A few countries take responsibility for most of the world’s refugees

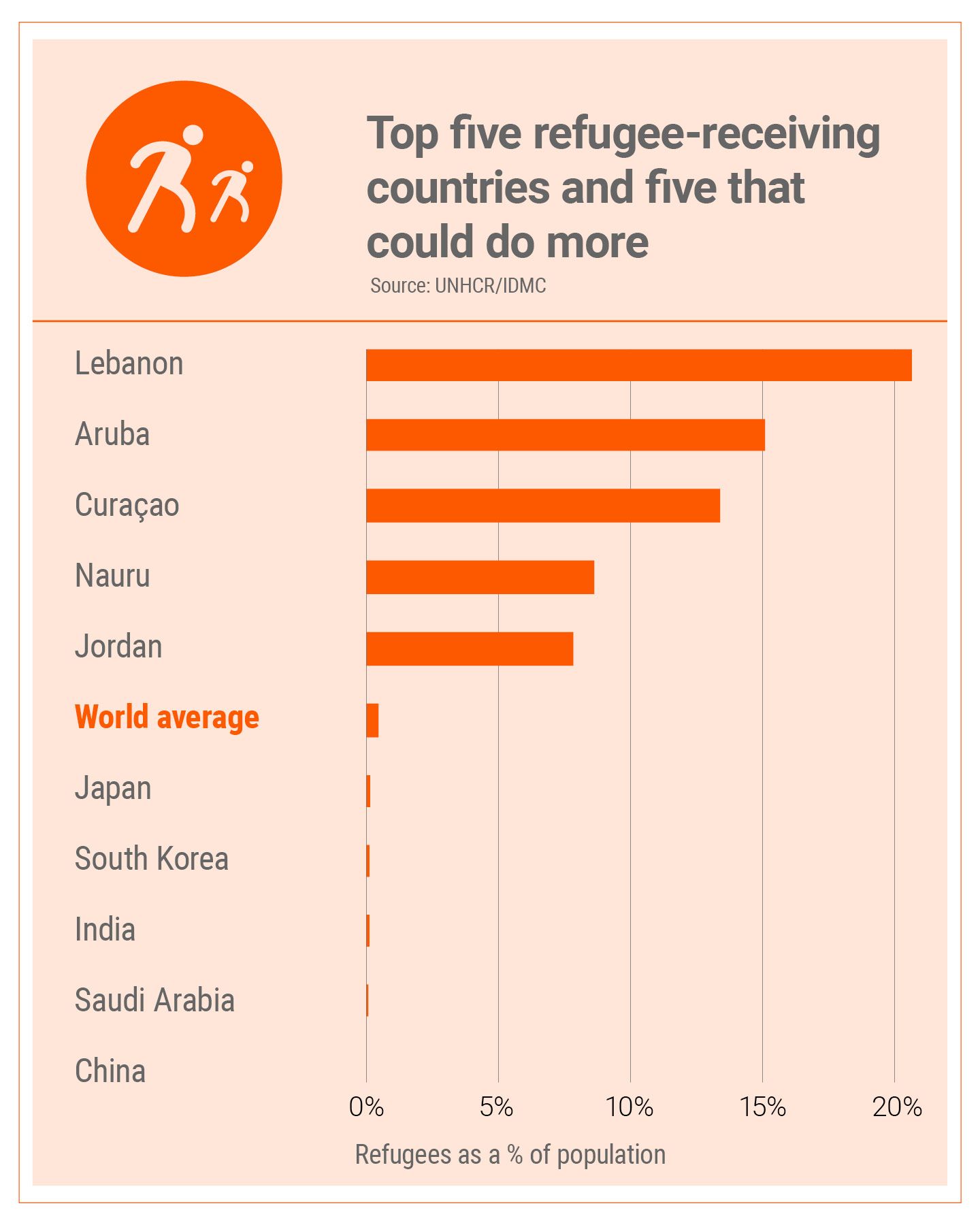

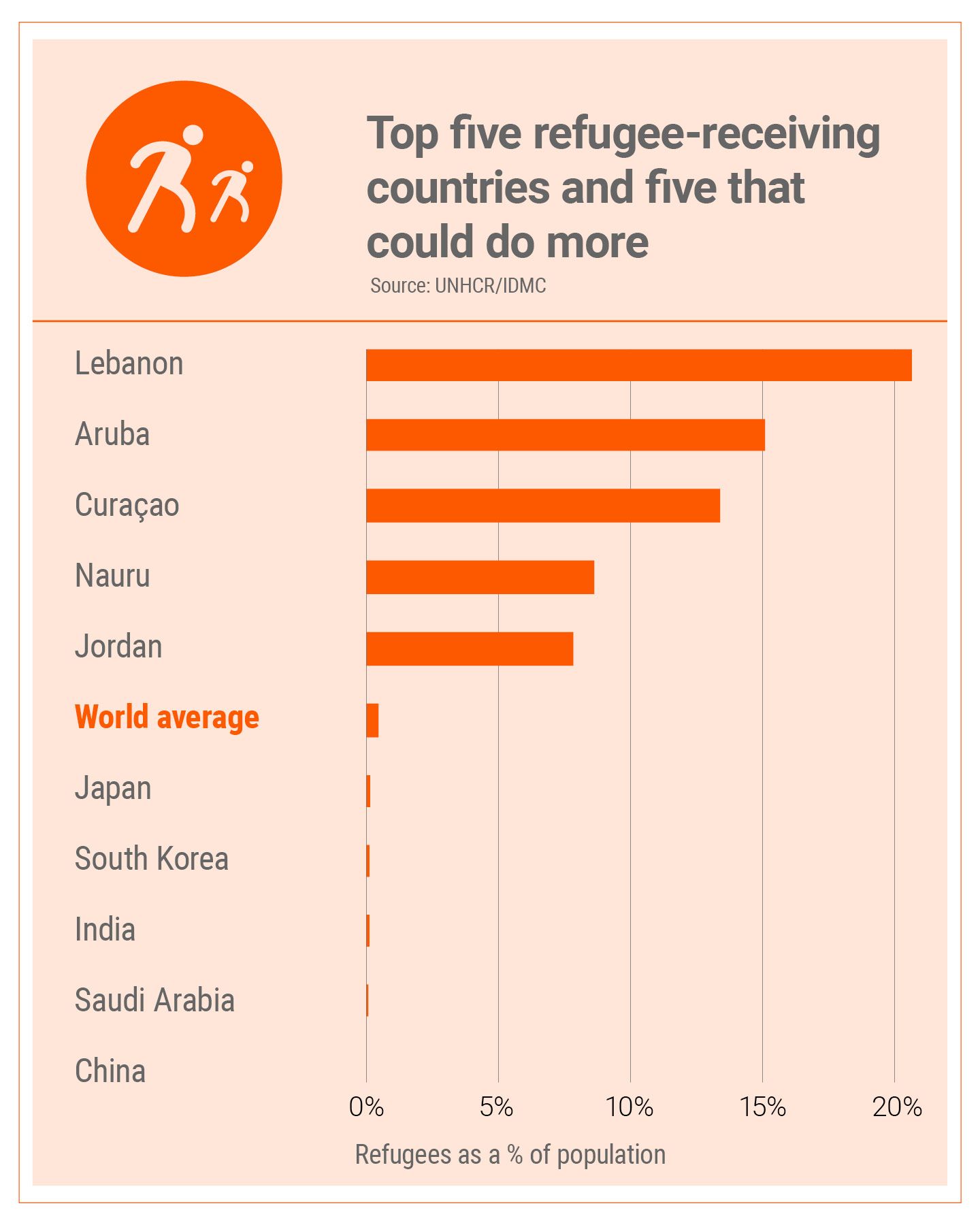

Over 33 million refugees have been granted protection in another country in the last ten years. A small number of countries are bearing almost all the responsibility, while most countries in the world have scarcely received any refugees at all.

The failing division of responsibilities means that some recipient countries, such as Lebanon, are suffering under a heavy burden. But most of all, it affects the refugees themselves.

In total, there are more than 108 million displaced people in the world today. Of these, 45.9 million are refugees who have fled to another country. This is a historically high figure, and a staggeringly high number of people in need of protection. However, it is entirely possible to offer all displaced people a dignified life, if we only have the will to do so.

This article was first published in November 2020 and updated on 30 June 2023.

In Lebanon, one in four people is a refugee

Lebanon, with a population of 6.8 million, is currently hosting an estimated 1.5 million refugees from Syria. The exact number is uncertain because the national authorities demanded that the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) stop the registration of new refugees in 2015. In addition, hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees live in the country.

Lebanon itself has been ravaged by a civil war that lasted from 1975 until 1990. It is a densely populated country with a fragile political balance between different ethnic and religious groups.

Even before the large influx of refugees from Syria, the country was in a precarious economic situation. Lebanon is dependent on importing most of what it needs and has long kept its economy going through foreign loans and financial transfers from Lebanese nationals abroad.

Since 2019, the situation has gone from bad to worse, with large-scale popular protests eventually leading to the Prime Minister’s resignation. Then, in 2020, Beirut was shaken by a huge explosion, which killed more than 200 people, injured more than 6,000 and left over 300,000 homeless.

Unemployment is sky-high. The country’s currency has collapsed, reaching a historic low in May 2022, meaning much of the population is no longer able to afford the necessities of survival. On top of all this came the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by a rapid rise in food and energy prices as a result of the war in Ukraine.

More than 50 per cent of the population live below the poverty line. For Syrian refugees, the figure is even higher, with 83 per cent living in extreme poverty.

Perhaps never before has a country that receives refugees had a greater need for the rest of the world to step up and help.

Here, you can see which countries have received the most refugees in the last ten years.

These siblings fled from Syria several years ago. They now live in Beirut, Lebanon. Photo: Zaynab Mayladan/NRC

These siblings fled from Syria several years ago. They now live in Beirut, Lebanon. Photo: Zaynab Mayladan/NRC

The explosion in Beirut on 4 August 2020 caused extensive damage to Lebanon’s capital. Photo: Aly Mouslmani/NRC

The explosion in Beirut on 4 August 2020 caused extensive damage to Lebanon’s capital. Photo: Aly Mouslmani/NRC

More countries must take responsibility

While countries such as Lebanon, Uganda and Sweden have received large numbers of refugees year after year, many countries have received almost none and are doing everything they can to prevent refugees from coming to their country.

Several of these are rich and populous countries that are much more able to help than many of the countries taking the greatest responsibility today.

Some of the richest countries in the world do almost nothing. China, the world’s second largest economy, with a population of 1.4 billion, has accepted only 526 refugees in ten years – 0.00004 per cent of its population size. Japan has the world’s third largest economy and a population of 123 million. Nevertheless, it has received just 16,150 refugees in the last ten years – 0.0013 per cent of the country’s population. South Korea is at a similarly low level.

The oil-rich Gulf countries are another example. Saudi Arabia has received 0.0015 per cent of its population size, and the other Gulf countries are at a similar level. For most of the last decade there have been brutal civil wars in both Syria and Yemen, in which several of these countries have been directly and indirectly involved. It is therefore particularly inexcusable that they have not given proper protection to more of the victims of the war and relieved some of the neighbouring countries such as Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

The Gulf countries have admittedly received a large number of Syrians as labour immigrants, but these have not been granted refugee status.

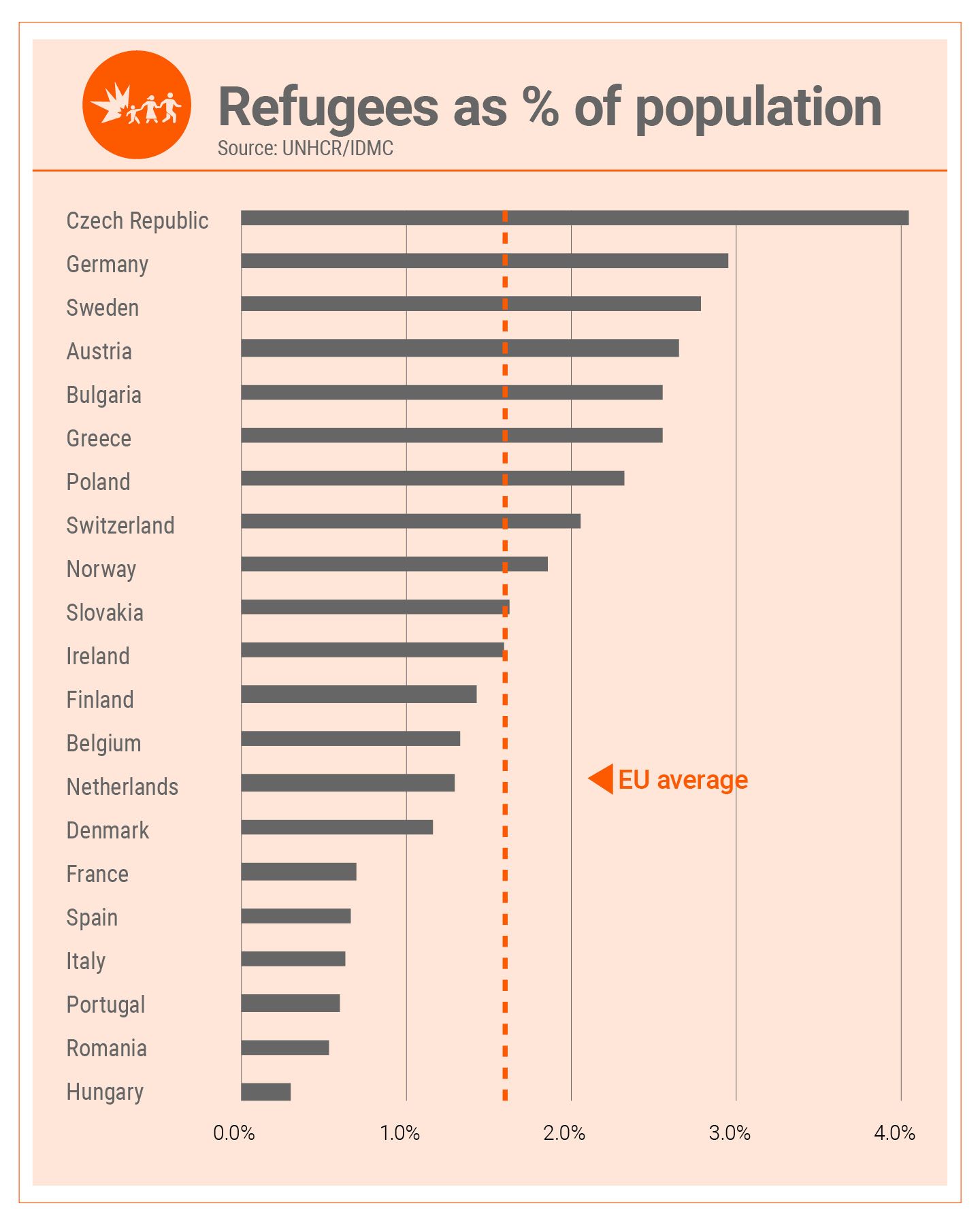

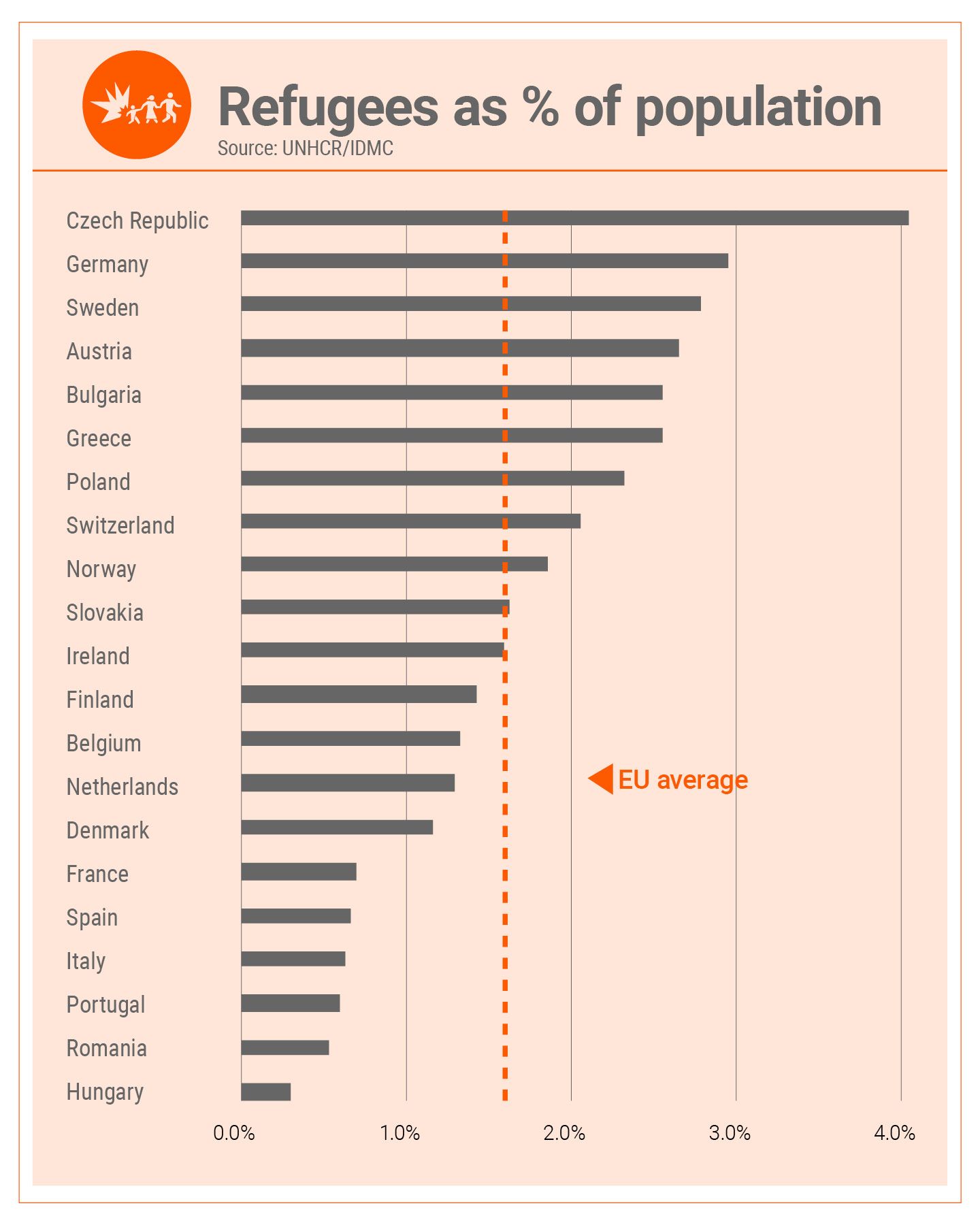

The EU is struggling to convince member countries to contribute

Many European countries have, historically, had little to be proud of. In total, EU countries have provided protection to 7.5 million refugees over the last ten years, which corresponds to 1.63 per cent of the population.

Although the EU as a whole has received a large number of refugees in the last ten years, this is because a few countries, such as Germany and Sweden, have taken responsibility.

Prior to 2022, Poland had only received the equivalent of 0.01 per cent of its population. With the exception of Bulgaria, all the other Eastern European EU countries had received less than 0.04 per cent. However, these countries received a large number of Ukrainian refugees in 2022.

In Western Europe, it is Portugal that has received the fewest refugees, at 0.61 per cent.

The Dublin Regulation has a major shortcoming

The Dublin Regulation is an agreement between European countries that determines who is responsible for processing asylum applications. In essence, it states that the first European country where refugees arrive must process their asylum applications and provide protection to those who are entitled to it.

For a long time, this was not complied with in practice, and most of those who arrived in Greece, Italy and Spain would travel on to countries further north in Europe to seek asylum. The refugees themselves often wanted to seek asylum further north, and the Mediterranean countries were happy to avoid the responsibility.

In recent years, this has changed. The large influx of refugees to Europe in 2015 led the EU to demand that the Dublin Regulation be practised consistently. This made it clear that the Dublin Regulation has a major shortcoming. It does not contain a distribution mechanism that obliges other EU countries to relieve those countries that take responsibility on behalf of the rest of the EU.

Graph showing the percentage of refugees received in each EU/EEA country between 2013 and 2022, excluding countries with a population under five million.

In 2015, the EU adopted a temporary relocation scheme that required other EU countries to receive asylum seekers from Italy and Greece for a period of two years. The decision was met with great opposition, especially in countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, which refused to accept the number imposed on them.

The strong opposition meant that there was no permanent arrangement for the division of responsibilities when the temporary agreement expired in 2017.

Graph showing the percentage of refugees received in each EU/EEA country between 2013 and 2022, excluding countries with a population under five million.

Graph showing the percentage of refugees received in each EU/EEA country between 2013 and 2022, excluding countries with a population under five million.

Disclaiming responsibility

In recent years, therefore, Italy and Greece have largely been left to themselves. They have received financial support from the EU to strengthen their asylum systems, but while some EU countries have voluntarily chosen to accept some refugees, most have refused to do so.

In Italy, this has led to the authorities increasingly refusing to allow boats with asylum seekers to dock in their ports. In 2016, 181,000 refugees and migrants came to Italy by sea, but that number dropped to 11,000 in 2019. However, after the country changed government, the numbers started to rise again, and in 2022 there was a sharp increase to 105,000.

In Greece, the 2016 agreement between the EU and Turkey led to a sharp drop in arrival figures. Turkey began to prevent boats from leaving shore, and those who managed to enter Greece risked being sent back to Turkey. But as the agreement made it difficult for Greece to return asylum seekers, arrival numbers started to rise again. In 2019, 60,000 asylum seekers came to Greece by sea and another 15,000 came across the border between Greece and Turkey.

From 2020, the numbers fell dramatically, to the lowest level in almost ten years, partly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021, just under 4,000 people arrived by sea, while 5,000 came across the land border. In 2022, the number rose again, with 13,000 people arriving by sea and 6,000 by land.

Amnesty International has documented that the Greek authorities are increasingly chasing asylum seekers back to the borders in so-called “pushbacks”, which helps to explain the sharp decline. In addition, Covid-19 restrictions have made it more difficult to cross national borders.

Greece’s capacity to process the large number of asylum applications has been inadequate, which has led to longer processing times. A large number of asylum seekers have been denied permission to leave the Greek islands where they have been living in overcrowded camps under appalling humanitarian conditions.

The poor reception conditions and difficulties with onwards travel have led to many people attempting to travel directly by sea to Italy instead. This had disastrous consequences in June 2023 when as many as 500 people were feared dead after a tragic shipwreck.

Islands in the Mediterranean have been overwhelmed by those who have crossed the sea, desperately seeking refuge. Image captured in 2015. Photo: NORCAP

Islands in the Mediterranean have been overwhelmed by those who have crossed the sea, desperately seeking refuge. Image captured in 2015. Photo: NORCAP

Migrants stand at the closed border between Turkey and Greece on 1 March 2020. Photo: Ahmed Deeb/dpa/NTB Scanpix

Migrants stand at the closed border between Turkey and Greece on 1 March 2020. Photo: Ahmed Deeb/dpa/NTB Scanpix

The fire in the Moria camp highlighted the need for a new EU policy

Children walk over a bridge in Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesvos on 5 March 2020. Photo: Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Children walk over a bridge in Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesvos on 5 March 2020. Photo: Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Aerial shot of Moria camp captured in December 2018. Photo: Jørn Casper Øwre/NORCAP

Aerial shot of Moria camp captured in December 2018. Photo: Jørn Casper Øwre/NORCAP

The worst conditions were found in the Moria camp on Lesvos. The camp had a capacity of 3,000, but housed more than 18,000 refugees and migrants at times. When the camp burnt down in early September 2020, 12,000 people were living there.

The fire led the EU to speed up the launch of a proposal for a new agreement to replace the Dublin Regulation. Many hoped that this agreement would contain a binding division of responsibilities, but they were disappointed.

The agreement stipulates that individual countries can contribute in different ways. Countries that don’t want to receive asylum seekers can instead contribute financially by providing support to those that do and undertaking to return asylum seekers who have been rejected.

In addition to the Mediterranean crossing, a large proportion of asylum seekers to European countries come via other routes. Germany is still the largest recipient of asylum applications in Europe, even though it is not at the EU’s outer border.

The war in Ukraine turned everything upside down

Ukrainian refugees gather at Przemysl train station, south-east Poland. Photo: IRC

Ukrainian refugees gather at Przemysl train station, south-east Poland. Photo: IRC

In February 2022, Russia launched a military operation against Ukraine, and millions of Ukrainians were forced to flee both within the country and over the border to neighbouring countries.

An irony of fate led to those European countries that have been most negative about receiving refugees from outside Europe, such as Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, becoming the largest recipient countries for refugees from Ukraine. Many fled to Poland, which now houses almost 1 million refugees.

The Czech Republic has gone from barely accepting refugees to being one of the largest recipients in relation to its population in the last ten years. Montenegro is now the country in Europe that has received the most refugees per capita, and ranks sixth in the world. Moldova, one of Europe’s poorest countries, is also among the countries in Europe that have received most refugees in relation to their population, having taken in over 100,000 Ukrainian refugees.

Both in Ukraine’s neighbouring countries and in other European countries, Ukrainian refugees have generally been well received. Many people have pointed out the contrast with the way refugees from other parts of the world are met in Europe. Legally, though, Ukrainians are in a different situation, as they do not have to cross borders with other countries to get to EU countries.

Even if European countries had wanted to keep Ukrainians out, they would not have been able to do so without violating the most basic principles of the Refugee Convention and the European Convention on Human Rights. Even before the war began, Ukrainians with modern passports had the right to travel freely within the EU for three months. They were therefore not obliged to seek asylum in the first European country they came to, unlike most other refugees who travel to Europe.

The biggest difference, however, is that both European states and the majority of their populations have been actively welcoming refugees. This is perhaps largely due to a sense of closeness both culturally and geographically, and a feeling that the Ukrainians are fighting a battle for what are considered “European values”.

Nevertheless, it should not be ignored that the different treatment received by refugees from Ukraine compared to those from countries outside Europe is to some extent also rooted in xenophobia, and in particular opposition to Muslim immigration. This is particularly noticeable in countries such as Poland, where fences have been erected on the border with Belarus and asylum seekers from the Middle East and Africa are being pushed back, while refugees on the border with Ukraine are being welcomed with open arms.

In 2022, the Czech Republic introduced border controls to prevent Syrian refugees from entering from Slovakia. Together with Hungary and Poland, the Czech Republic has refused to participate in the EU’s scheme for the relocation of refugees from Greece and Italy. The European Commission is now threatening the three countries with punitive measures if they do not change their position.

Everyone should contribute according to their ability

As we have seen, poorer countries have often taken the greatest responsibility, while some rich countries have also made significant contributions. As a group, middle-income countries come out worst, even though countries such as Lebanon and Turkey are lifting the average sharply.

The most populous countries in the world, such as China, India, Indonesia and Brazil are in this group. If more of these countries contributed to a better division of responsibilities, it would make a big difference. Several have experienced strong economic growth in recent decades and can no longer claim that they can’t afford to help displaced people. A country that can afford to host the Summer Olympics can also afford to receive a few thousand refugees each year.

The United States previously received almost 100,000 resettlement refugees each year and was the largest recipient of resettlement refugees in the world. Under Donald Trump’s leadership, this number was greatly reduced, and in 2020, the United States received fewer than 10,000 resettlement refugees. President Biden announced in May 2021 that the United States would once again support refugees and take in up to 62,500 resettlement refugees each year. In 2022, the United States accepted 29,000 resettlement refugees

In addition, under Trump’s leadership, it became much harder for refugees to seek asylum on the United States border with Mexico and many were sent back to countries such as Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. After Joe Biden took over as president, some of the measures were reversed and asylum arrivals to the United States have risen sharply. However, the Biden administration is under pressure, not least from its own party, to ensure that asylum numbers are kept low, which makes it difficult to remove all restrictions.

Despite these measures, however, the United States has received more refugees relative to its population than many European countries, and is on a par with the United Kingdom.

100 Chinese Renminbi banknotes. Photo: Maksym Kapliuk/NTB Scanpix

100 Chinese Renminbi banknotes. Photo: Maksym Kapliuk/NTB Scanpix

Asylum seekers in Tijuana, Mexico, listen to names being called from a waiting list so that they can cross the border into San Diego. Photo: Elliot Spagat/AP Photo/NTB Scanpix

Asylum seekers in Tijuana, Mexico, listen to names being called from a waiting list so that they can cross the border into San Diego. Photo: Elliot Spagat/AP Photo/NTB Scanpix

Resettlement refugees

Although it is possible to provide good protection to most refugees in neighbouring countries if aid is stepped up, there are still some who must be moved to other countries as so-called “resettlement refugees”. These are typically refugees who do not receive adequate protection in the country to which they have fled. This may apply to religious minorities or LGBTQI+ people, for example.

In some instances, such as in Lebanon, recipient countries need relief following the arrival of large numbers of refugees. In cases where there is no prospect of the refugees being able to return to their homes within a few years, some must be given the opportunity to obtain permanent residency in a new country.

Countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia have not signed the Refugee Convention and expect refugees to remain only temporarily until they can be transferred to other countries as resettlement refugees. These must be taken away from the already very low number of resettlement refugees that Western countries have said they are willing to accept, at the expense of countries that have a far greater need for relief, such as Lebanon and Uganda.

According to UNHCR, in 2022 over 2 million people need to move as resettlement refugees to another country than the one they first fled to. This was an increase of 36 per cent from the corresponding figure one year previously. In 2022, only 114,000 resettlement refugees were able to start a new life in another country – less than six per cent of those waiting to become resettlement refugees.

If more countries were willing to accept resettlement refugees, it would be possible to find new homes for them within a few years. This would not represent a large burden for each individual country. In 2022, only 21 countries took in resettlement refugees, and many of these accepted only a symbolic number.

In recent years, Canada, Australia, Norway and Sweden have been the countries that have received the most resettlement refugees in relation to their populations. In 2022, these countries received 47,550, 17,325, 3,124 and 3,740 people respectively. Denmark, which previously received many resettlement refugees, has barely received any since 2016.

Syrian refugee Majda Ibrahim, 38, now lives in Skogas, Sweden. Photo: Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Syrian refugee Majda Ibrahim, 38, now lives in Skogas, Sweden. Photo: Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP/NTB Scanpix

The spiral towards the bottom

Denmark is one of the countries that has led the way in what has been called the “spiral towards the bottom”. This means that, as country after country tightens their refugee policies, displaced people choose to travel to another country instead.

When one country tightens its policies, other countries follow suit and introduce even stricter measures. And so the spiral continues – downwards. There are many examples of creative measures to deter refugees.

Denmark demands that refugees return to their home country as soon as possible, even if they have been in the country for many years. Denmark was the first country in the world to decide that even resettlement refugees must return to their home countries. In 2021, Denmark decided that it was now safe for most Syrian refugees from Damascus to return.

In 2021, it introduced a new immigration law that stipulates that asylum seekers who come to Denmark will be sent to countries outside Europe to have their asylum application processed. Those refugees who are granted asylum are not allowed to return to Denmark, but will receive protection in other countries. NRC’s Secretary General, Jan Egeland, called the Danish decision “a shocking example of the race to the bottom”.

The United Kingdom has followed Denmark’s example by entering into an agreement with Rwanda, which has promised to accept refugees who have fled to the UK. Unlike Denmark, which has not yet started sending refugees out of the country, the UK has made an initial attempt to send refugees to Rwanda, but the plane was stopped before it could depart following a decision by the European Court of Human Rights.

Norway was the first EU/EEA country to decide that refugees could be returned to a country outside the Schengen Area, even when it is not certain that their asylum applications will be processed there. The Norwegian government has also instructed the immigration authorities to actively review previous cases for refugees who have been granted refugee status in order to be able to revoke their status if conditions in their home country have improved. This applies to everyone who has not yet been granted permanent residency in Norway.

Hungary kept asylum seekers locked up in detention camps until The European Court of Justice ruled that this was illegal. In response, Hungary has made it impossible for people to seek asylum at the border. Like Bulgaria and Greece, Hungary has received criticism from the Council of Europe for pushing refugees back across the border when they try to seek asylum.

Since 2013, it has been impossible for boat refugees to receive asylum in Australia. Most boats with refugees are stopped by military ships and ordered to return to their point of departure.

Those who have managed to get to Australia have been sent to the island of Manus in Papua New Guinea and to Nauru, which have agreed to process asylum applications – for a fee. For a long time, the refugees were kept locked up in reception centres under inhumane conditions, but after strong international pressure, these centres were closed.

Some of the refugees have been allowed to travel to the United States as resettlement refugees, but there are still several hundred on Manus and Nauru. Some have also been transferred to detention centres in Australia. Australia’s policy has led to very few refugees now daring to seek asylum in the country without a visa, which for most is impossible to obtain.

Despite the great humanitarian suffering that this policy has inflicted on refugees and migrants, several European countries have called for the EU to follow Australia’s example. Denmark and the UK’s decision to send asylum seekers to countries outside Europe was strongly influenced by Australian policy.

Poland, Latvia and Lithuania have done everything they can to close their borders with Belarus to refugees and migrants. This happened after Belarus began using displaced people as a weapon in the conflict with the West in the summer of 2021.

The refugees and migrants themselves ended up in a desperate situation whereby they were unable to cross the border into the EU and unable to get out of the no man’s land between Belarus and its neighbouring countries. At least 24 people are said to have lost their lives. It is a clear violation of the Refugee Convention to deny people asylum at the border. The EU also has received criticism for tacitly accepting that EU countries are violating human rights at the EU’s external border.

Photo: Trygve Finkelsen/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Trygve Finkelsen/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Stefan Ember/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Stefan Ember/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Todor Dinchev/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Todor Dinchev/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Greg Balfour Evans/NTB Scanpix

Photo: Greg Balfour Evans/NTB Scanpix

This protest took place outside a hotel in Brisbane, Australia, on 15 August 2020 after media reports claimed asylum seekers were being detained there. Photo: Darren England/NTB Scanpix

This protest took place outside a hotel in Brisbane, Australia, on 15 August 2020 after media reports claimed asylum seekers were being detained there. Photo: Darren England/NTB Scanpix

When the pressure becomes too great

Even the countries that have long been most generous in accepting refugees have had to change their policies because so few other countries have been willing to share the responsibility. In Sweden, it took only a few months from when Prime Minister Stefan Löfven said: “My Europe does not build walls” to him announcing that Sweden had had to temporarily tighten its asylum policy to curb the influx of refugees.

One of the consequences was that Sweden began denying refugees the right to family reunification, even though they had already received subsidiary protection. This concerns people who have not been individually persecuted but who have fled due to war and violence.

Until 2016, this had had little practical significance, since both groups were largely given the same rights. But the change in the law meant that almost none of the Syrian refugees who had fled the civil war were given the opportunity to bring their families to Sweden. In 2019, this group was again given the right to family reunification.

Germany is another country that radically changed its refugee policy after more than one million people sought asylum in the country. Syrian refugees have been told that they must return to Syria when the war is over. Like Sweden, Germany also eliminated the possibility of family reunification for most Syrian refugees. Later, they introduced a monthly cap of 1,000 people who can receive visas for family reunification.

Poorer countries are the hardest hit

The poor neighbouring countries that have received millions of refugees are experiencing even greater pressure than countries such as Sweden and Germany.

Many of the countries receiving the largest number of refugees have not signed the Refugee Convention, meaning the refugees there have less protection. This applies to countries such as Bangladesh, Lebanon and Jordan, while Turkey made an exception when they ratified the convention so that it only applies to refugees from Europe.

Mhammad is a Syrian refugee living in Bekaa, Lebanon. In January 2019 he was forced to sleep in a school after his tent flooded. Photo: Nadine Malli/NRC

Mhammad is a Syrian refugee living in Bekaa, Lebanon. In January 2019 he was forced to sleep in a school after his tent flooded. Photo: Nadine Malli/NRC

For Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey, the large number of Syrian refugees has led to internal tensions. The refugees in these countries have little access to the regular labour market and often have to make do with underpaid jobs and informal employment. This means that wages are pushed down, and fewer jobs are available to the country’s own population.

This affects the refugees most of all. They must live on a subsistence level, while also experiencing hostile attitudes.

Not an impossible task

Most people flee to a neighbouring country, and with sufficient financial support from rich countries in the rest of the world, it is in many cases possible to safeguard their protection. Unfortunately, there is a lack of willingness to increase aid in step with the increasing number of people who need help.

Compared to other expenses afforded by rich countries, only a pittance is needed to ensure that displaced people receive the help they need. This has been clearly illustrated in connection with the Covid-19 pandemic.

For every dollar that wealthy countries have spent supporting their own economies during Covid-19, they have given less than ½ a cent in emergency aid to the 250 million people who need it most.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) works to support refugees and displaced people worldwide. Support our work today.