“We don’t bungee in from helicopters”

How we really reach displaced people in the world’s most dangerous places

Accessing people in need is becoming more difficult and unsafe. Still, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) helps people in some of the most dangerous areas of the world. “It isn’t because we swoop in like cowboys; it’s by way of strong principles,” says Suze van Meegen, our adviser in Yemen.

68.5 million people are displaced and 133.8 million people need humanitarian assistance. Humanitarian organisations face enormous challenges in their quest to deliver aid to the people who need it the most.

Helping people in conflict zones and highly insecure areas is not an easy task, but if we fail, people in need of aid will face greater suffering.

In 2017, 36.4 million people in need did not receive the vital aid they needed. The more difficult it is to reach an area, the less likely people who live there are to receive help from humanitarian agencies. However, it is often in the areas hardest to reach that people need aid the most.

Too many international humanitarian actors focus their operations in relatively safe areas, according to the report “Presence and proximity – to stay and deliver, five years on”. The imbalance is partly explained by the many challenges that humanitarian organisations face.

“There is no assistance, no food, no health care.”

Nyiragine, living in Mungote displacement camp in DRC.

Nyiragine, an eighty-five-year-old woman lives in Mungote displacement camp in the North Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). She has to beg, to get something to eat. “We are suffering extremely,” she says.

Despite huge needs, when NRC got to Mungote displacement camp early 2018, there were no humanitarian agencies working to help people in the camp.

In DRC, violence and clashes between armed groups threatens our ability to reach people in need.

What makes an area hard to reach?

Armed conflict

We often work in areas with armed conflict, making some areas even harder to reach. Humanitarian organisations need access to conflict areas, without jeopardising the security of our employees. Fighting between armed groups, land mines, and violence against humanitarian workers contribute to increased insecurity.

Humanitarian workers are no longer only randomly affected by violence, but have become targets for violence. In 2017, there were 158 major incidents of violence against humanitarian operations and 139 aid workers were killed, according to the Aid Worker Security Report.

Natural disasters and a lack of infrastructure

Natural disasters and poor infrastructure, such as bad roads or poor means for communication, makes it difficult to operate in the locations where people need help. Sometimes humanitarian aid organisations struggle to enter an area due to damaged roads. In other cases, aid planes drop food on the ground because there is no road to access the area. Airdrops are very expensive, ineffective and often our last resort. The ideal solution is to be present on the ground.

Bureaucratic challenges

Whether it is dropping aid with a plane or arriving to an area with a convoy on the ground, humanitarians are guests in a country. We need to get permission to work and ask for admission to enter certain areas.

Authorities might frequently deny access to humanitarian agencies or interfere with their activities in the country. Sometimes authorities do not recognise the severity of the humanitarian needs.

As a consequence, humanitarian organisations spend a lot of time doing paperwork to get the right permissions.

Eritrea, Syria, Venezuela and Yemen are the countries most difficult to reach, according to ACAPS’ Humanitarian access overview. A few humanitarian organisations are able to operate there, but the countries are close to inaccessible for most non-governmental organisations.

Active hostilities, violence against humanitarian personnel, denial of needs and restriction of movements make it extremely difficult to help people in some areas of these countries.

In the face of these challenges, humanitarian agencies, like NRC, work hard to get in.

Inaccessible Yemen

Over 22 million people need humanitarian assistance in Yemen, a war-ridden country where people in need live in some of the hardest to reach areas in the world.

“We never expected something like this to happen so close to our home.”

Abdulrahman Mohammed Jahia in Yemen.

His neighbour’s house was bombed.

Armed conflict and damaged infrastructure are huge impediments to accessing humanitarian aid for people in Yemen. Van Meegen, our protection and advocacy adviser in Yemen, talks about a war that stretches across most of the country, though some areas are worse affected than others.

“Across many of the highly populated areas, neighbourhoods are being hit with airstrikes, thousands of them since the war started in 2015. In other parts, clashes are happening on the ground, with gunfire, missiles and an increasing number of landmines.”

“We engage with both parties to the conflict to help secure safe passage for our staff.”

Suze van Meegen, Protection and advocacy adviser in Yemen.

The result of engagement with both parties could be getting an agreement that no bombing take place on the routes where aid will be transported and distributed for a given period.

“Sometimes access can be arranged more simply but often, where fighting is most intense, it can take weeks or months to gain access and reach a community.”

Some areas in Yemen, where large numbers of people are in urgent need of aid, are currently inaccessible due to the conflict. “But we continue to exhaust every means by which to get aid to people who need it,” says van Meegen.

Constant bureaucratic constraints are another challenge that humanitarian organisations face in Yemen. Negotiations and paperwork to get permits are part of everyday activities to get access.

Despite the immense challenges, NRC expects to reach close to a million people in Yemen by the end of 2018 - “This isn’t because we swoop in like cowboys; it is by application of strong principles and a series of carefully calculated steps,” says van Meegen.

Nearly inaccessible CAR

Nearly 70 percent of the Central African Republic’s (CAR) territory is controlled by armed groups. 63 per cent of the country’s population, 2.9 million people, are in need of humanitarian assistance. 100 percent of basic social services are provided by humanitarian actors.

“Our goal is to be where people have needs.”

Eric Batonon, Country Director in CAR

Some areas are more difficult to reach than others. With many armed groups operating in the country, CAR is one of the most dangerous places to deliver aid.

Families who are forced to flee find themselves lacking everything they need to survive, such as shelter and clean water.

“We don’t have access to anything.”

Angèle, mother of six and displaced.

“We don’t have a house, my children are exposed to the elements and we’re all sharing one water source, which isn’t enough to fill the needs of everyone living in this area,” deplores Angèle.

Targeting humanitarians in CAR

Humanitarians are often targeted, risking robberies, kidnapping or worse, being killed. “We have to be careful and protect our colleagues,” says Batonon, explaining how humanitarian agencies sometimes have to withdraw from insecure areas completely. “This has disastrous consequences on populations in need.”

We continue our work, despite this challenging situation.

“We cannot give up.”

How do we work around the challenges?

The majority of conflicts in the world today occur within a country, often with several non-state armed groups involved. This results in more complex and unpredictable crises, making it even more difficult to get access to civilians in need. Additionally, conflicting parties increasingly disregard international law stating that humanitarian agencies should have access to civilians in need. Humanitarian organisations approach this challenge by negotiating access and getting acceptance.

Negotiation and acceptance

To get safe access on the ground, we need approval by all parties to the conflict and the communities in need. This can be a timely and tricky task.

The perception of humanitarian aid work can differ quite significantly from the reality, explains van Meegen.

“We don’t bungee in from helicopters or make a mad dash through gunfire. We work hard to build trust among parties to a conflict.”

Trust and acceptance can be built through careful negotiations, in addition to delivering timely and quality aid.

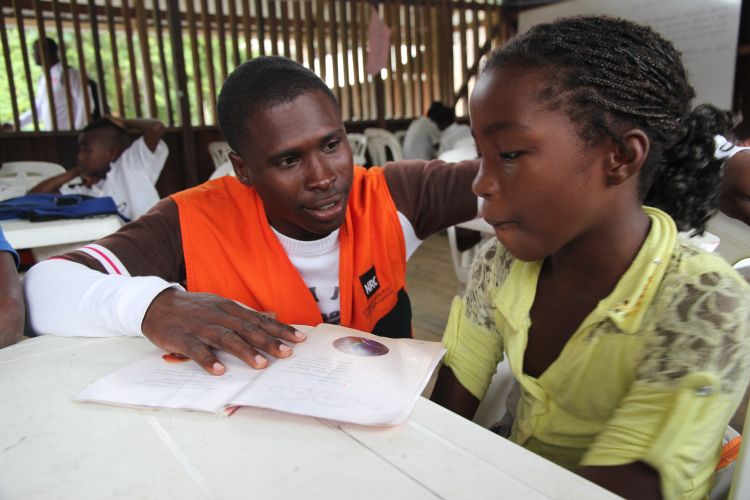

The modern superhero

Philippe Douryang, emergency team leader for NRC, has dedicated his life to reach people in need. With over 17 years of experience in emergency settings, Douryang has worked in crises like Darfur, the Central African Republic and Nigeria. His job is to negotiate us access to hard-to-reach areas. In some areas, we has been the first humanitarian agency to enter and assist displaced people in a conflict zone, thanks to him.

He explains how he works to get access to areas that are hard to reach:

“First, you have to get more information about the geopolitical situation.”

Philippe Douryang, emergency team leader for NRC

“Who are the key people involved in the conflict, what are their aims and the links between each other. Because the context varies even within a country, you have to really understand it before you can do anything else,” he explains.

To do no harm, NRC always makes sure that our work and interventions do not add tensions or escalate conflict. We begin our work to get access with an initial analysis of the context. We consider conflict sensitivity and whether our intervention might increase harm.

“After that, you have to know how to approach the key actors,” he says. Douryang has met with government representatives, civilians and armed groups to negotiate access. “I approach them directly, and because of my previous research, they often already know who I am and why I’m coming,” he explains. “I introduce myself and we sit down and discuss.”

While negotiating, Douryang constantly has to measure the risk level and how to minimise it. “It is important to build trust, you have to put all info on the ground: why you are there and what you want to do.”

When negotiating, the humanitarian principles become highly important.

The humanitarian principles are extremely important to our work – it is what keeps humanitarian workers safe and enables us to respond effectively.

Acceptance is key to gain access to people in need. When negotiating with all parties to a conflict, not taking sides and impartiality is essential to gain that acceptance.

Adhering to the humanitarian principles distinguishes humanitarian organisations from political or military actors. A confusion, or if the organisation is seen as partial or not neutral, could jeopardise the safety of our workers and the people we help.

How humanitarian principles are followed affects humanitarian organisations’ credibility and reputation, and can affect future possibilities to negotiate access.

Humanitarian workers face many dilemmas when negotiating access and upholding humanitarian principles.

Let's have a look at this example: You want to deliver aid to civilians in an area where armed groups are in charge. The government in the country might not allow you to enter that area without an armed escort. If you choose to enter with the escort, you might no longer be perceived as neutral and independent, thus violating the trust of other armed groups. If you refuse, people will suffer and you can undermine the principle of humanity.

What would you do?

You can learn more in our online introductory course on humanitarian access.

Read more: how we deliver aid in Syria

Helping in hard times

Aiming to be a leading displacement organisation in hard-to-reach areas, we reach people in need in countries such as Syria, Yemen and Eritrea. In addition to negotiating access, we train our staff and find creative ways to reach people, like working through local partners and using electronic cash transfers. Using electronic cash transfers minimizes security risks. People forced to flee can register as recipients and continue to receive support after they have travelled back to the areas that we cannot reach.

Read more: Why not cash?

This is how we access people in the hardest to reach areas.

“We are literally saving lives here.”

Fadzai Manyere, Project officer and team leader in South Sudan