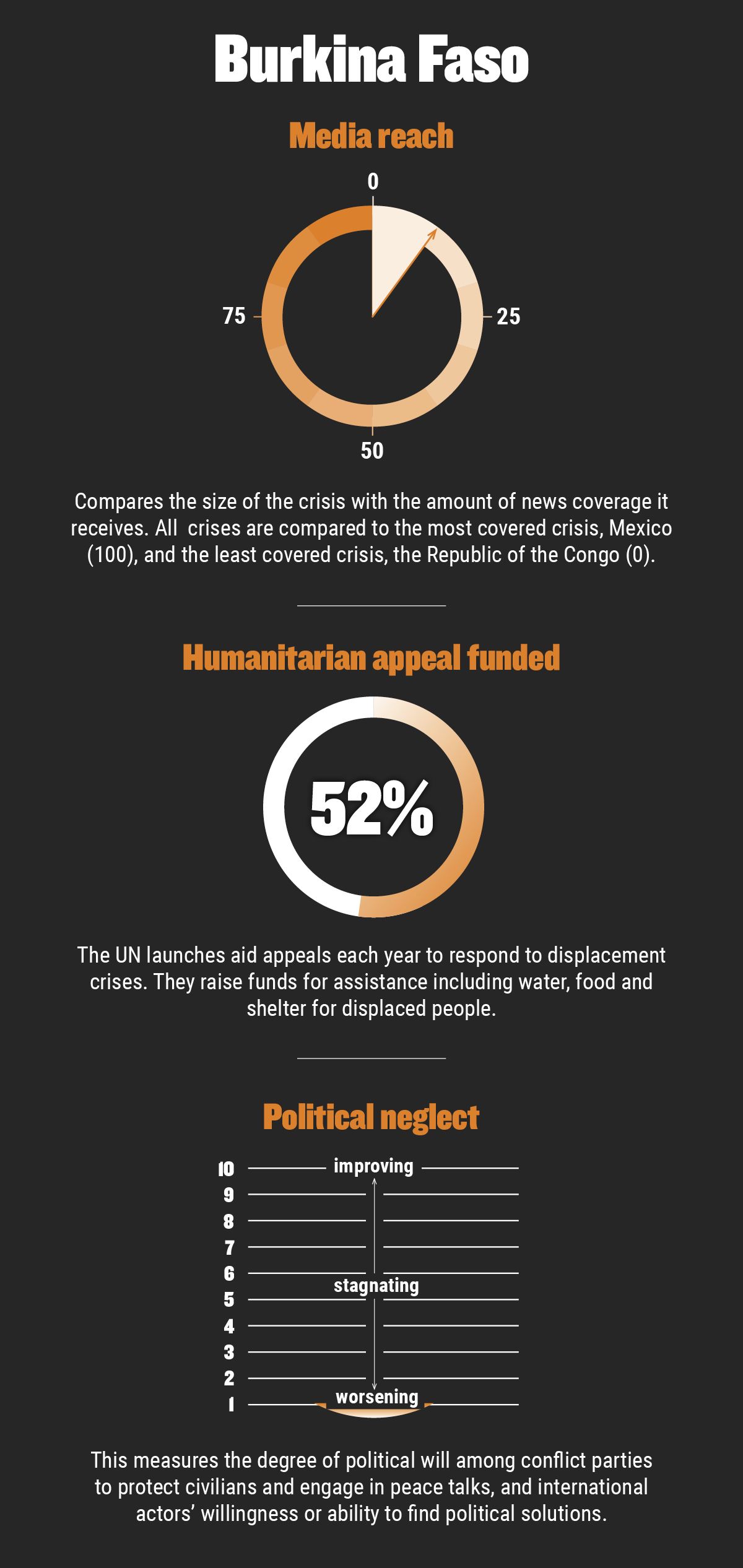

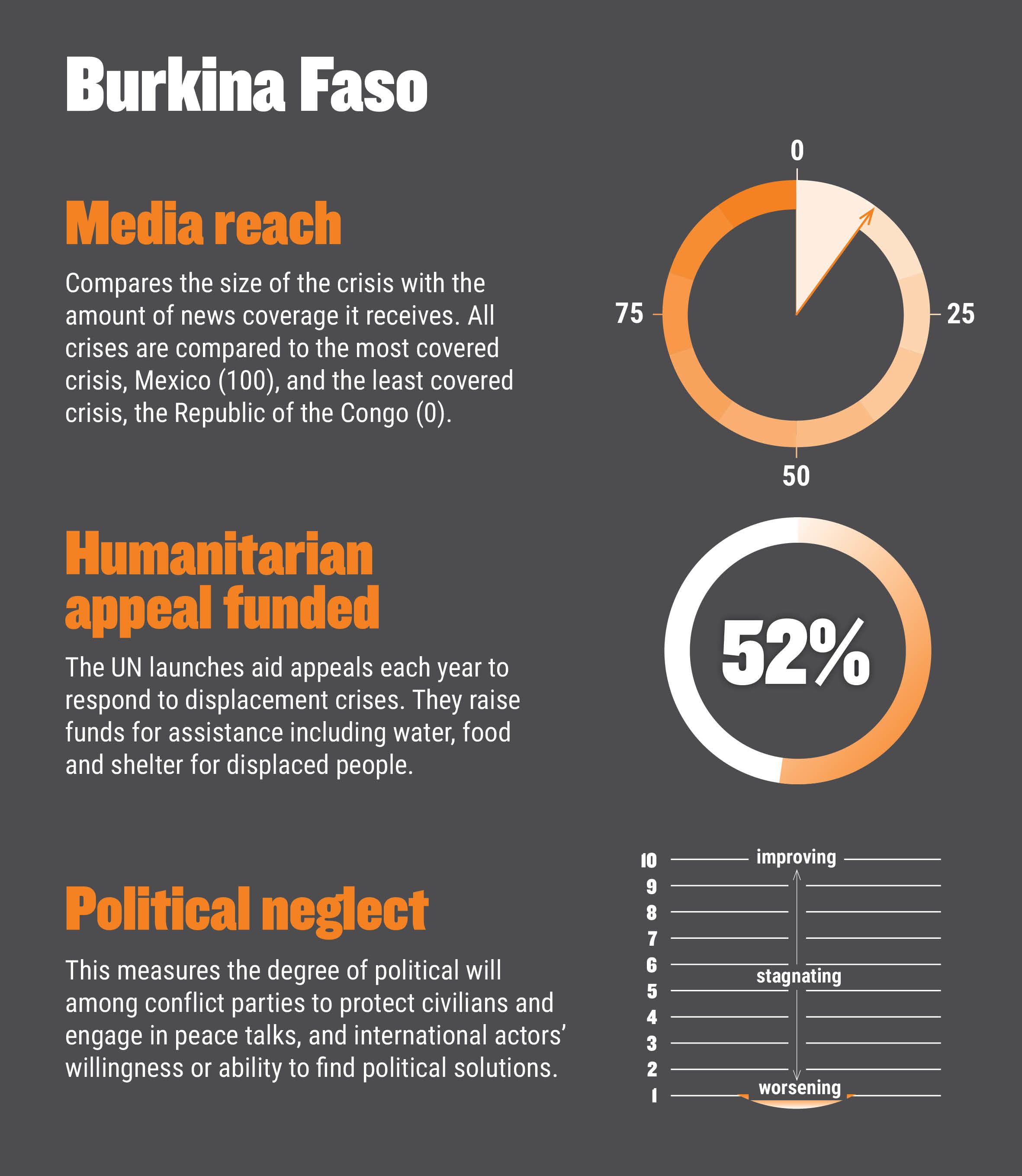

3. Burkina Faso

2018 ranking: New

Burkina Faso is a newcomer to this year’s Neglected Crisis list. It was the world’s fastest growing displacement crisis in 2019, with a fivefold increase in internally displaced people to nearly 500,000.

Violence in northern Mali spilled into Burkina Faso in 2018, igniting insecurity that engulfed large swathes of the country. The government stepped down in January 2019 after months of attacks by armed groups. Fighting continued unabated despite a new government forming.

Civilians were caught in the crossfire between armed group violence and government-led military operations. The violence also created ethnic divisions that led to intercommunal and terrorist attacks not witnessed previously in Burkina Faso. These attacks and crossfire with government forces led to a fivefold increase in the number of people forced to flee. Some 2,200 people lost their lives.

Hunger levels also rose sharply, with over 1.2 million people needing food assistance by the end of 2019.

Many displaced people fled from farmland their families had owned for generations, unable to harvest their crops – in a country where four out of five people rely on farming for their livelihoods. A lack of property documents made it uncertain whether they would be able to continue using the same farmland if and when they returned home in the future.

Despite spiralling humanitarian needs, only half of the money required by the United Nations and aid groups to help those in need was raised.

These factors saw Burkina Faso enter 2020 in a precarious position. Food insecurity forecasts deteriorated even further, with a tripling of the population in severe food insecurity.

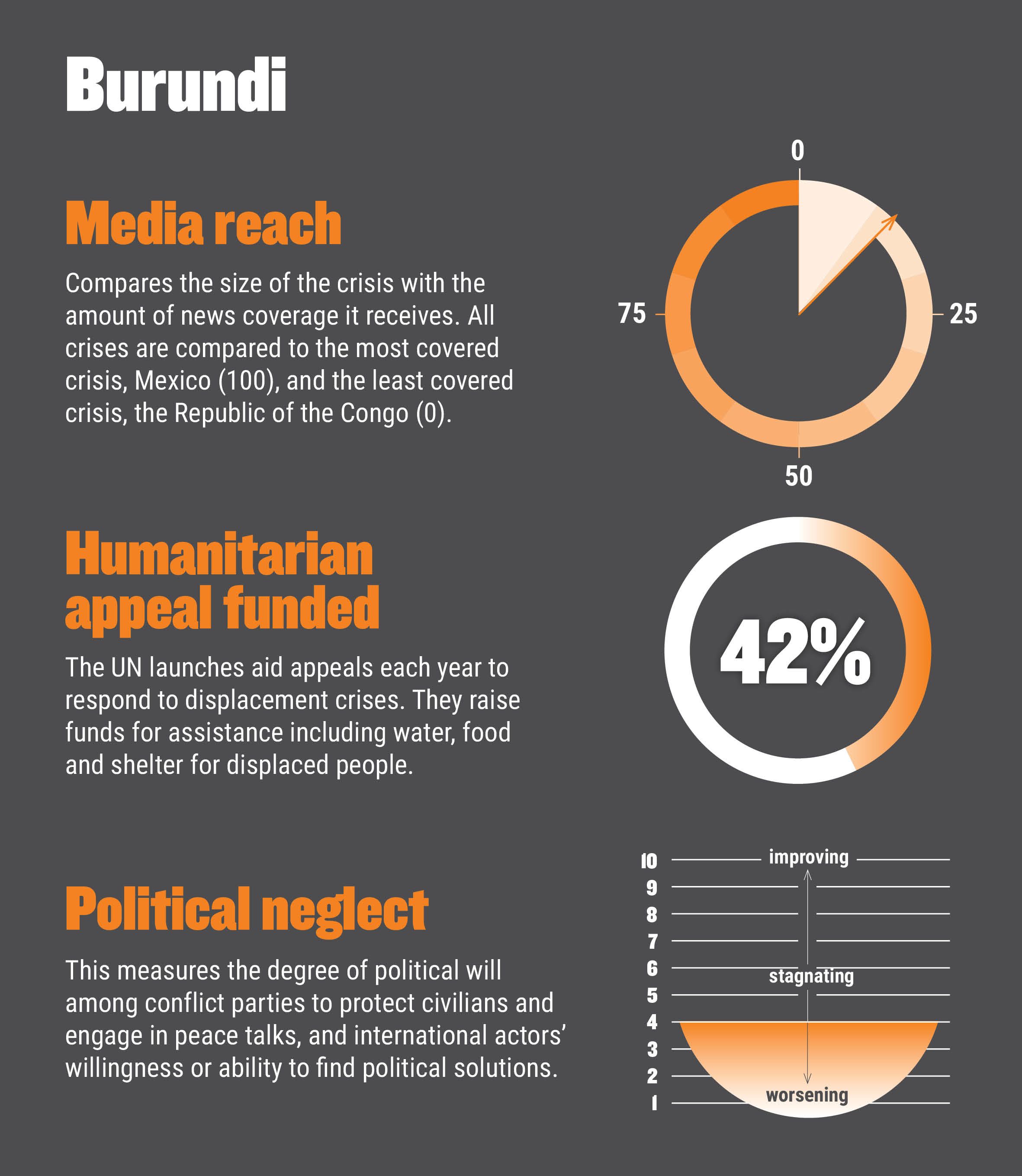

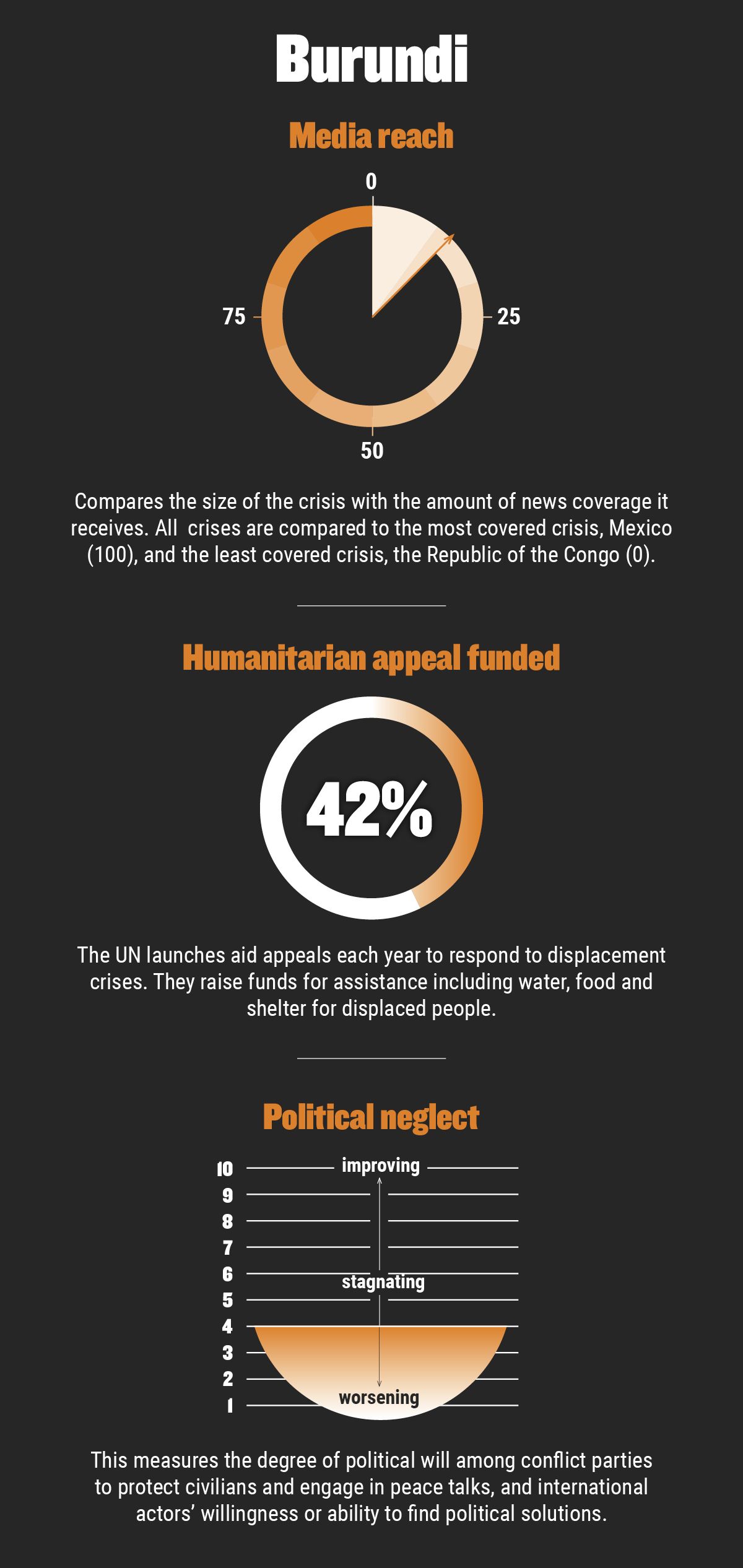

4. Burundi

2018 ranking: 4th

There were fewer visible manifestations of unrest in Burundi in 2019 compared to 2015, when President Pierre Nkurunziza decided to pursue a third electoral term, triggering months of protests, a failed coup and widespread violence that displaced thousands. However, the East African country’s political and humanitarian crises were far from over in 2019.

Burundians still faced considerable political and economic pressure, and continued to witness violence on the streets. Human rights groups reported that citizens suspected of being supporters of the political opposition were often arrested, beaten or killed. The government was accused of clamping down on critics and the media. Few international journalists were granted entry into the country, which likely contributed to the low media coverage of the crisis.

The prolonged political crisis had a negative impact on the country’s socio-economic situation. Burundi’s economy continued to flounder as a result of declining investment, a shortage of foreign exchange reserves, price inflation and limited aid. The humanitarian appeals to help Burundians were only 42 per cent funded at the end of the year.

Malaria was one of the leading causes of infant mortality and child malnutrition during 2019. An epidemic infected eight million of the country’s 11 million people, with over 3,100 people dying – far higher than the numbers of Ebola deaths in neighbouring DR Congo – but this catastrophic health issue received little international attention.

Some 333,000 Burundians, many of whom had fled the political unrest of 2015, lived in exile in neighbouring countries.

Despite nearly 80,000 people returning voluntarily to Burundi by the end of 2019, between 500 and 1,000 were still fleeing the country each month to seek asylum elsewhere, either because of fears for their safety or because of the impact of economic collapse.

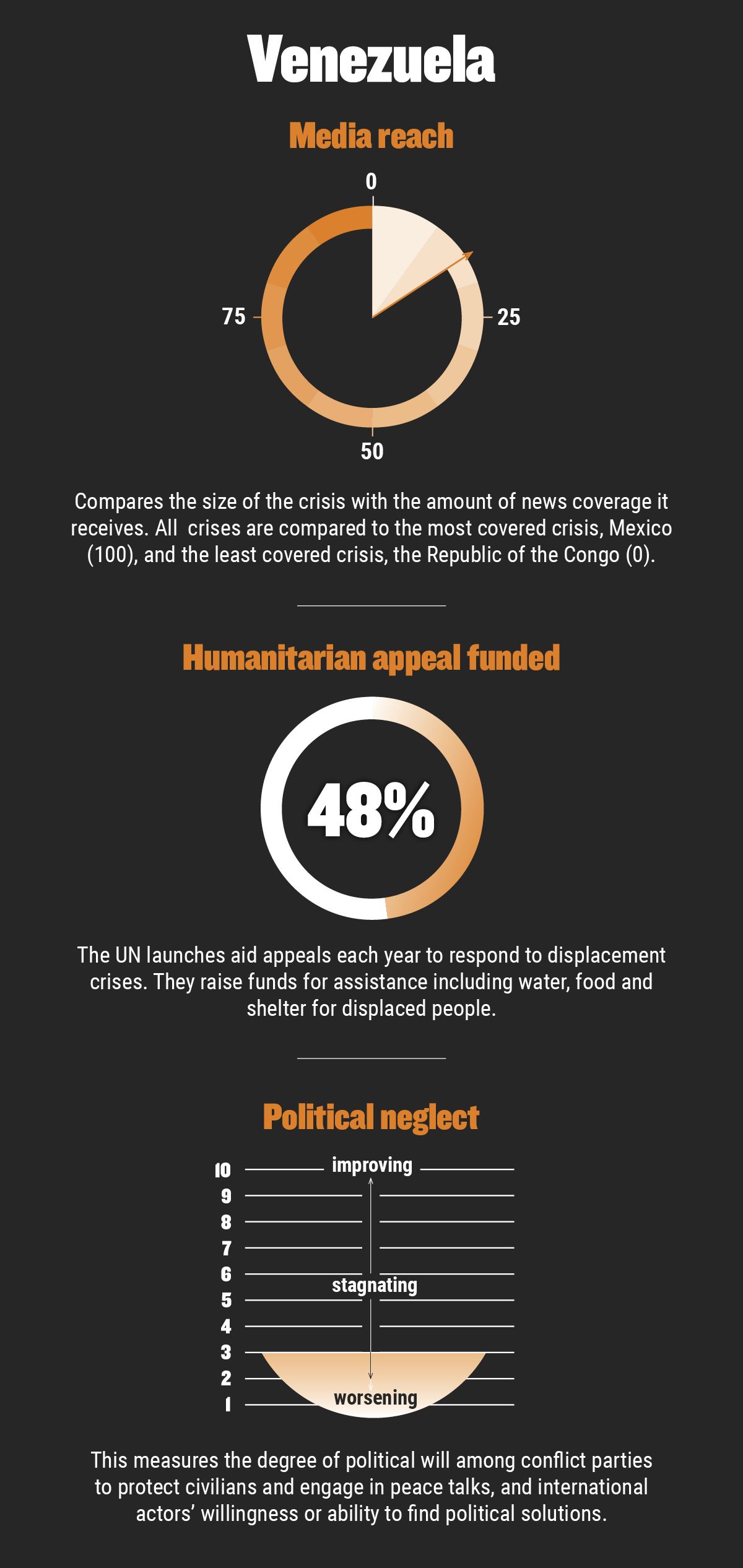

5. Venezuela

2018 ranking: 6th

Massive protests broke out in Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, at the start of 2019. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators took to the streets calling for political change. The subsequent political battle between the government and opposition led to an impasse that remained unresolved into 2020, with no successful national or international mediation efforts.

Seven years of economic freefall and a socio-political crisis prompted one of Latin America’s largest population movements of the century. An average of 5,000 people a day fled across the border in April 2019. By the end of the year, close to five million Venezuelans had fled since the start of the crisis in search of a better and more secure life, burdening an already struggling region.

Inside Venezuela, the economic and political instability led to falling oil prices, the collapse of major exports, hyperinflation and economic sanctions. The economy contracted by more than 25 per cent over the course of the year. This had devastating humanitarian consequences for over seven million Venezuelans who struggled to access basic services.

Food prices skyrocketed while peoples’ purchasing power was drastically reduced. The minimum wage only covered 3.5 per cent of the basic food basket. Some 6.8 million people suffered from undernourishment, a fourfold increase in only five years. Many people did not have access to water, fuel or electricity.

Venezuela’s humanitarian appeal for internally displaced people came late, was small compared with needs and was one of the worst funded appeals in the world, with only 34 per cent of the required money donated. The aid appeal for Venezuelan refugees in the wider region also failed to attract donor support, and was just 52 per cent funded by the end of the year. The dire lack of resources and lack of political will are the principal reasons Venezuela was one of the most neglected crises in 2019.

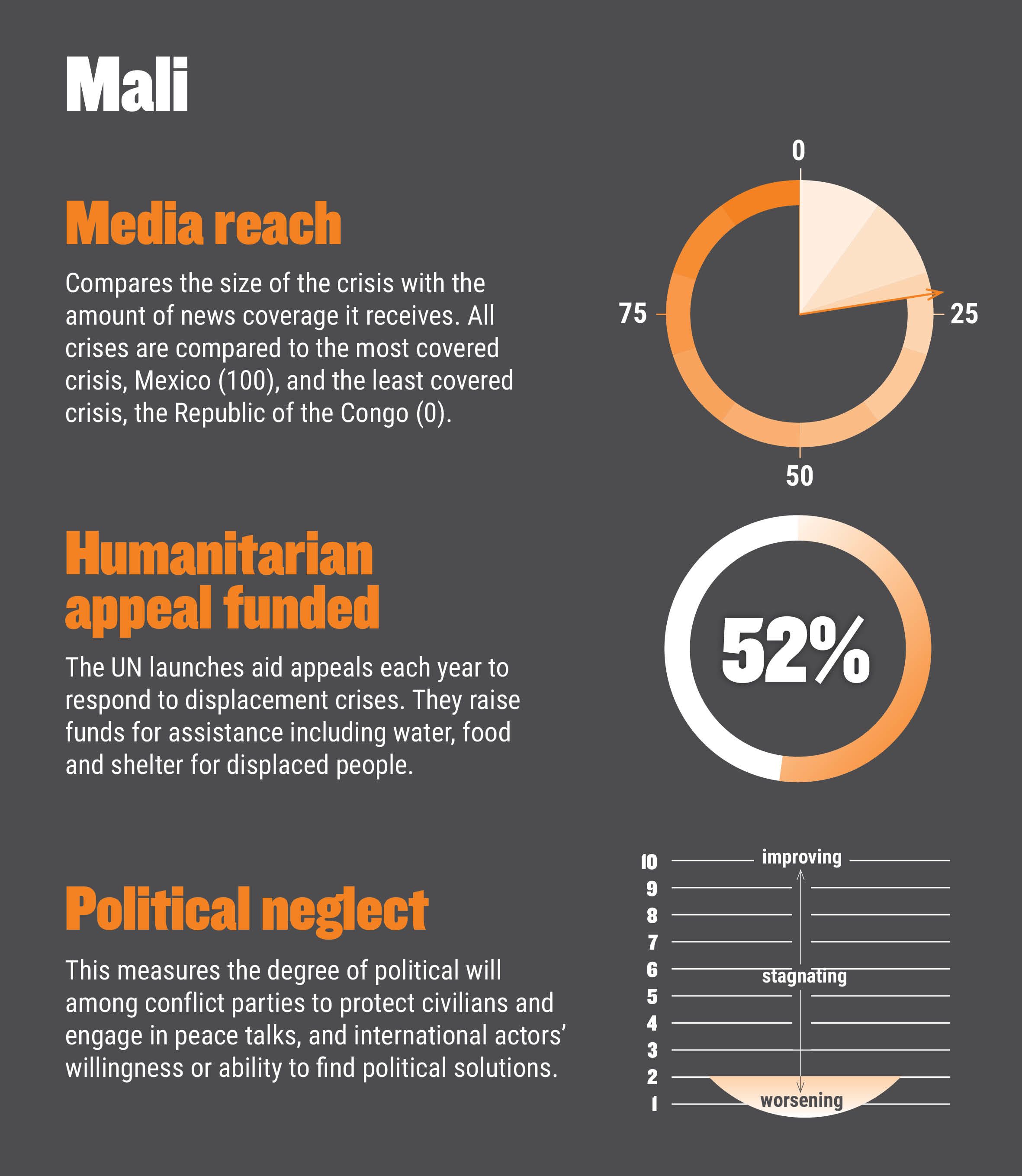

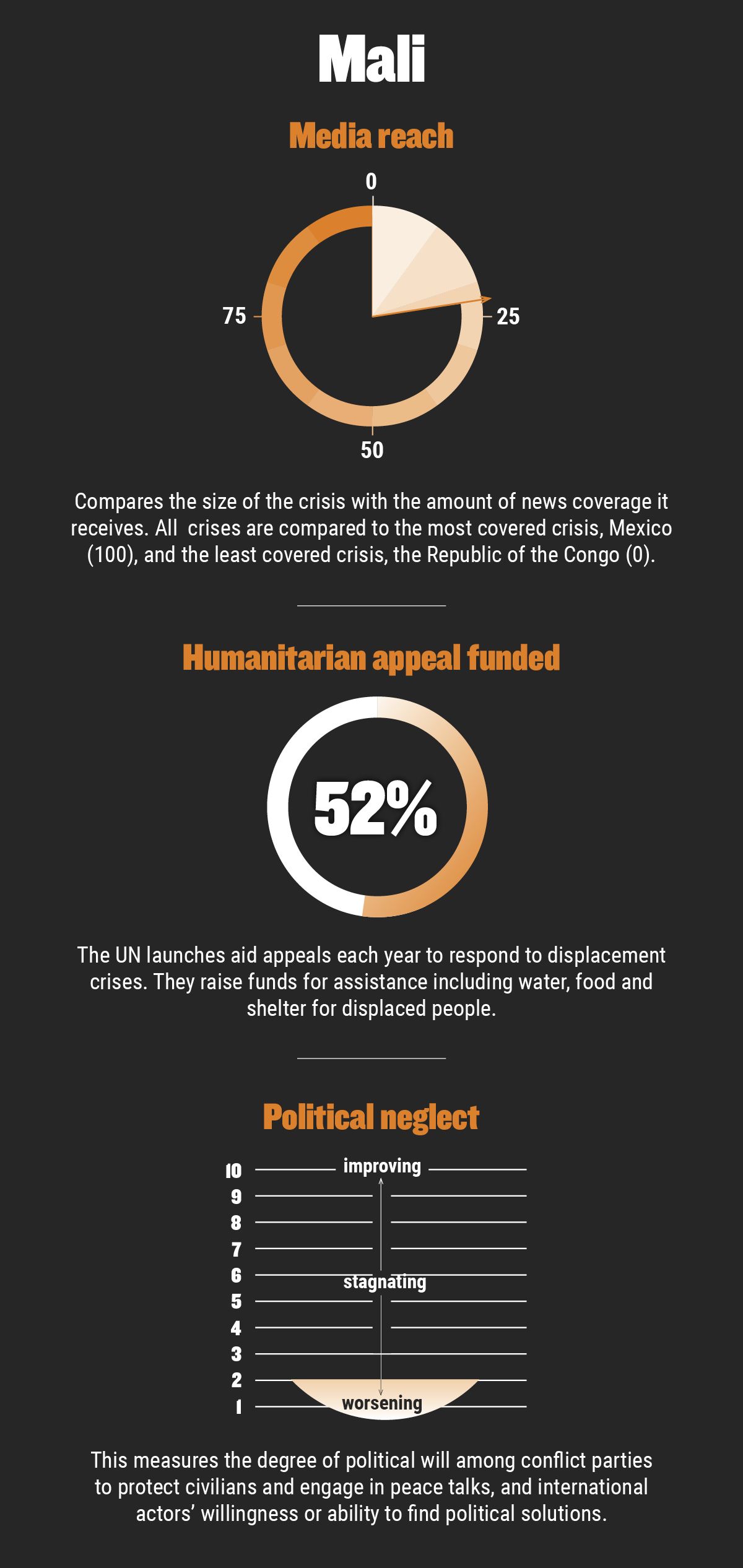

6. Mali

2018 ranking: 7th

Mali climbed up the Neglected Crises list in 2019, as conflict intensified and spread from the north of the country to central and western areas. Insecurity spilled over the border into neighbouring Burkina Faso and Niger, igniting a new regional crisis in the central Sahel.

Brutal violence battered communities. Some 208,000 people were internally displaced by the end the year, a sharp increase from 120,000 in 2018. Attacks against civilians were relentless, with 1,343 security incidents recorded throughout the year, the majority of them in the crisis epicentre of Mopti. An estimated 900 civilians were killed and 545 were injured.

The United Nations, France and G5 West African leaders continued to provide primarily a military response to stabilise the country, under the umbrella of counter- terrorism operations. But there was no significant positive impact of national and international military operations to protect civilians. At times, these operations incited revenge attacks and added to the violence, with significant humanitarian consequences.

Despite the intense international military attention, humanitarian funding for the millions suffering and investments in good governance were sorely inadequate. The 2019 aid appeal was just 52 per cent funded.

Media attention was also lacking, with most atrocities taking place away from the international spotlight. One violent attack that received coverage was a massacre in March in the Mopti region, where over 150 people were killed. The prime minister resigned after the massacre. However, the 2015 peace accord made little progress throughout the year towards ending the bloodshed.

Violence continued unabated in the first half of 2020. Some 73,000 people had fled their homes by May, many for the second or third time.

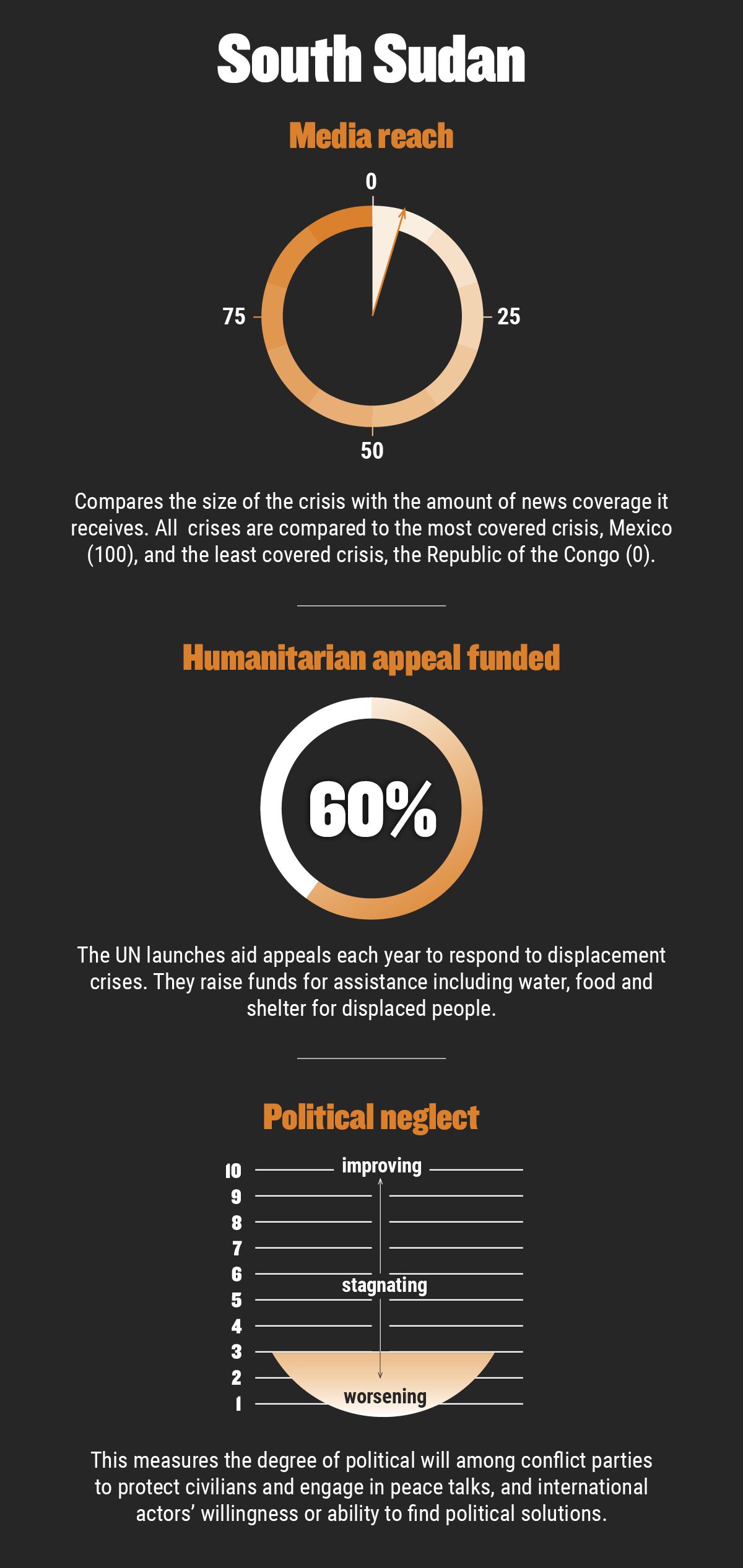

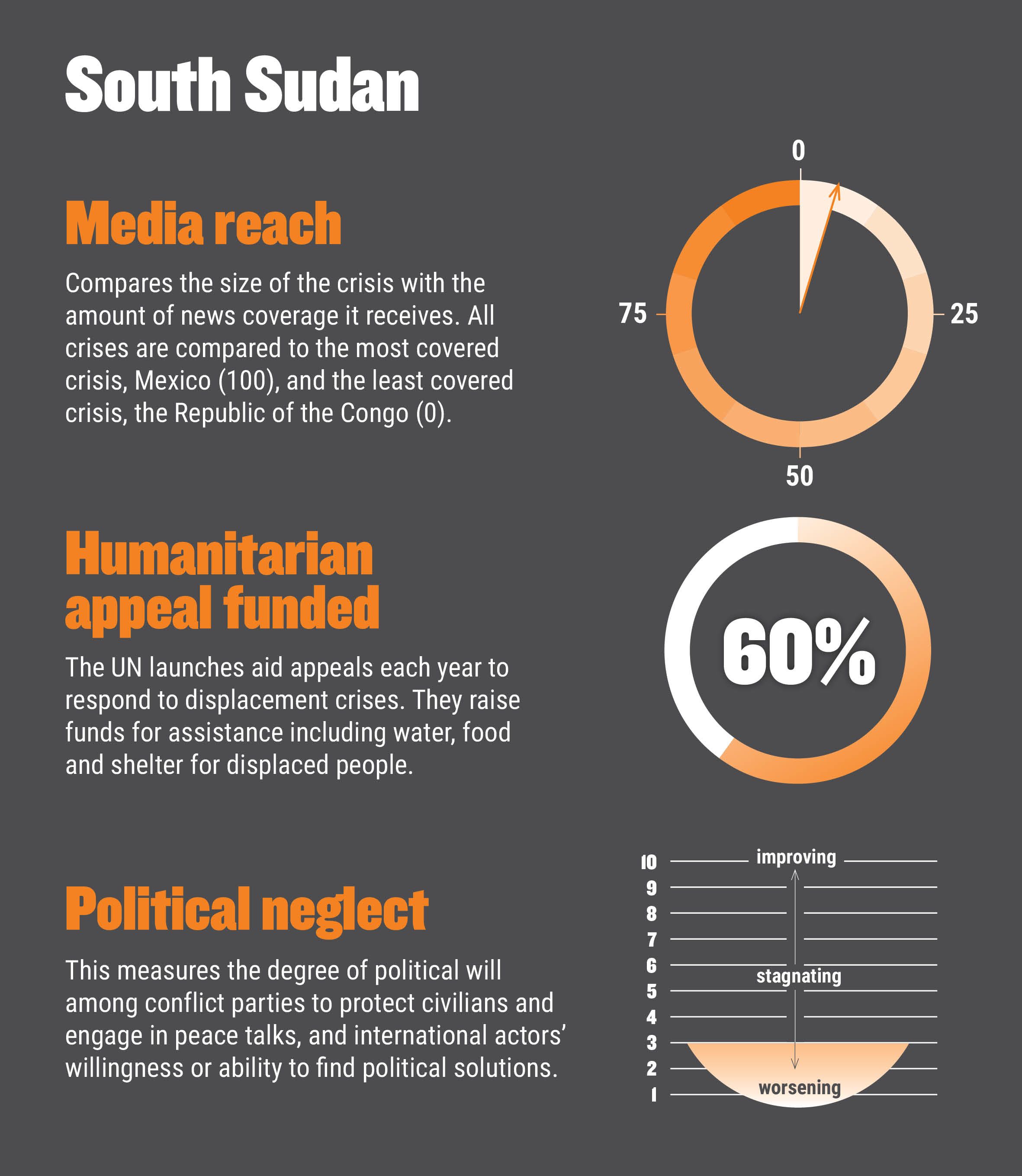

7. South Sudan

2018 ranking: New

South Sudan took tentative steps towards stability in 2019. While the 2018 peace agreement held firm in most parts of the country, pockets saw spikes in armed violence, intercommunal fighting and cattle raiding. Tens of thousands of people were newly displaced by fighting between armed groups, particularly in the states of Central Equatoria, Jonglei, Lakes, Upper Nile and Warrap.

Over 900,000 people were affected by widespread flooding which devastated agricultural activities and livelihoods, exacerbating already high levels of hunger. Vulnerable communities were pushed into even deeper levels of need.

2019 saw record hunger levels in South Sudan, with some seven million people unable to feed themselves and malnutrition rates at 16 per cent, surpassing the global emergency threshold. While the seriousness of food insecurity was linked to the flooding, food security indicators had not improved since the peace deal was signed the year before.

Protection concerns remained significant throughout the year, with communities expressing fear over persistent insecurity, human rights violations and gender-based violence. More than two thirds of the population relied on humanitarian assistance.

Progress on implementing the peace agreement was slow, and several extensions were granted to the deadline for forming a unity government. The situation appeared largely unchanged by the end of 2019. The political drama between the president and his former deputy attracted some media attention, but largely failed to address the deep humanitarian crisis facing the nation.

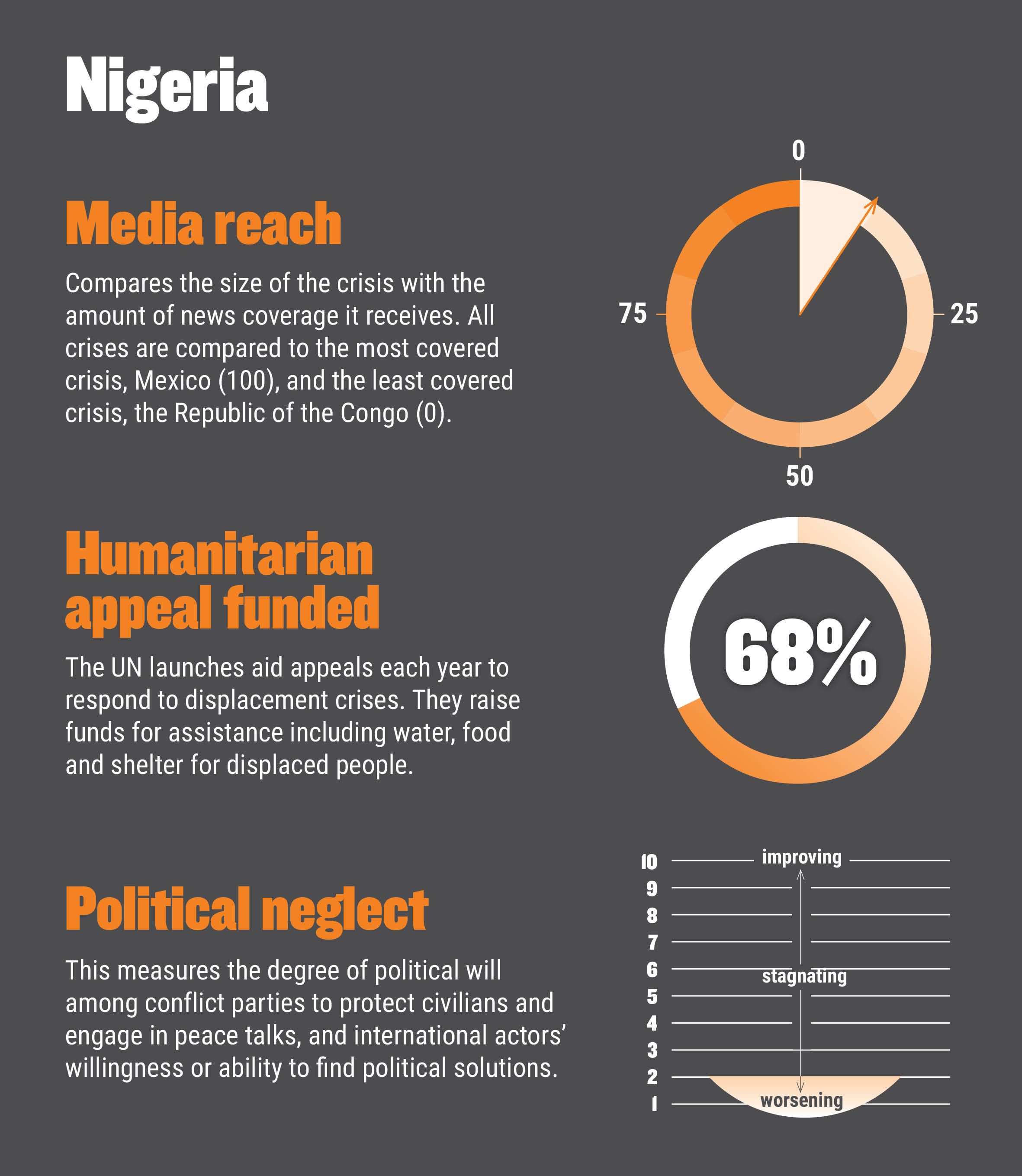

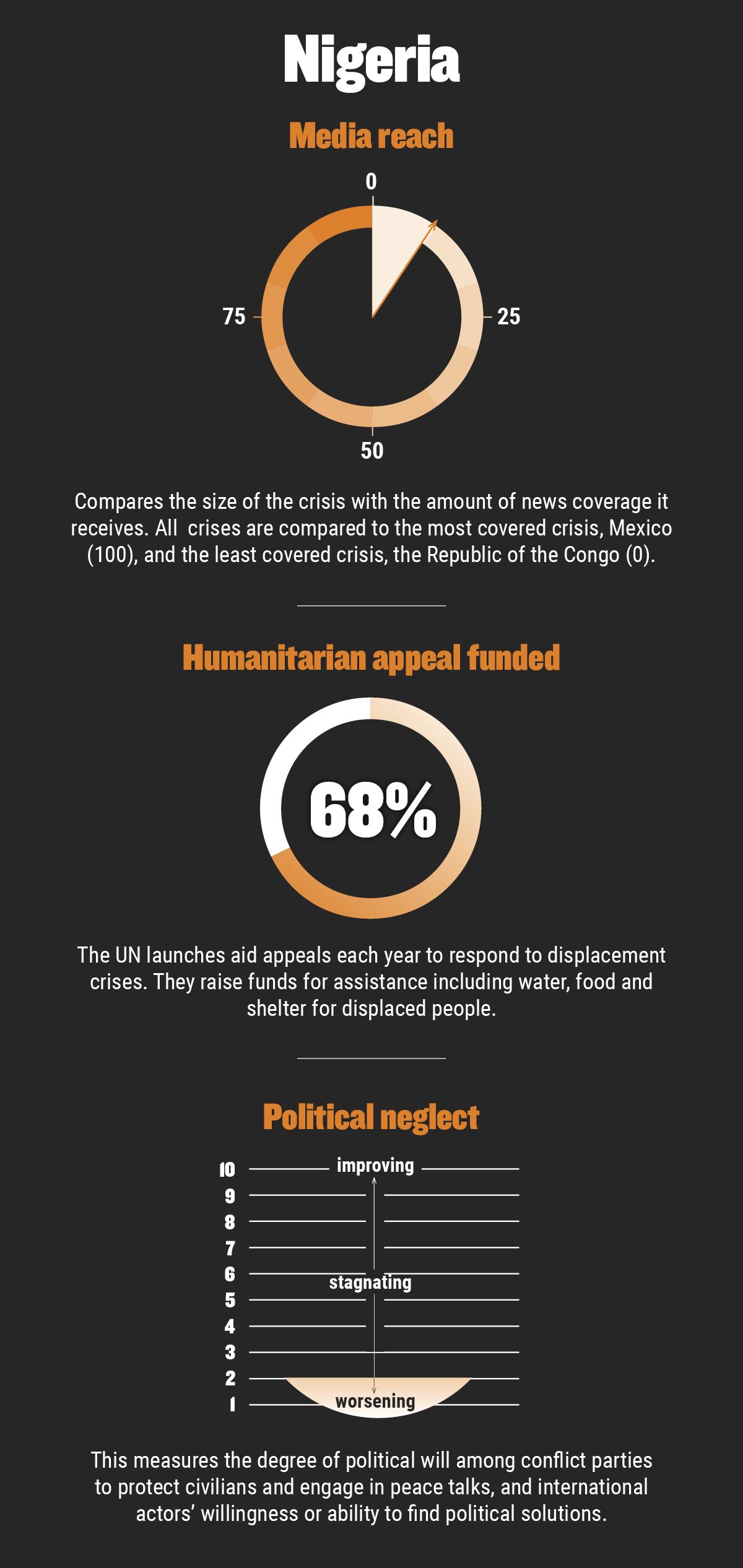

8. Nigeria

2018 ranking: New

Over a decade on, the conflict in north-east Nigeria between government forces and armed groups, including Boko Haram, was far from over. Civilians continued to be caught up in the violence throughout 2019. Climate change also caused people to flee their homes. Extreme dry conditions ignited fires in displacement sites, and large-scale flooding impacted communities during the rainy season.

An increase in insecurity in 2019 saw military operations and attacks on villages force 105,000 people to flee across the north-east. Over seven million people relied on humanitarian assistance to survive in the worst-affected states of Adamawa, Borno and Yobe.

The overwhelming majority of the north-east remained inaccessible to aid agencies due to active hostilities, threats of attack, and military restrictions that limited aid delivery to government-held “garrison towns”. These towns had little infrastructure, so many displaced families were crammed into tiny patches of land and received hardly any humanitarian support to meet their basic needs.

With minimal access to the worst-affected communities, the overall humanitarian crisis remained largely untold. International media and political attention largely focused on the security side of Nigeria’s conflict, overlooking its toll on civilians.

The humanitarian crisis is expected to deteriorate further throughout 2020, and close to four million people are forecast to be food insecure in the north-east.

9. Central African Republic

2018 ranking: 3rd

The conflict in the Central African Republic remained one of the worst in the world in 2019, in terms of the proportion of the population affected. Insecurity engulfed most of the country, with over half of all civilians relying on humanitarian aid to survive as a result.

Since the renewed outbreak of violence began in 2013, hundreds of thousands of people continued to be uprooted from their homes. A quarter of the population have been forced to flee – half of these have crossed into neighbouring Cameroon, DR Congo or Chad for safety.

The signing of a landmark peace agreement in February 2019 saw the formation of a new government. Despite this, armed groups continued to commit serious human rights abuses against civilians during the year. Over 70 per cent of the country was beyond the control of the new government ten months later.

The UN recorded an increase in extreme violence against civilians. Violations of international law continued unabated, and civilians and humanitarians were unable to move freely to access or provide aid. Attacks on aid workers continued in 2019, with five humanitarians killed and 42 injured in the line of duty.

The peace deal garnered a moment of media attention for the Central African Republic, but the humanitarian crisis remained largely absent from the global news headlines over the year.

The country entered 2020 faced with new waves of violence in the north-east and south-east, indicating the new year would offer little respite to weary civilians.

10. Niger

2018 ranking: New

Another newcomer to the Neglected Crises list, Niger was struck by a triad of conflict, climate change and chronic hunger in 2019.

In the shadows of its neighbours, the country carried some of the burden of several conflicts in the Sahel region. In the south, refugees crossed the border from Nigeria fleeing from armed groups and insecurity. In the west, refugees sought protection from violence in Burkina Faso and Mali.

Inside Niger, attacks by armed groups, banditry, intercommunal clashes and state military operations forced 440,000 people from their homes. Food insecurity threatened the lives of over 1.6 million people. Niger was also highly vulnerable to disasters, with some 227,000 people impacted by flooding over the year.

The political situation in Niger was more stable than in neighbouring Burkina Faso and Mali. However, the imprisonment of the opposition leader and presidential candidate in November ignited allegations of an increasingly authoritarian rule.

The central Sahel crisis continued in Niger into 2020, with the western Tilaberi region seeing attacks by armed groups and large military operations, and insecurity in Nigeria bringing 23,000 refugees across the border by May.

We recognise that the same formula will not work to raise the profile of every neglected crisis, but the recommendations below provide some practical steps that particular groups can take to improve the attention neglected crises receive.

To politicians/UN Security Council:

- Increase diplomatic efforts to find political solutions to neglected conflicts. Focus on helping solve emergencies according to their severity, rather than the amount of media attention they receive, the geopolitical importance of the region, or the partisan interests of the great powers.

- Ensure that counter-terrorism policies do not have a negative impact on humanitarians’ ability to reach communities in need.

To donors:

- Provide humanitarian assistance according to the needs of people affected by crises, and not according to geopolitical interests or the amount of media attention.

- Increase flexible and predictable funding in line with the commitments of the Grand Bargain, to improve the supply of funding to those who need it, when they need it.

- Build on existing best practices to ensure funding is flexible and predictable.

- Increase the appetite for risk to allow work in hard-to-reach areas and improve risk sharing among different actors. Humanitarians are needed most in places where armed groups operate and where governance is weak. But in the hardest-to-reach areas, too few NGOs are present, and donors must be willing to provide sufficient funding to manage the risk.

- Encourage increased engagement with development organisations in fragile crisis settings. This includes enabling funding to be moved quickly to meet immediate humanitarian needs if a situation deteriorates.

- Ensure the response to the Covid-19 pandemic does not divert funding from existing neglected crises.

To journalists and editors:

- Prioritise crises according to humanitarian needs or objective levels of severity.

- Do not give up. Continue to look for new angles and stories that have gone untold from protracted crises, and report in a way that focuses on solutions and does not contribute to exacerbating conflicts.

- If red tape such as lack of media permissions or visas hinders reporting from a crisis, use media platforms to advocate for the necessary change.

- Engage in the protection of press freedom to ensure domestic reporters working in crisis-affected countries can continue to report on the humanitarian consequences.

- Send staff to security training and provide them with security and protection when they are in conflict areas, so that they can report more safely.

To humanitarian organisations:

- Use flexible funding to support neglected crises.

- Avoid crying wolf. Do not push for increased funding for already well-funded crises, as this can have an impact on the donors’ ability to make money available when and where it is really needed.

- Get humanitarian needs overviews and response plans in place in a timely manner, and ensure aid appeals reflect the real needs. Do not adjust appeals downwards for crises where the available funding is expected to be limited.

- Improve collaboration and coordination between organisations on the ground. Optimise the use of resources and avoid unnecessary competition for the limited resources available.

- Invest in advocacy. Often countries that receive the least funding cannot afford advocacy and media resources, creating a vicious circle and making it difficult to lift these crises out of neglect.

To the public:

- Read up about neglected crises and support quality journalism that covers forgotten conflicts.

- Use your voice and speak up about these crises.

- Check the humanitarian policies of political candidates and parties before voting. Ask your politicians about these crises and push for them to take political initiatives.