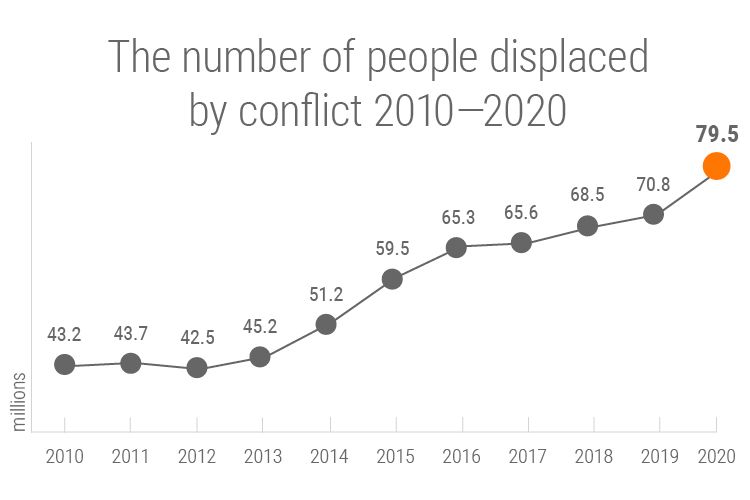

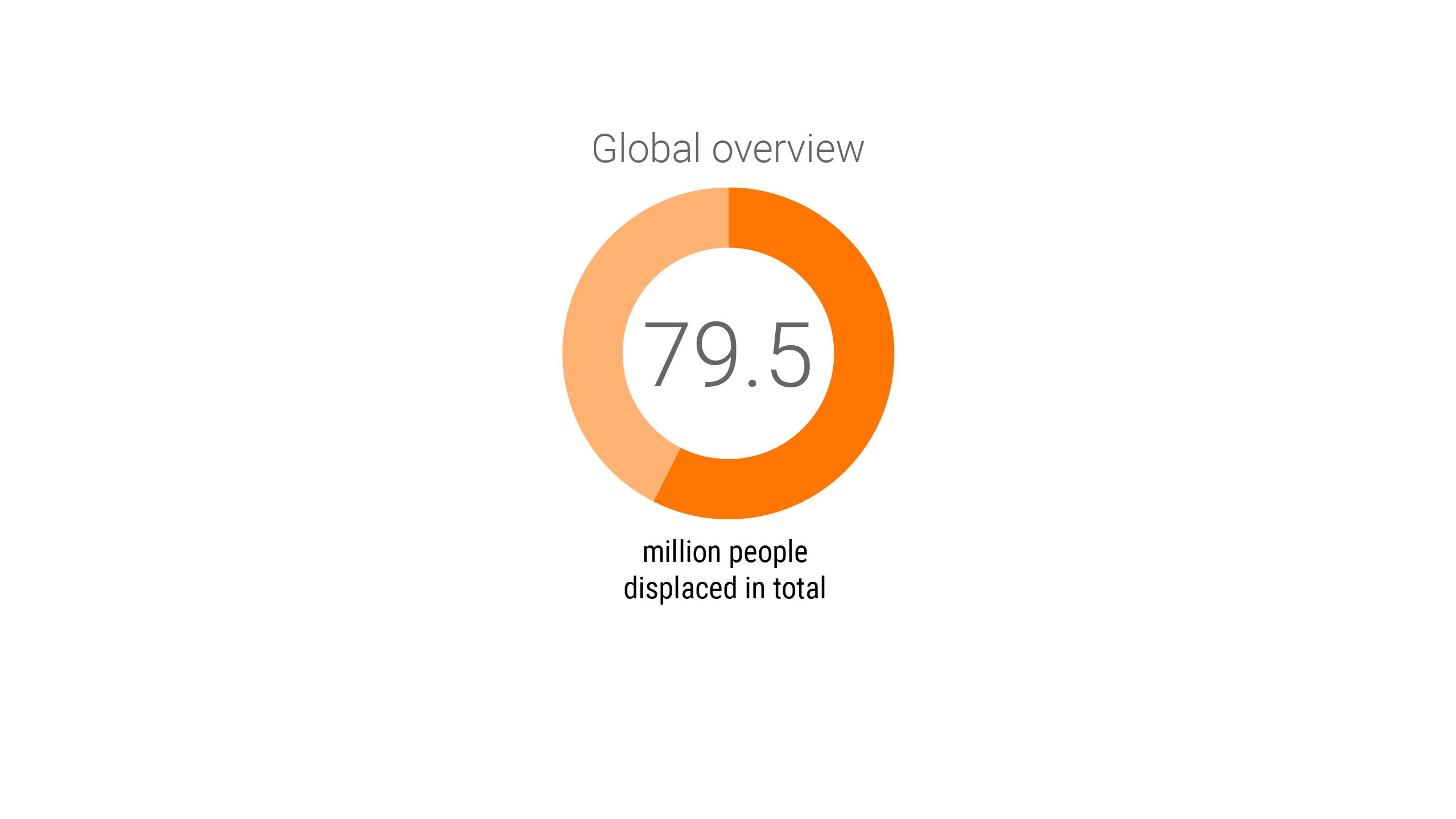

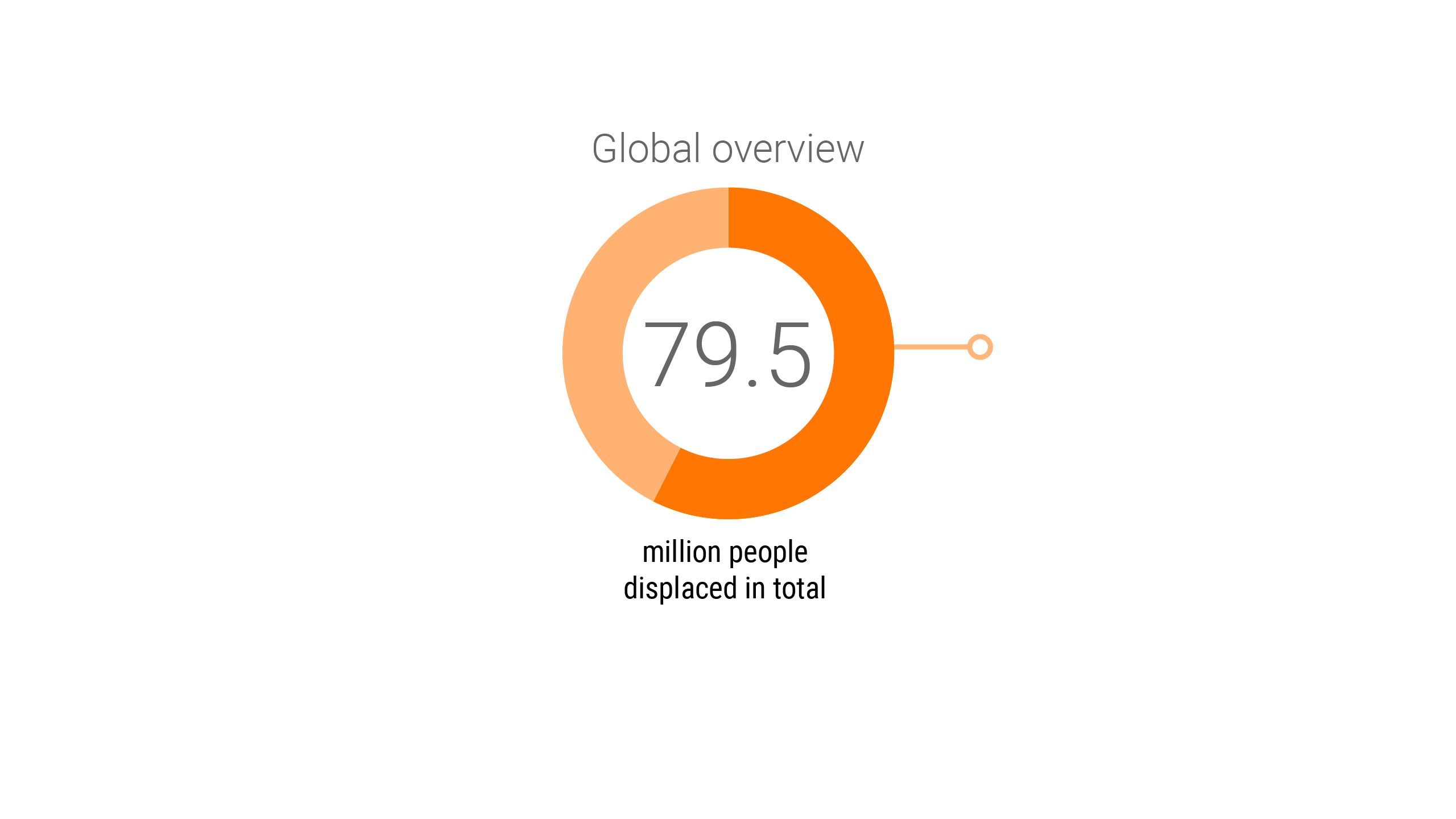

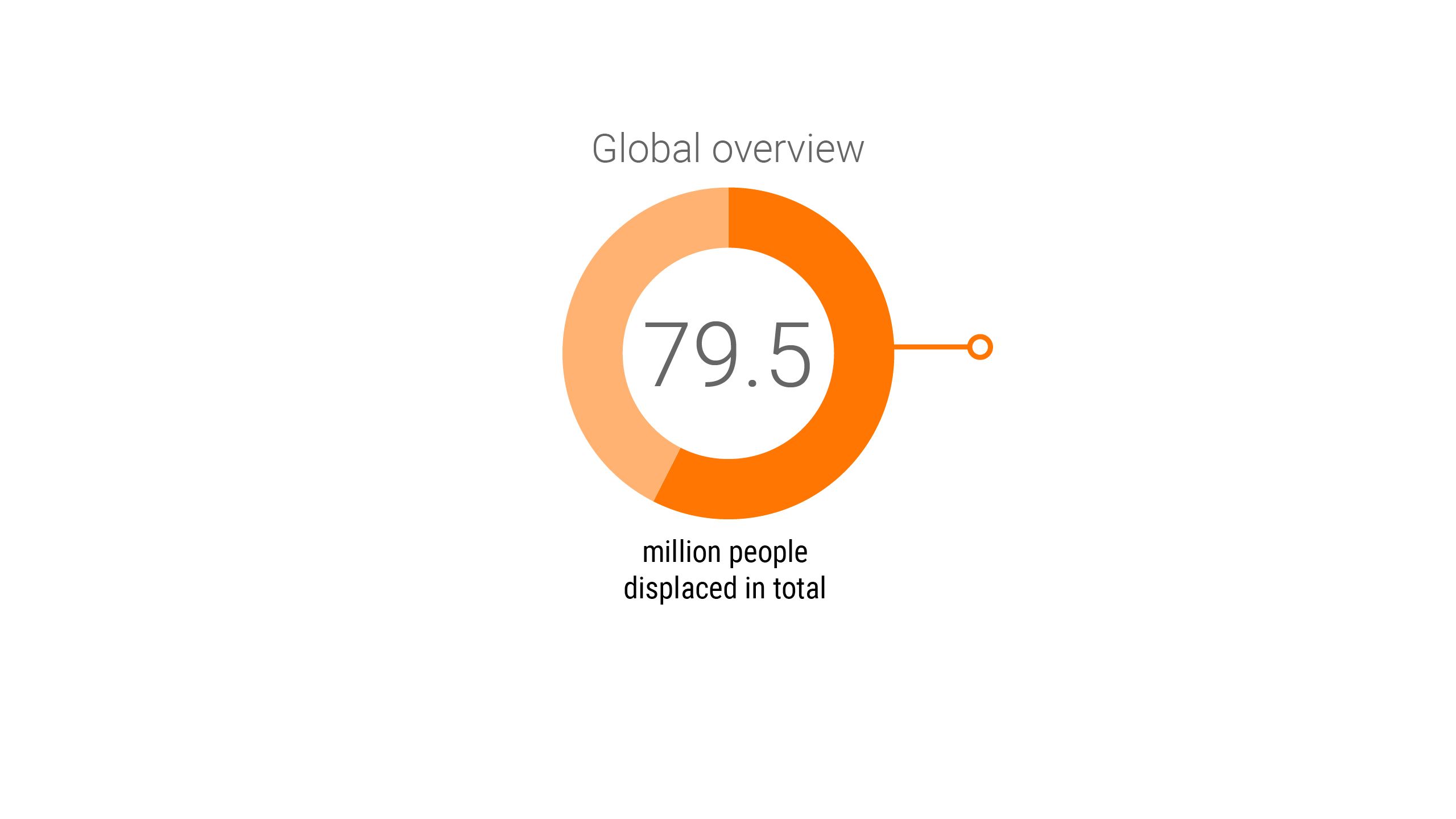

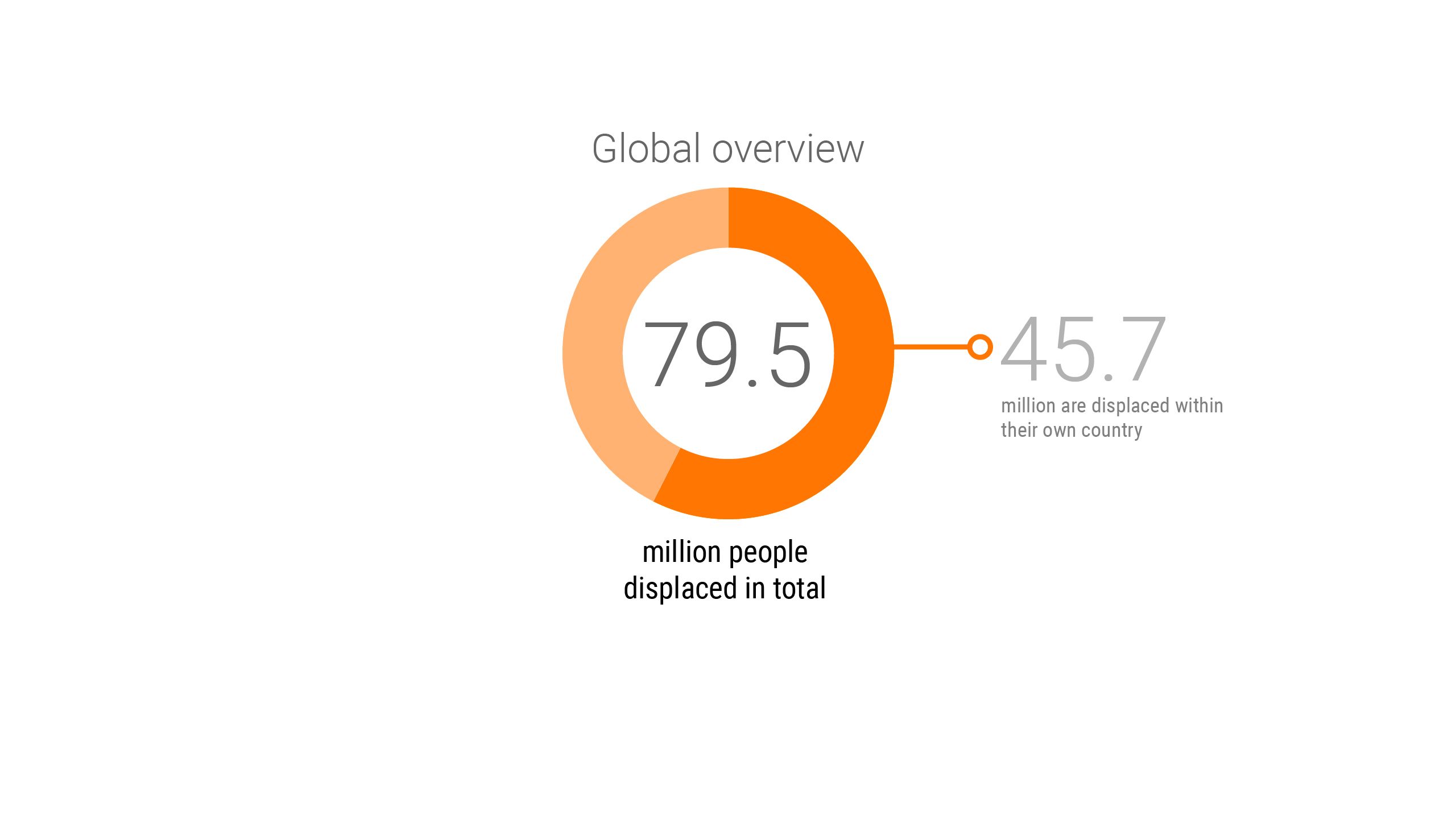

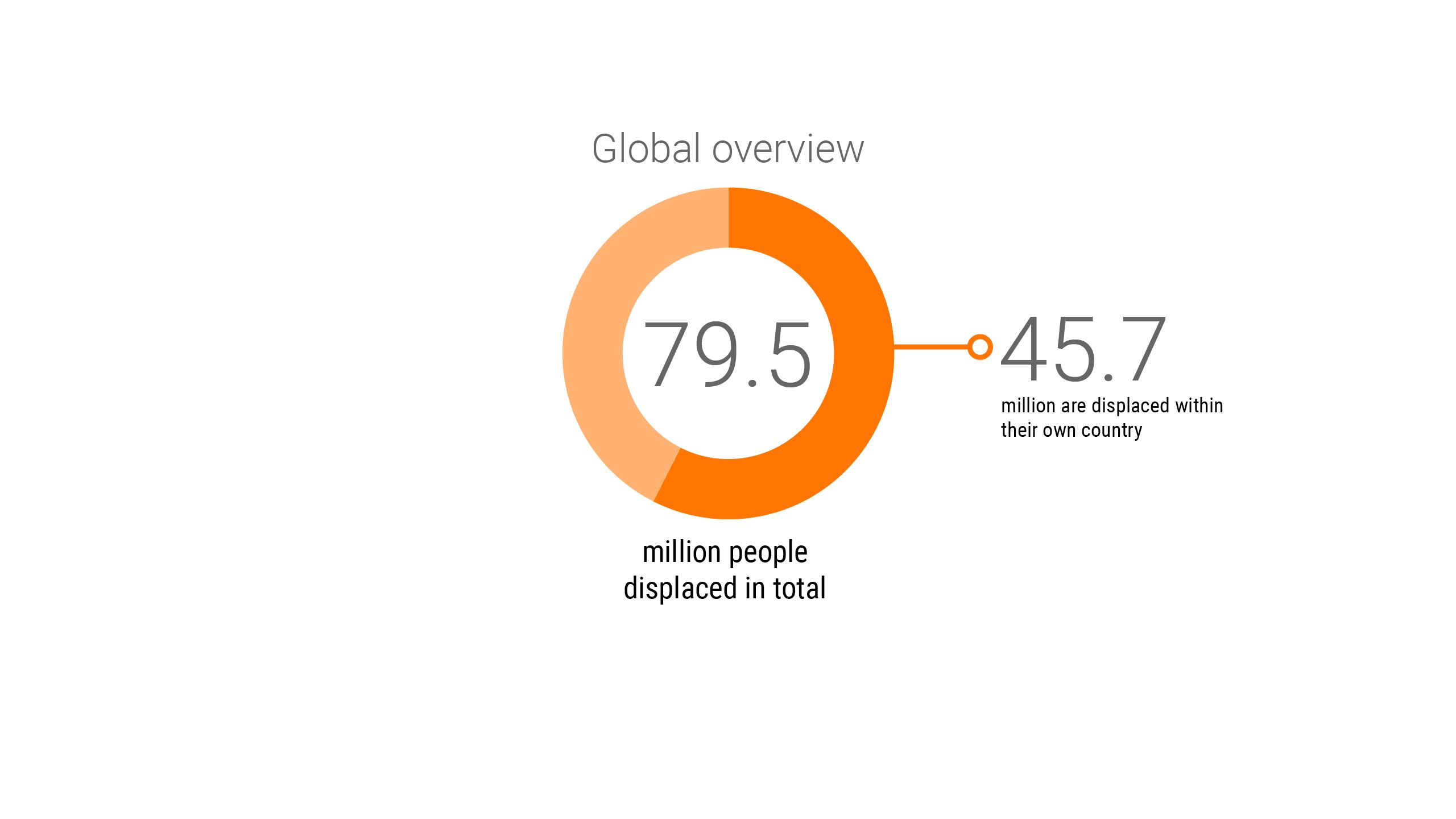

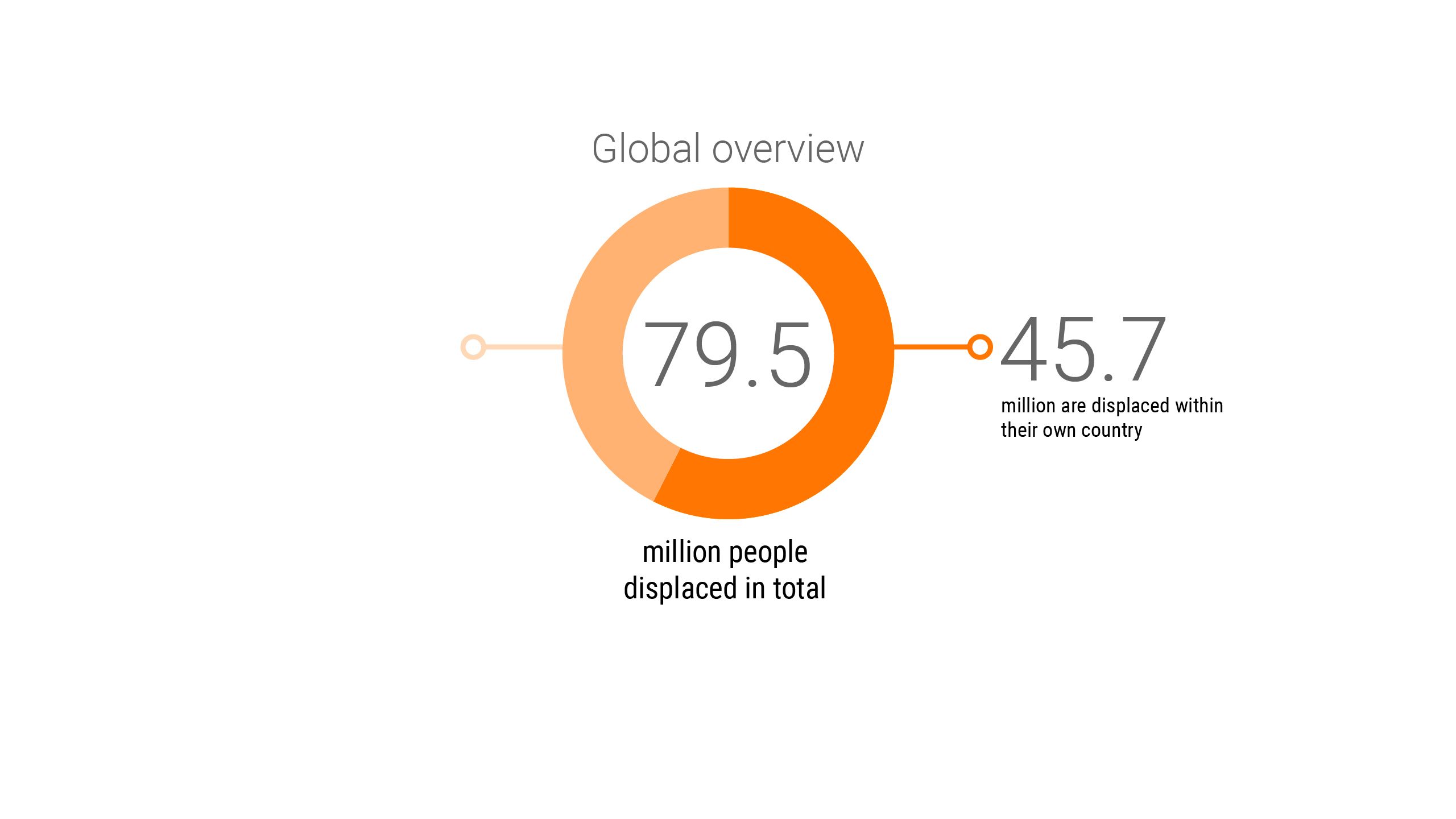

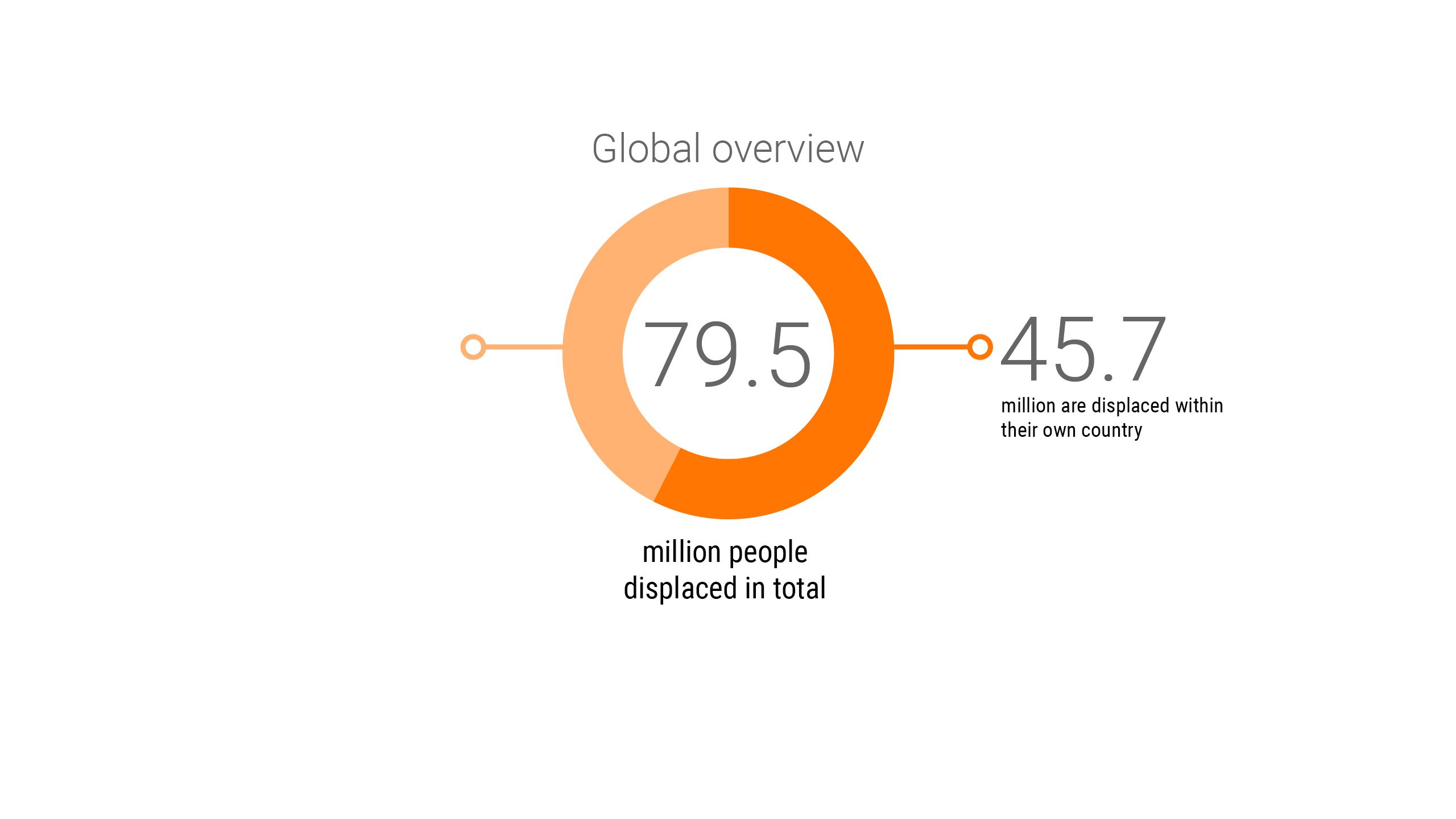

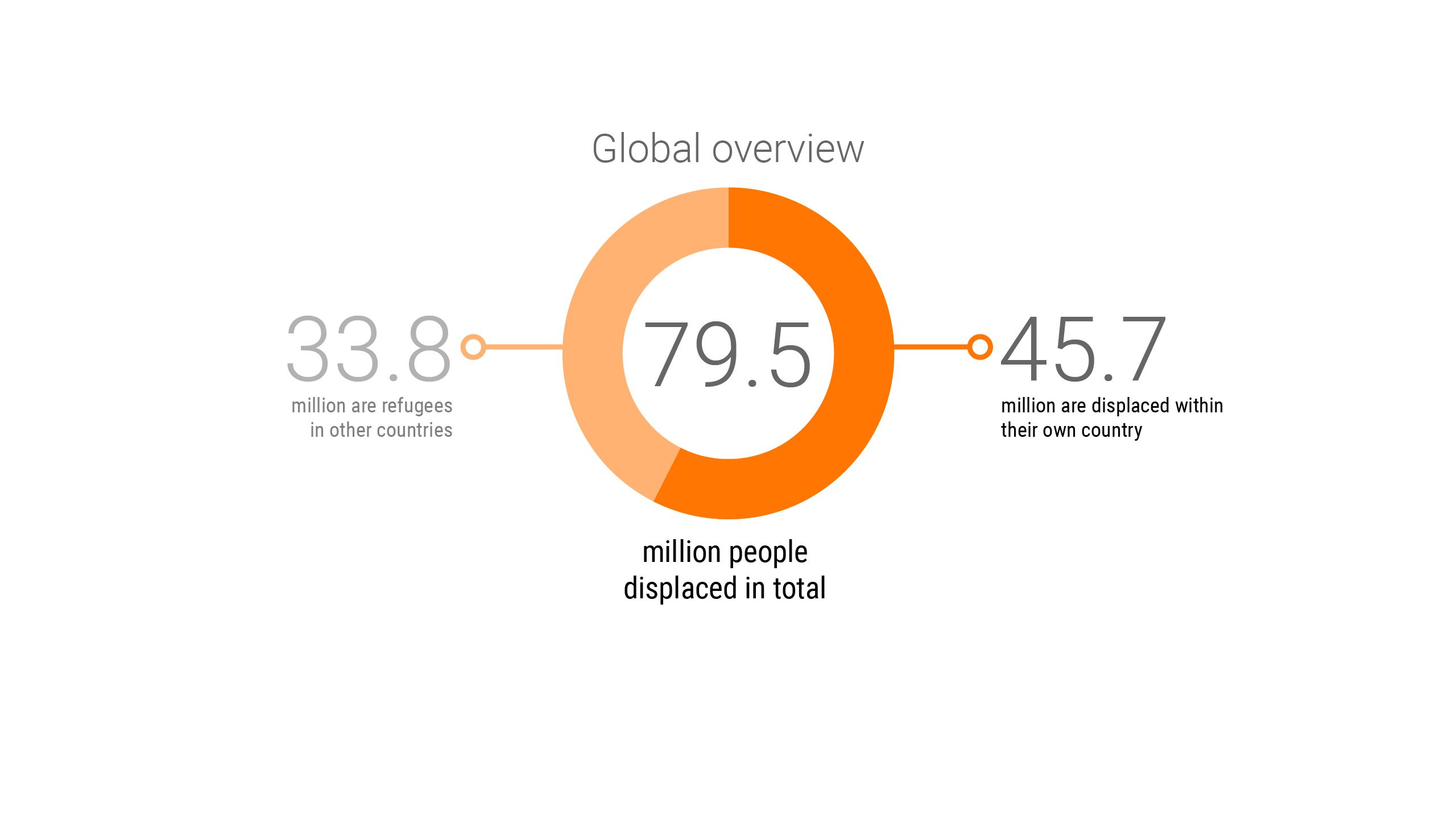

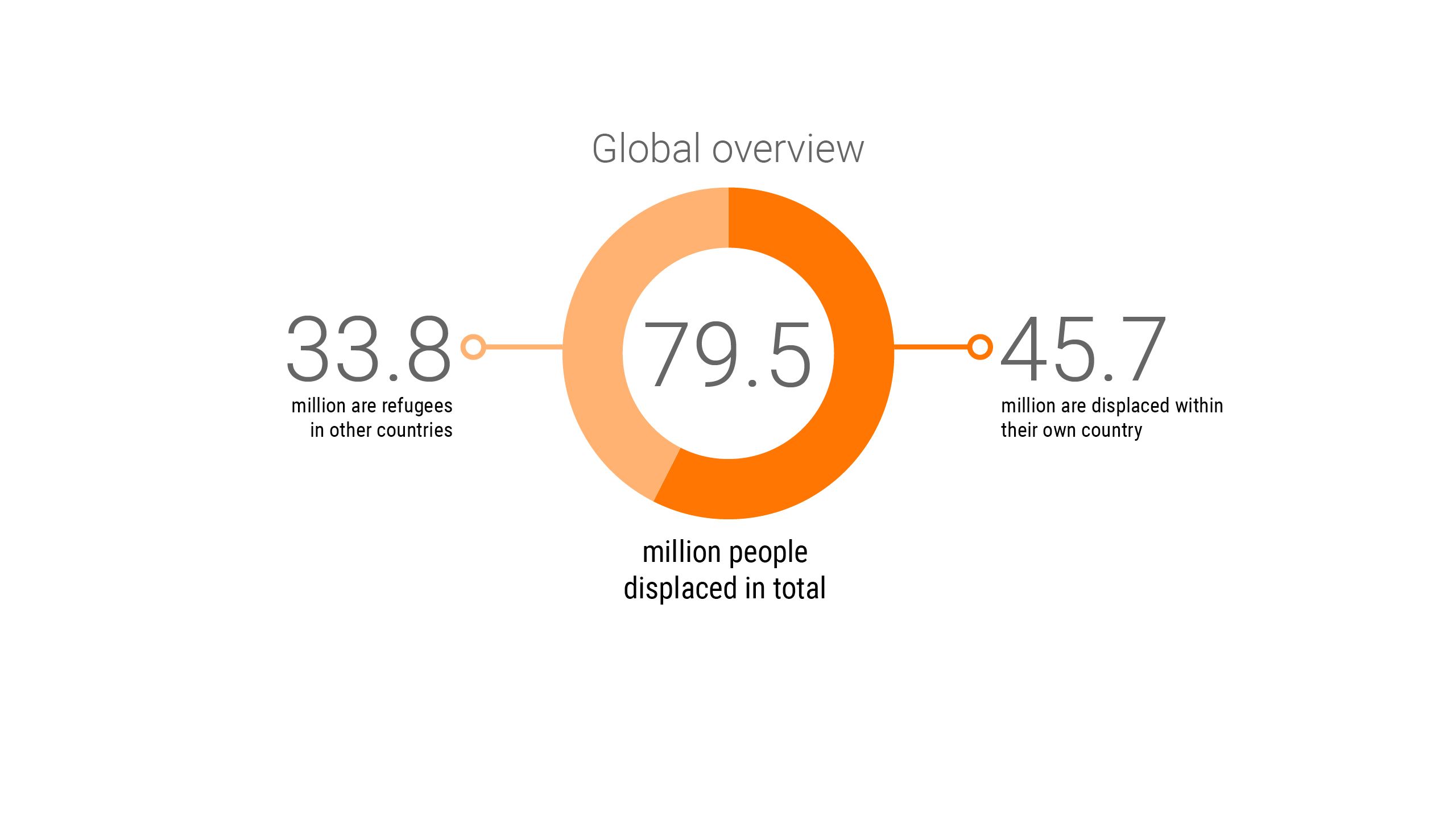

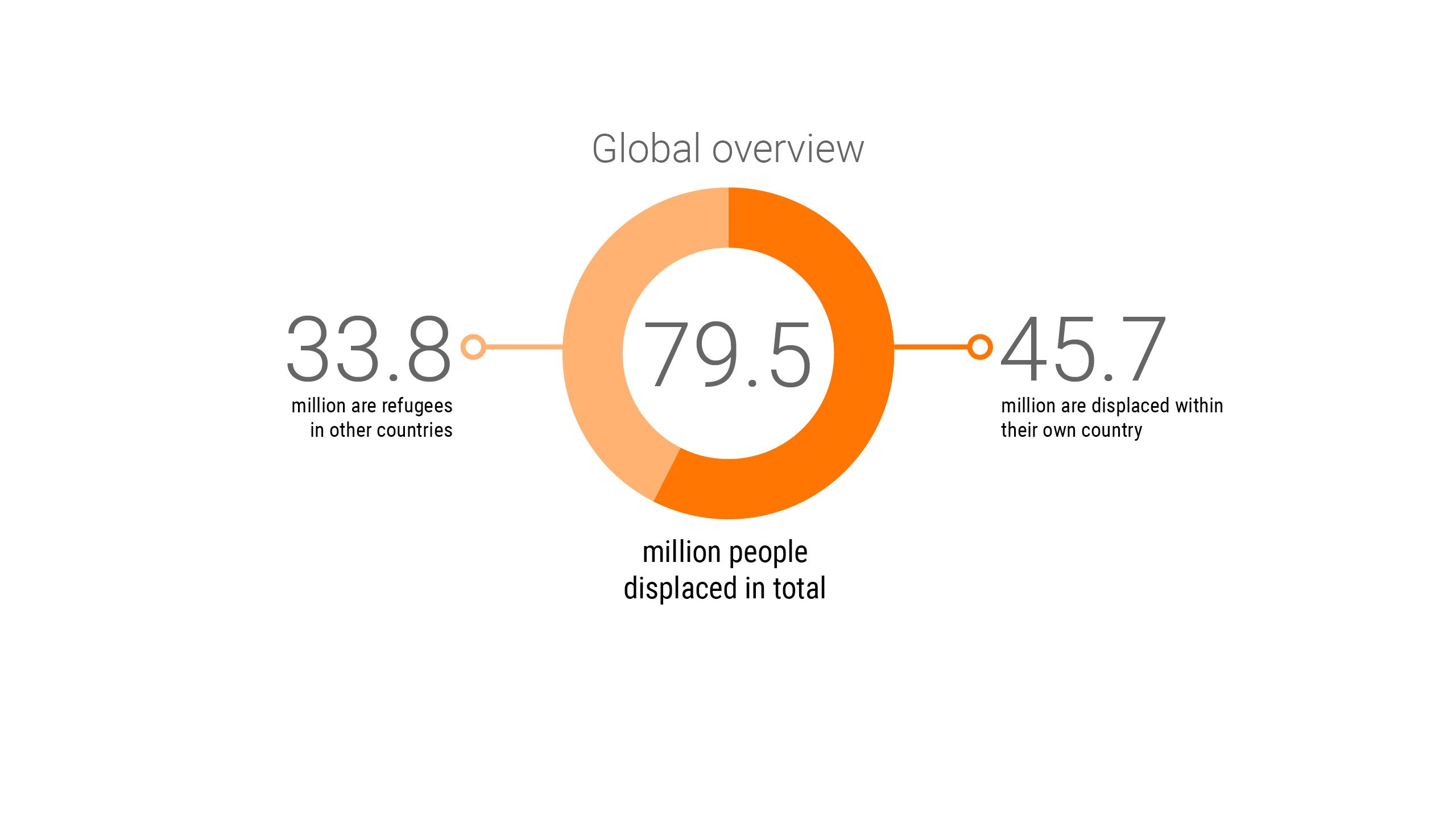

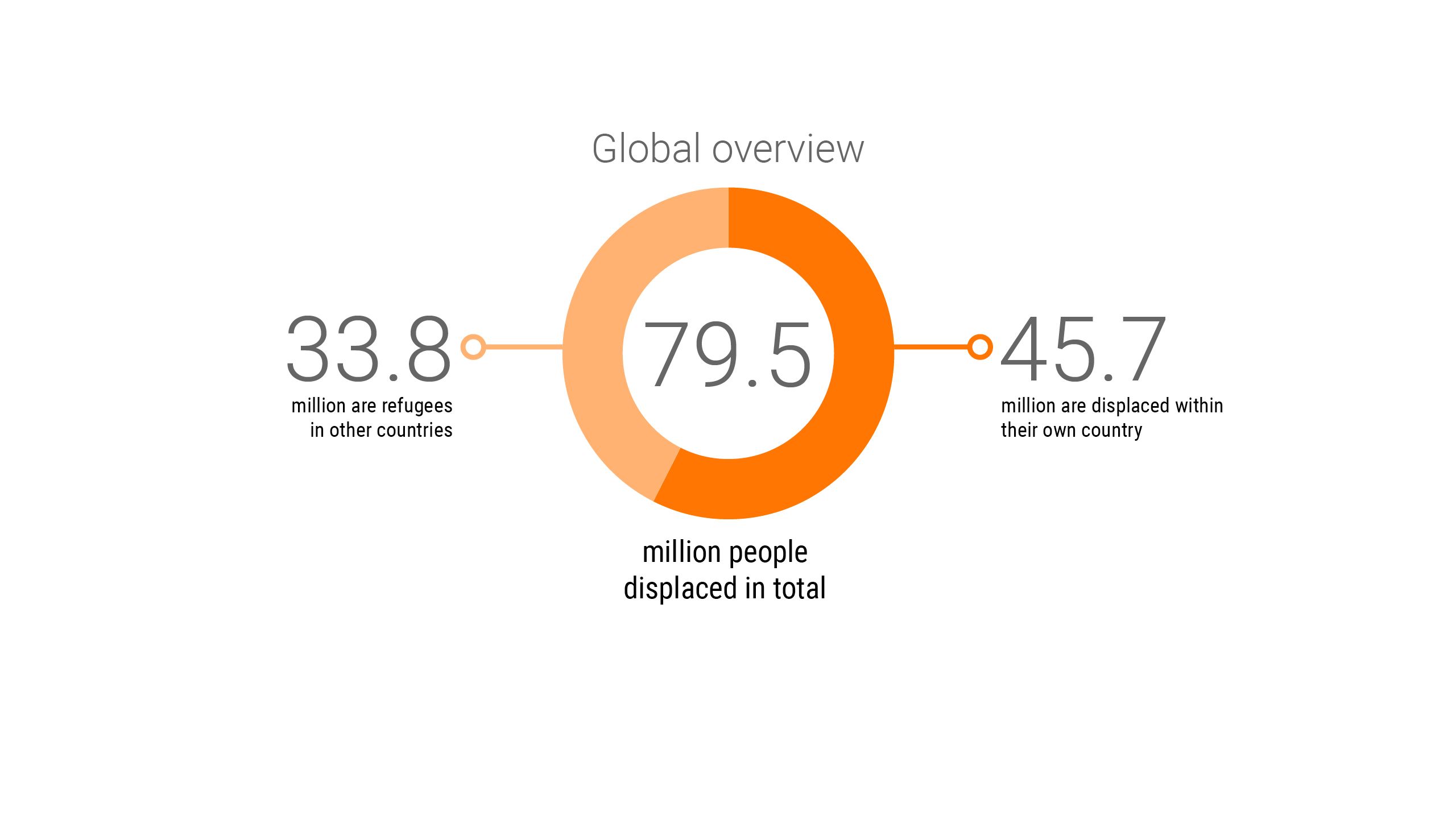

79.5 million people displaced in the age of Covid-19

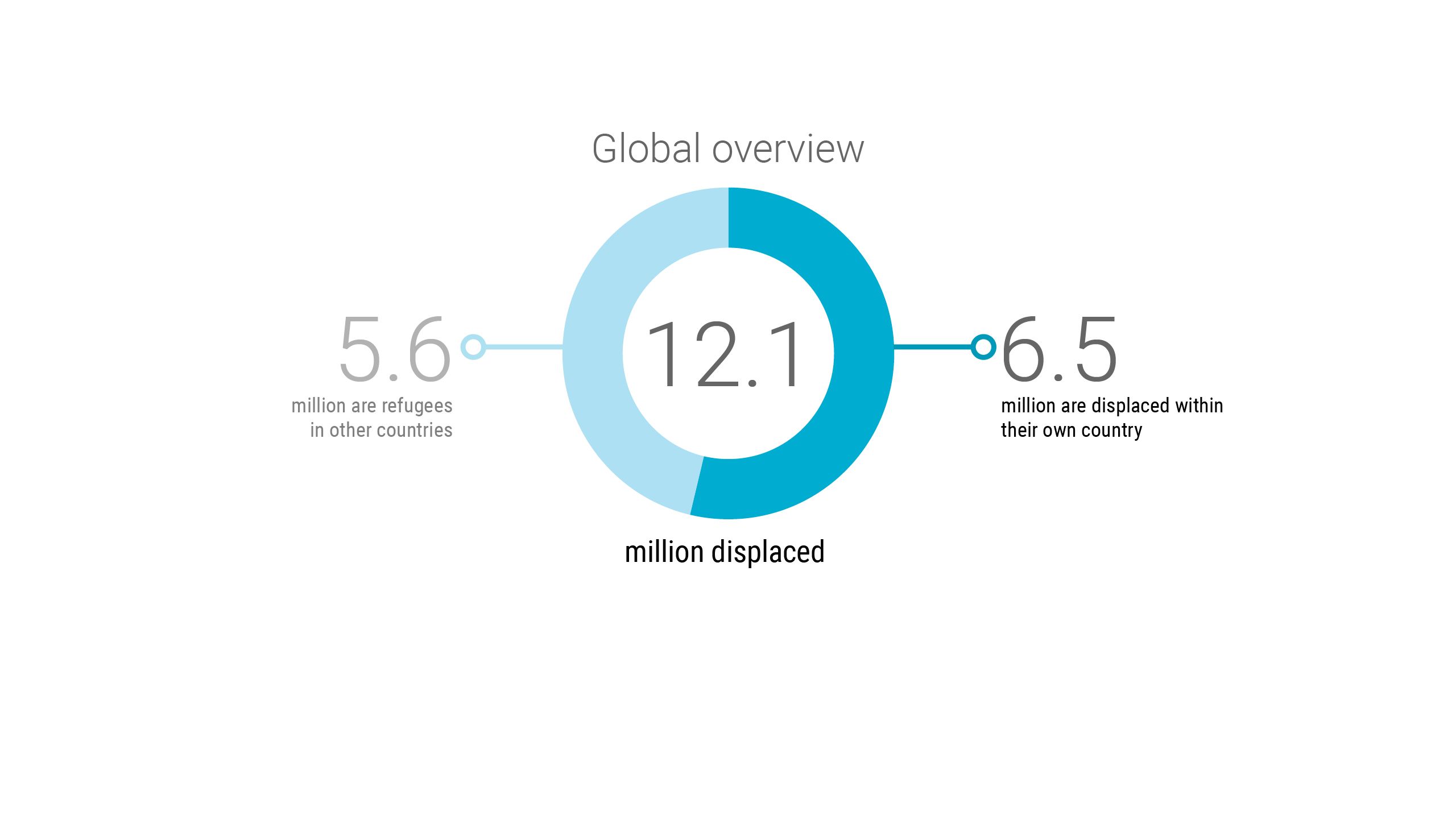

A global overview of displacement crises in 2019

As we entered 2020,

79,500,000

people were displaced by persecution and conflict.

The number of people fleeing from war, conflict and persecution has risen for the eighth year in a row. The fate of nearly 80 million people should concern us all, but the help they receive is far from sufficient to meet their needs. In addition, an invisible enemy has emerged: Covid-19.

The world held its breath during the winter and spring of 2020. A new virus emerged and quickly had global consequences, turning the world upside down in a matter of weeks. In May 2020, infection rates finally began to decline in Europe. Meanwhile, rates started rising in many less wealthy countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

Figures as per 31 December 2019. Source: UNHCR/UNRWA/IDMC

Figures as per 31 December 2019. Source: UNHCR/UNRWA/IDMC

We have all been told the necessity of good hand hygiene and social distancing. But these are impossible tasks in crowded refugee camps in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Greece – where many people live in a small area, with poor health services and sanitary conditions.

We do not yet know what the long-term consequences of the pandemic will be.

A crisis long before the pandemic

Displacement crises have been happening for as long as we can remember. The fact that refugees are drowning, are being exploited by traffickers or are succumbing to neglect and unworthy treatment in crowded camps is something we have heard so often that we have come to think of it as normal.

But the world must not become a place where we fail to hear people’s despondent cries in Libyan detention centres. Or a place where we simply overlook desperate people fighting a daily battle to survive on the US-Mexico border.

Displaced people need more than just words and quiet sympathy. They need a system that works and politicians who dare to stand up for them.

Lack of help has deadly consequences

Poor and vulnerable countries are often unable to provide their citizens with basic services. If a conflict arises, many of those who are forced to flee will be left with nothing. A number of poor countries also welcome large numbers of refugees from conflict-affected neighbouring countries, such as those of the Sahel region of Africa.

For refugees and internally displaced people in these areas, the situation is not only difficult, it’s critical.

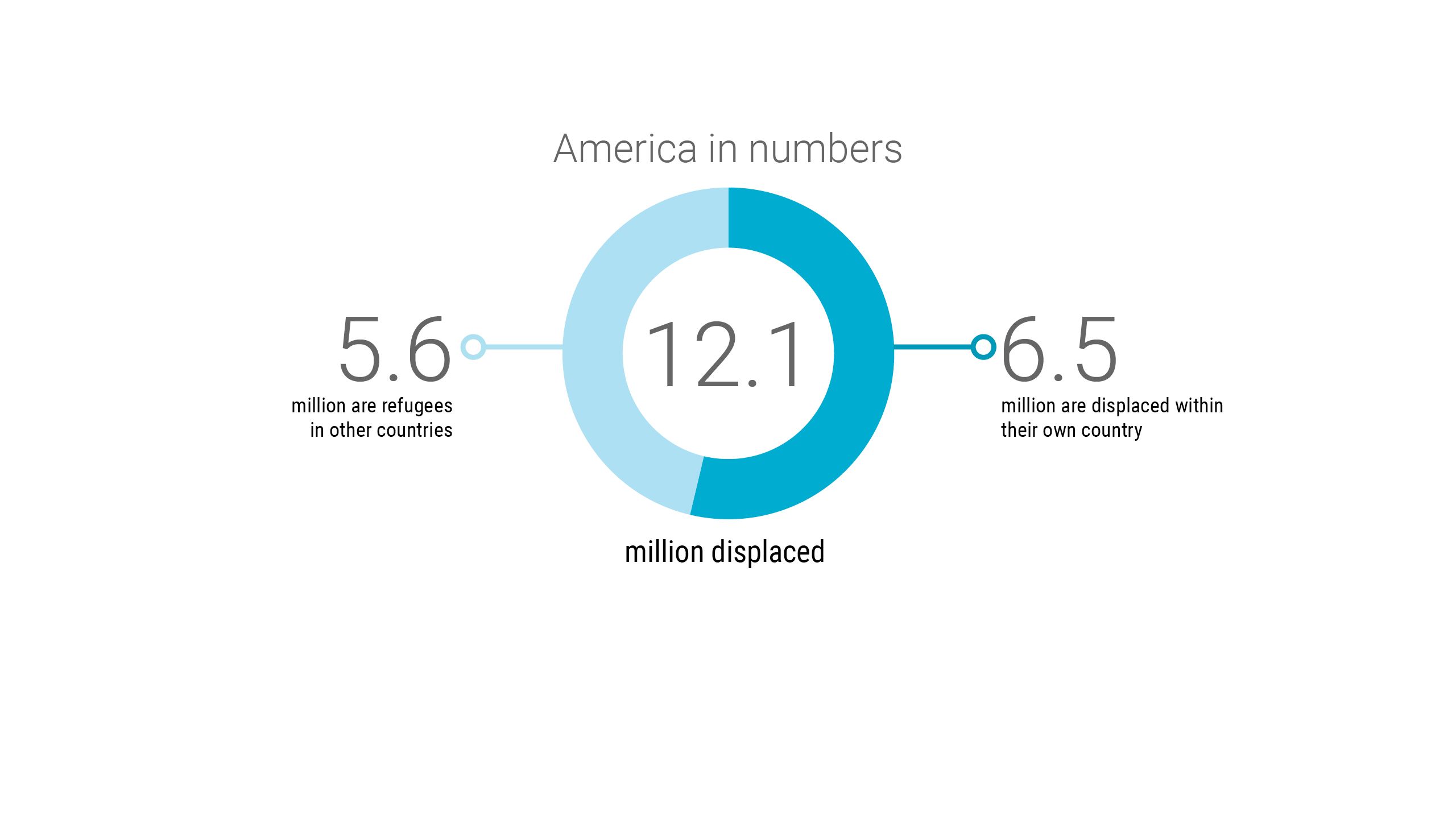

Figures as per 31 December 2019. Source: UNHCR/UNRWA/IDMC

Figures as per 31 December 2019. Source: UNHCR/UNRWA/IDMC

In February 2020, the UN announced that there was an increased need for emergency aid due to prolonged armed conflicts and more extreme weather. This is not only because the number of displaced people is now higher than ever recorded, but also because the gap between funds needed and funds pledged for emergency aid is still huge.

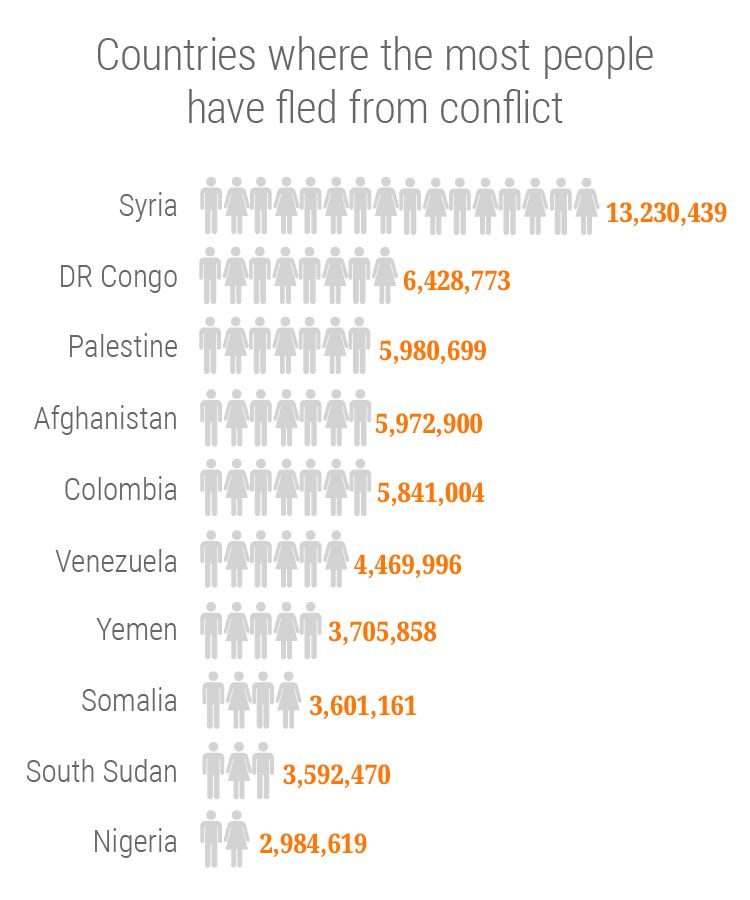

This is a global challenge, but has particularly affected African crises such as those in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), Cameroon, Burkina Faso and Burundi.

Families wait by the side of the road after fleeing attacks in Burkina Faso. The number of displaced people increased to over half a million last year, and the country is on the brink of a hunger crisis. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

Families wait by the side of the road after fleeing attacks in Burkina Faso. The number of displaced people increased to over half a million last year, and the country is on the brink of a hunger crisis. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

In the last six years, only around 60 per cent of the money required for humanitarian appeals has been raised. The consequences have been fatal. Lack of political will, scarce resources and insufficient diplomacy have forced millions of people from their homes and into a highly uncertain future. These people lack food, water, education and – not least – protection.

In the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, world leaders declared that they would share the responsibility of protecting and supporting refugees and displaced people. Since that time, borders have been closed to families in need of protection. The number of resettlement refugees has been reduced and poor host countries have been left with little international support.

If we are to save a refugee system that is in danger of collapsing, this trend must be reversed.

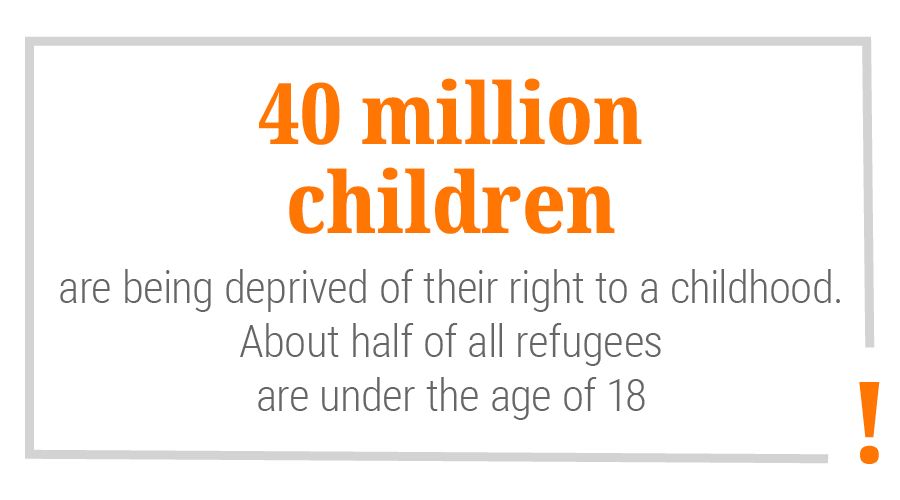

According to UNHCR, half of the world's refugees are estimated to be under the age of 18. A similar estimate can be made for internally displaced children.

According to UNHCR, half of the world's refugees are estimated to be under the age of 18. A similar estimate can be made for internally displaced children.

Politicians around the world often talk about children and their rights. But for millions of refugee children, those words are empty because resources are lacking.

Read more: Sara was to be married – at the age of seven

The vultures pick on the most vulnerable

Protection is a necessary cornerstone of international refugee work. On a daily basis, people are exploited and subjected to abuse and forced labour by cynical traffickers.

Many of the world’s countries are experiencing the effects of large numbers of migrants and refugees, either as countries of origin, transit countries or host countries. Sometimes these effects are felt in combination, for example in parts of Latin America. Desperate displaced people and unaccompanied children are especially vulnerable to ending up in the clutches of criminal networks through people smuggling and human trafficking.

Drug trafficking, arms smuggling, human trafficking and people smuggling are all billion-dollar industries. They contribute to destabilising vulnerable countries, displacing people and funding armed groups.

These challenges are especially visible in Colombia and Central America. Most of the victims of organised crime are young people, many of whom have been forced to flee their homes. They may use drugs, be recruited into criminal gangs, or become child soldiers or sex slaves. The vultures pick on the most vulnerable.

Civilians and humanitarian aid workers in the line of fire

Most of the conflicts around the world today take place within a country rather than between countries. Consequently, the number of internally displaced people is far higher than the number of refugees, who by definition have crossed an international border.

Internal conflicts often have no frontlines and involve many different armed actors. This makes the civilian population highly vulnerable to attacks, while also posing a major security challenge for humanitarian aid workers.

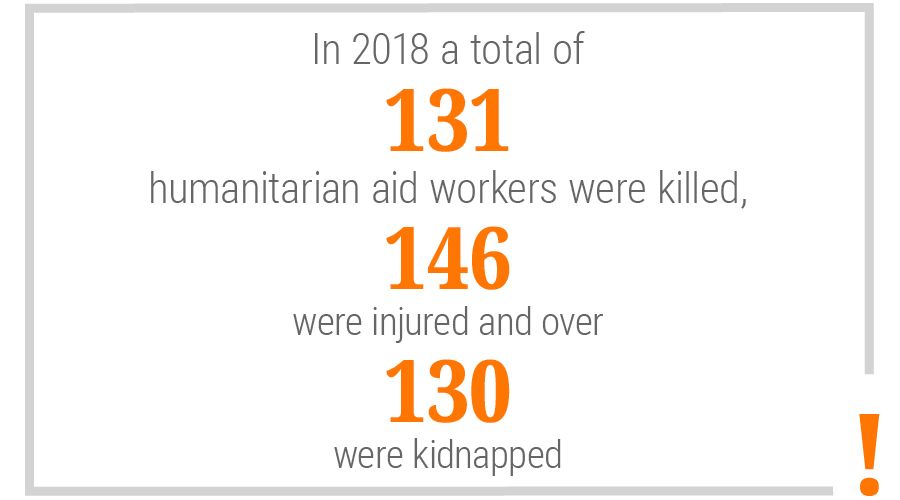

In 2018 a total of 131 humanitarian aid workers were killed, 146 were injured and 130 were kidnapped, according to the Aid Worker Security Database.

In 2018 a total of 131 humanitarian aid workers were killed, 146 were injured and 130 were kidnapped, according to the Aid Worker Security Database.

In a country such as the Central African Republic (CAR), 70 per cent of the land is outside government control. Aid organisations must negotiate with various armed groups in order to provide assistance to displaced people in the areas controlled by these groups. This is also the case in many other conflict zones.

Criminal gangs murdered 35-year-old “Oscar’s” brother five years ago. He has tried to leave Honduras six times since 2018 due to death threats but has been deported from both the United States and Mexico. Photo: NRC

Criminal gangs murdered 35-year-old “Oscar’s” brother five years ago. He has tried to leave Honduras six times since 2018 due to death threats but has been deported from both the United States and Mexico. Photo: NRC

Shelling hits IS group’s last holdout of Baghouz in the Syrian civil war. Humanitarian aid workers put their lives at risk every day to help civilians in war and conflict zones. Photo: Delil Souleiman/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Shelling hits IS group’s last holdout of Baghouz in the Syrian civil war. Humanitarian aid workers put their lives at risk every day to help civilians in war and conflict zones. Photo: Delil Souleiman/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Starving Rohingya refugees are rescued in the Bay of Bengal in April 2020. The UN has described the Rohingya population as the world’s most persecuted people. Photo: Suzauddin Rubel/AP/NTB Scanpix

Starving Rohingya refugees are rescued in the Bay of Bengal in April 2020. The UN has described the Rohingya population as the world’s most persecuted people. Photo: Suzauddin Rubel/AP/NTB Scanpix

Xaliimo is helping her mother-in-law rebuild her house ahead of the stormy season in a camp outside Garowe, Somalia. The family fled their drought-affected home more than a year ago. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Xaliimo is helping her mother-in-law rebuild her house ahead of the stormy season in a camp outside Garowe, Somalia. The family fled their drought-affected home more than a year ago. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Inequality creates conflicts

Inequality and the marginalisation of certain groups of people are key contributing factors to conflicts. This is a global phenomenon that is prevalent in such diverse areas as Myanmar, Afghanistan, large parts of the Middle East, the Sahel region of Africa and Colombia.

Situations can become particularly precarious when inequality runs along ethnic and religious divisions, and the authorities do not have the political will or capacity to address the issue before violence erupts. This type of conflict, in which an entire group is defined as an enemy, hits the civilian population especially hard.

Displaced by climate change

Extreme weather and disasters displace millions of people each year, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

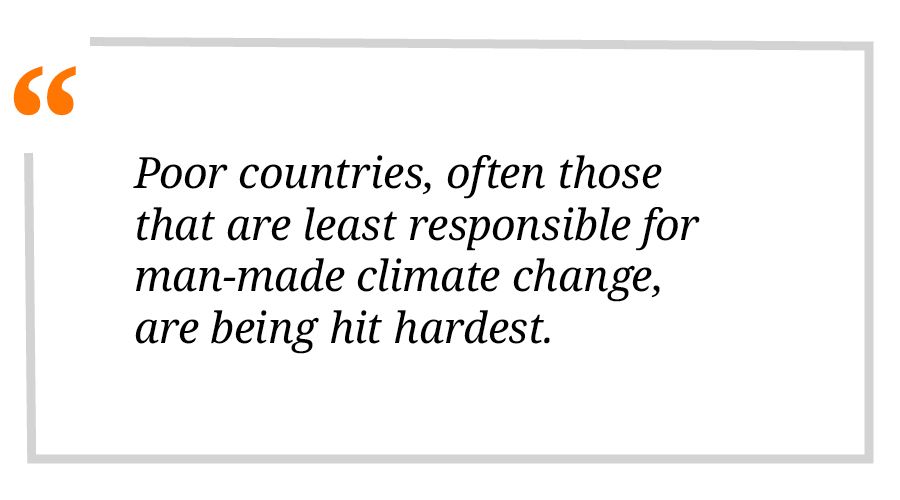

These people fall outside the official statistics of displaced people because they are not displaced by war, conflict or persecution. Poor countries, which are often those least responsible for man-made climate change, are being hit hardest.

The UN’s Global Compact for Migration, published in December 2018, is the first comprehensive UN document in which the global community commits to focus on disasters and climate change as reasons for why people flee across borders. However, the compact will only live up to its potential if countries implement concrete measures.

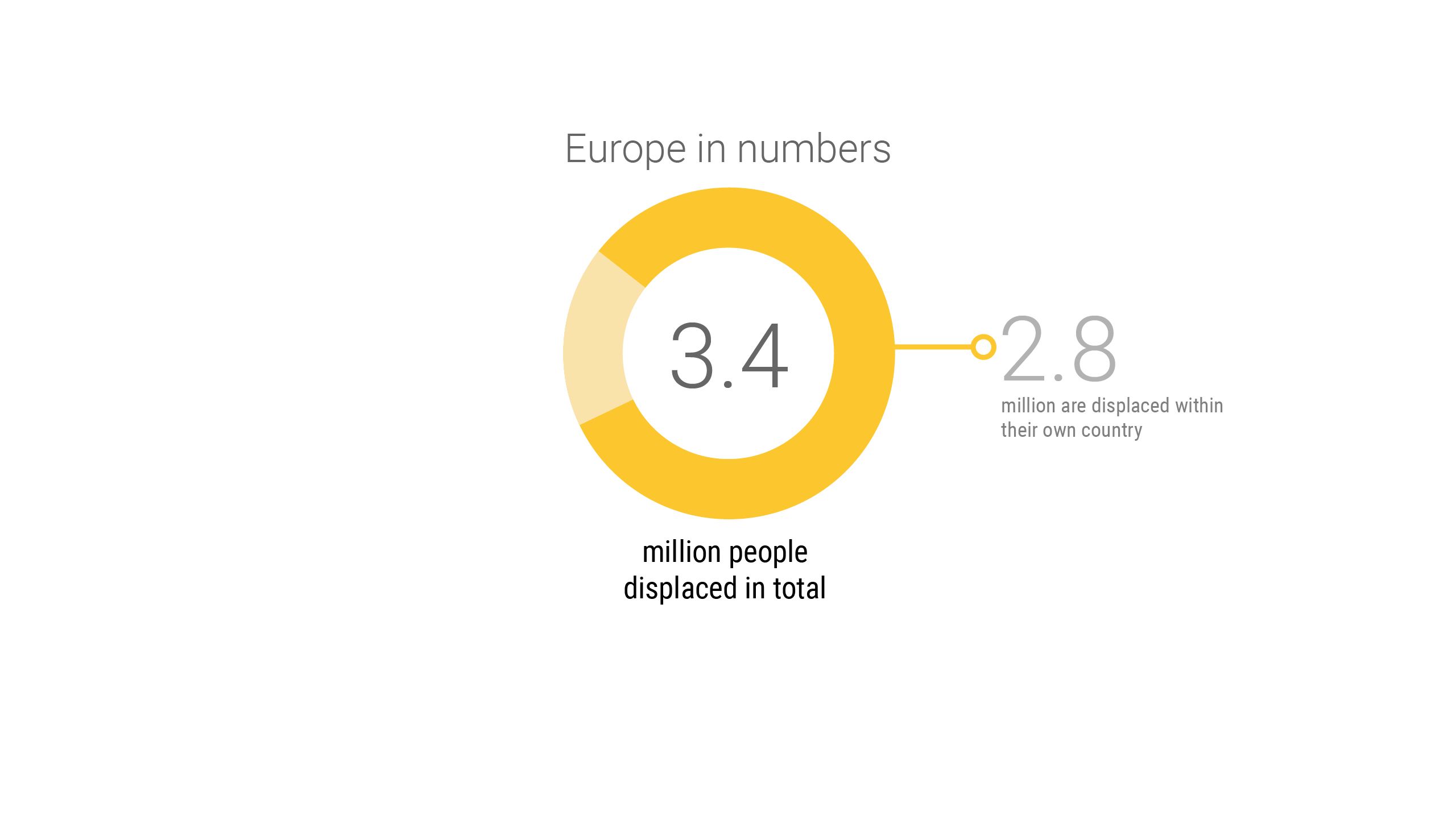

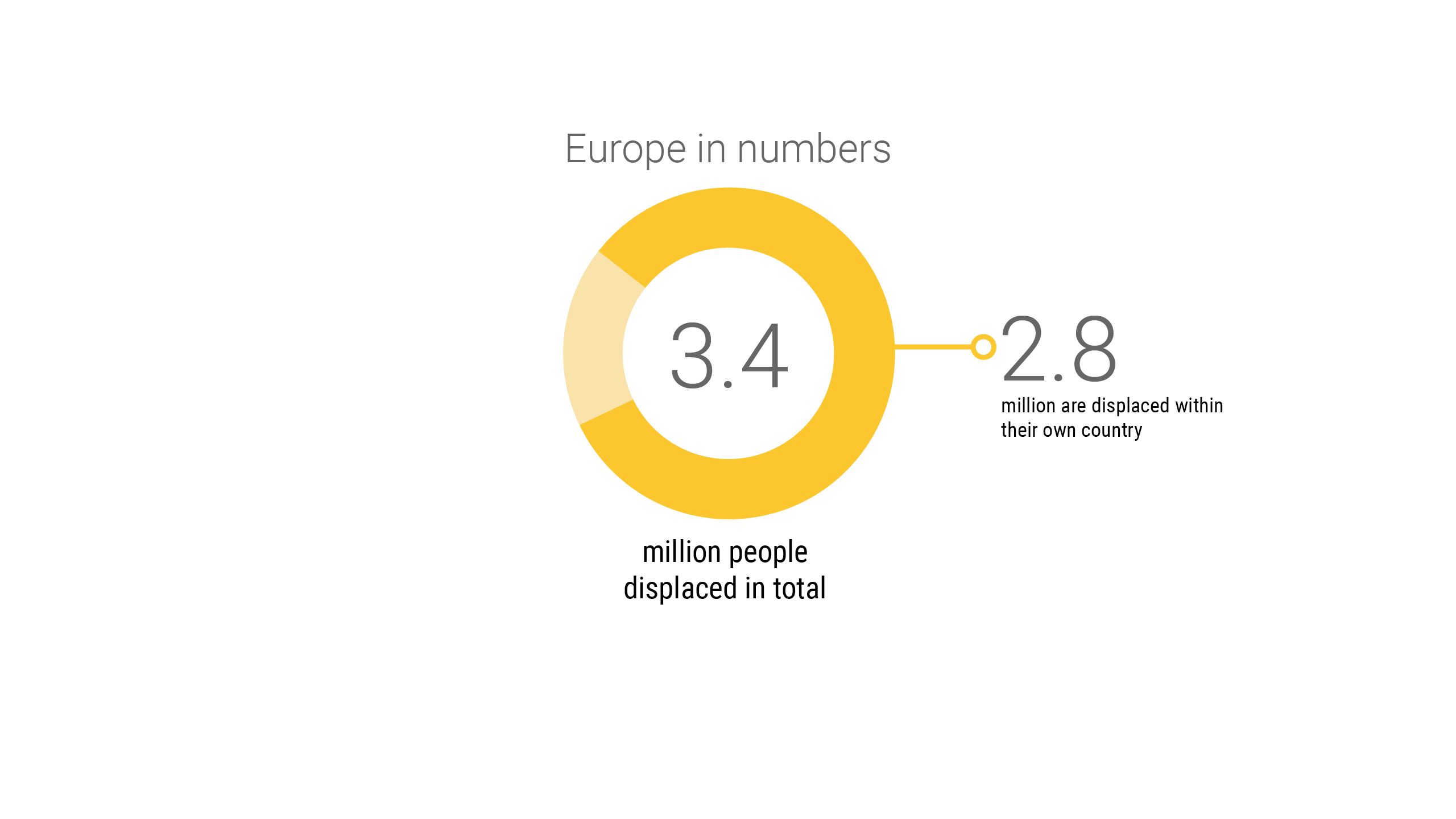

Poor division of responsibility

European refugee policy has been in a state of paralysis for several years. Closed borders, a lack of funds and insufficient relief efforts are forcing both desperate families and unaccompanied children to resort to dangerous survival strategies.

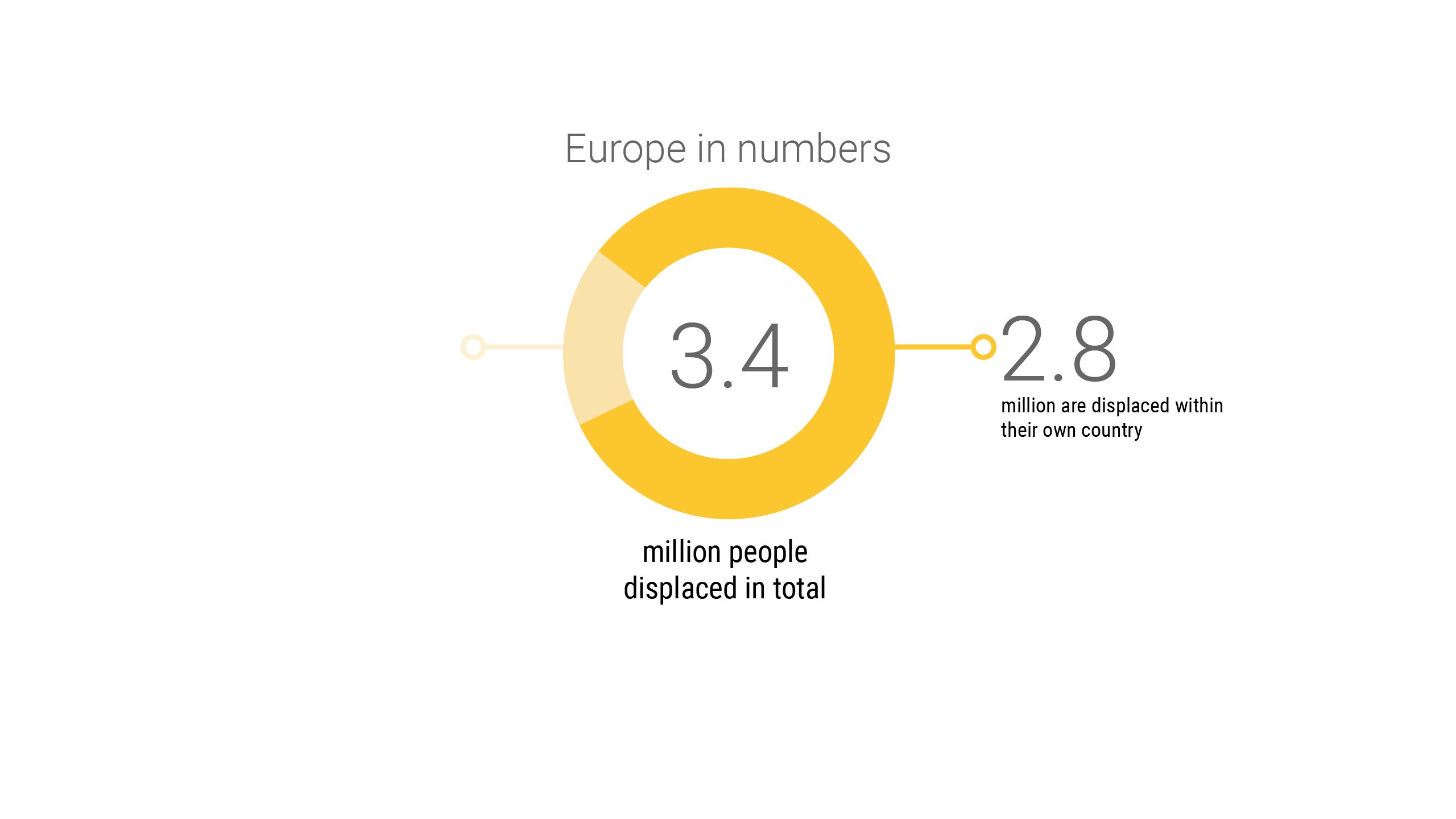

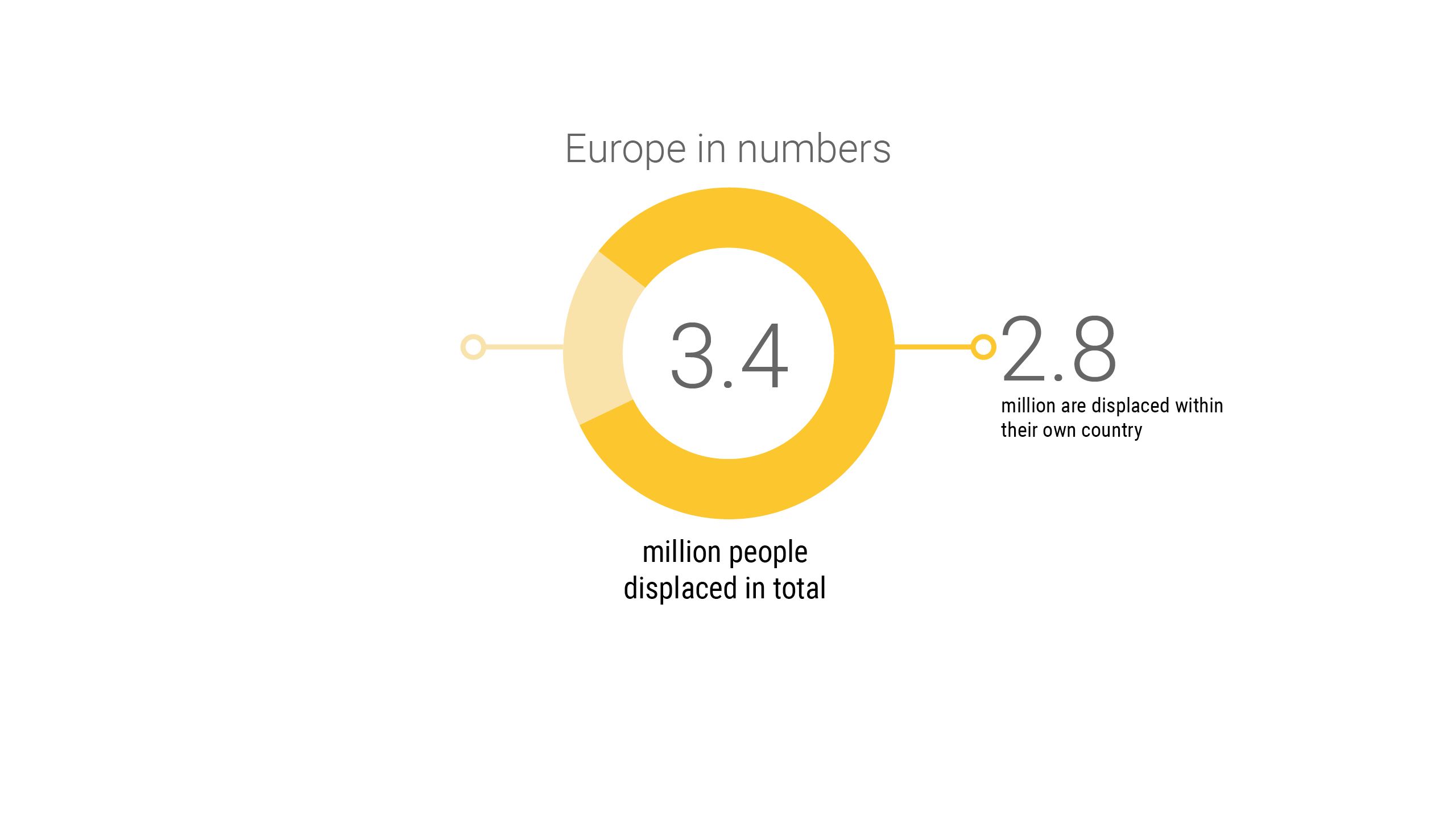

Source: UNHCR.

Source: UNHCR.

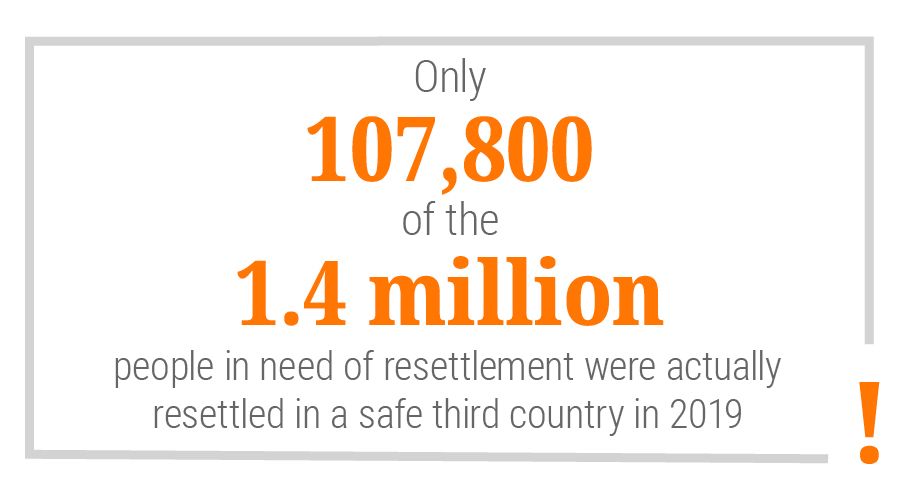

Although the number of people resettled in a safe third country is slightly higher than the year before, statistics show a huge gap between needs and the number of refugees that governments around the world are willing to accept.

More than ever, we must put in place effective relief and protection measures for displaced people.

The world needs political action.

Read more: A few countries take responsibility for most of the world’s refugees

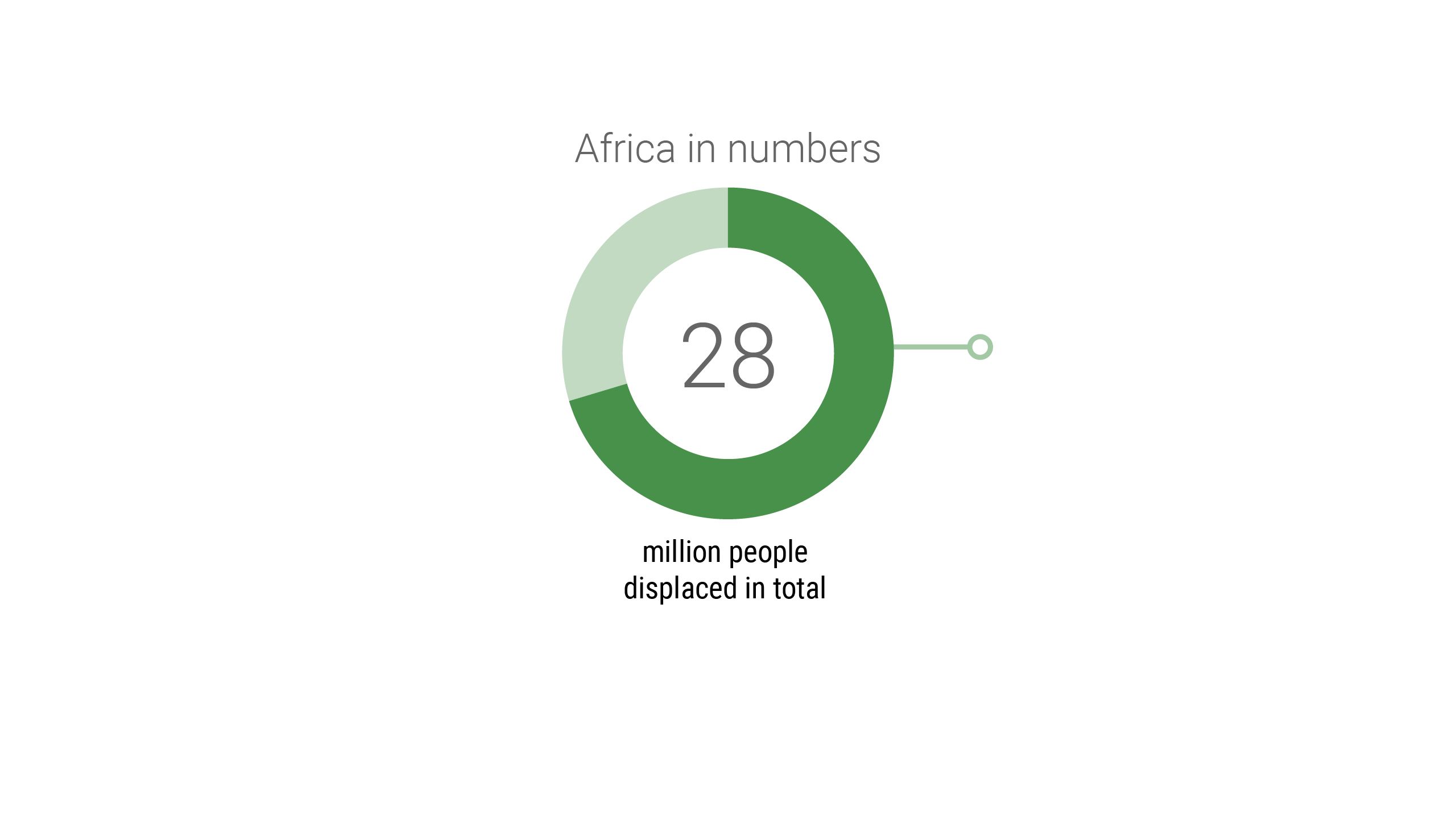

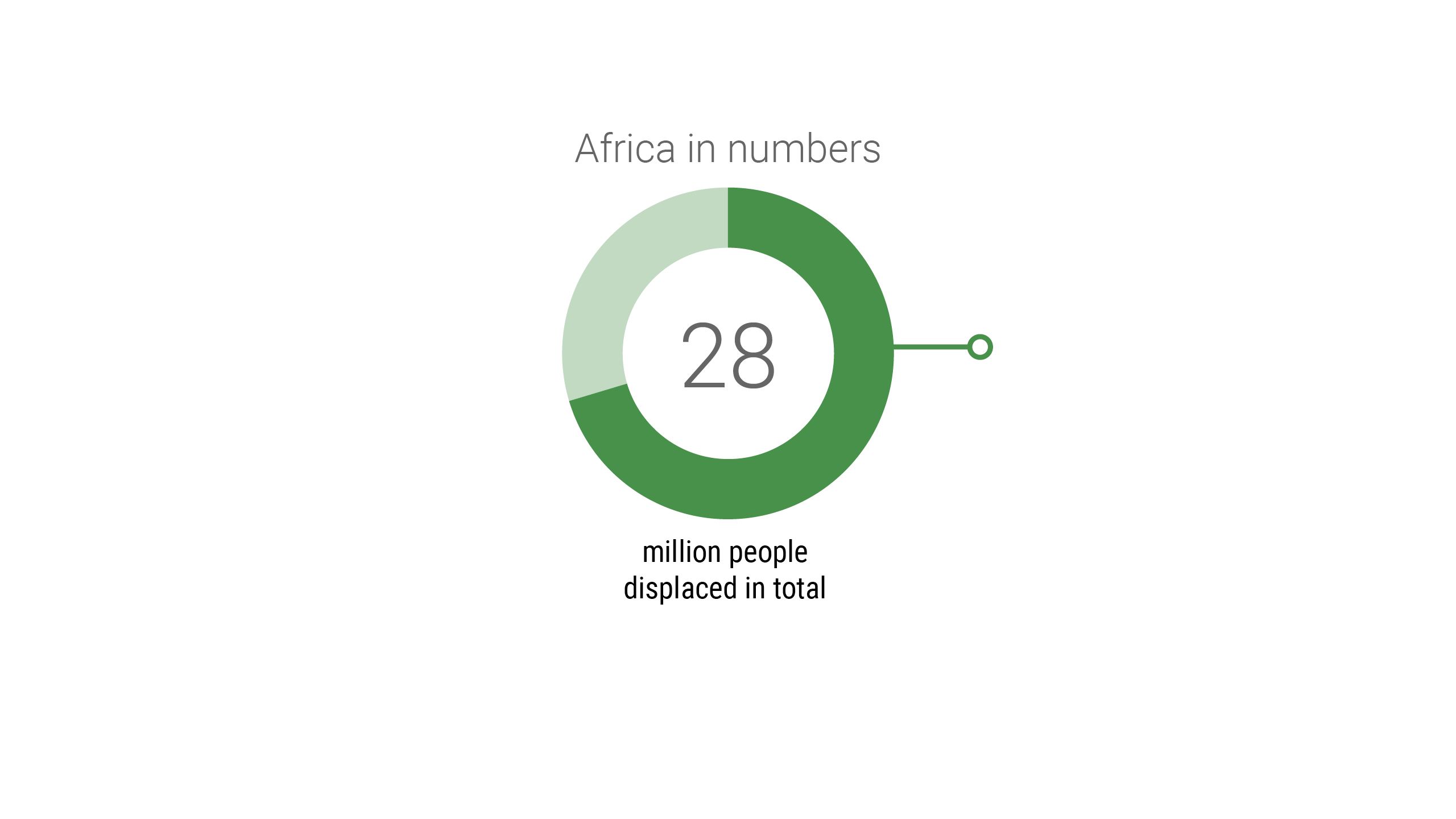

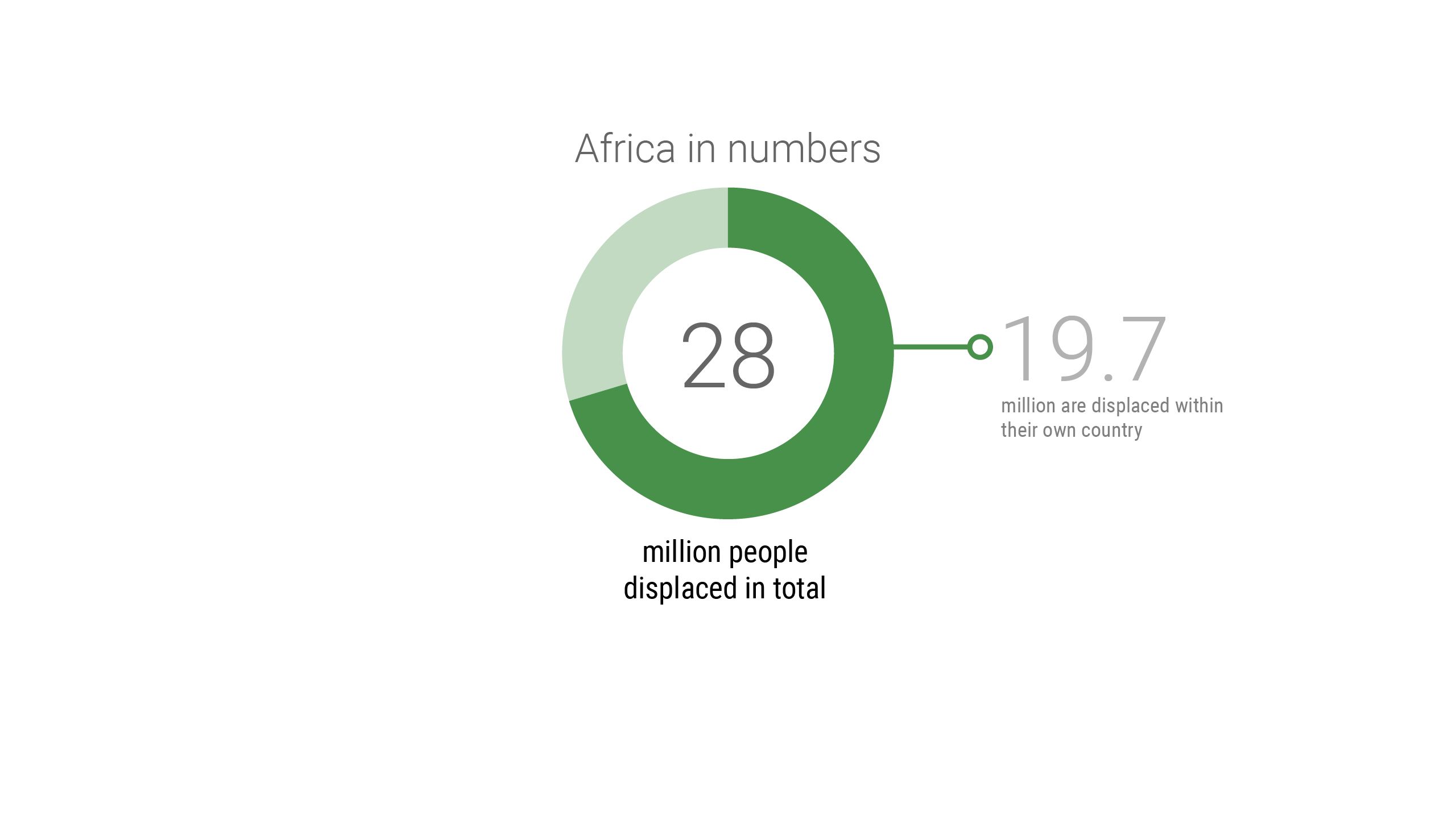

Africa

Nine out of the ten countries on NRC’s list of neglected displacement crises are in Africa. The list is based on three criteria: lack of political will, lack of media attention and lack of international aid.

Africa is Europe’s neighbour. What happens there is Europe’s concern as well. But many European politicians didn’t appear to realise that the Mediterranean is all that separates the two continents until a few short years ago, when the flow of migrants and refugees started to grow.

Displaced people in Africa deserve much more attention – and to have their basic human rights respected.

Not a good year for people in Africa’s conflict zones

The African continent is hugely complex in terms of language, ethnicity, nature, climate and economic development. The population of 1.3 billion is the youngest in the world and is growing the fastest of all the continents.

Only a limited number of African countries are seriously affected by violence and conflict. However, 2019 was not a good year for conflict-affected areas. The number of displaced people increased once again.

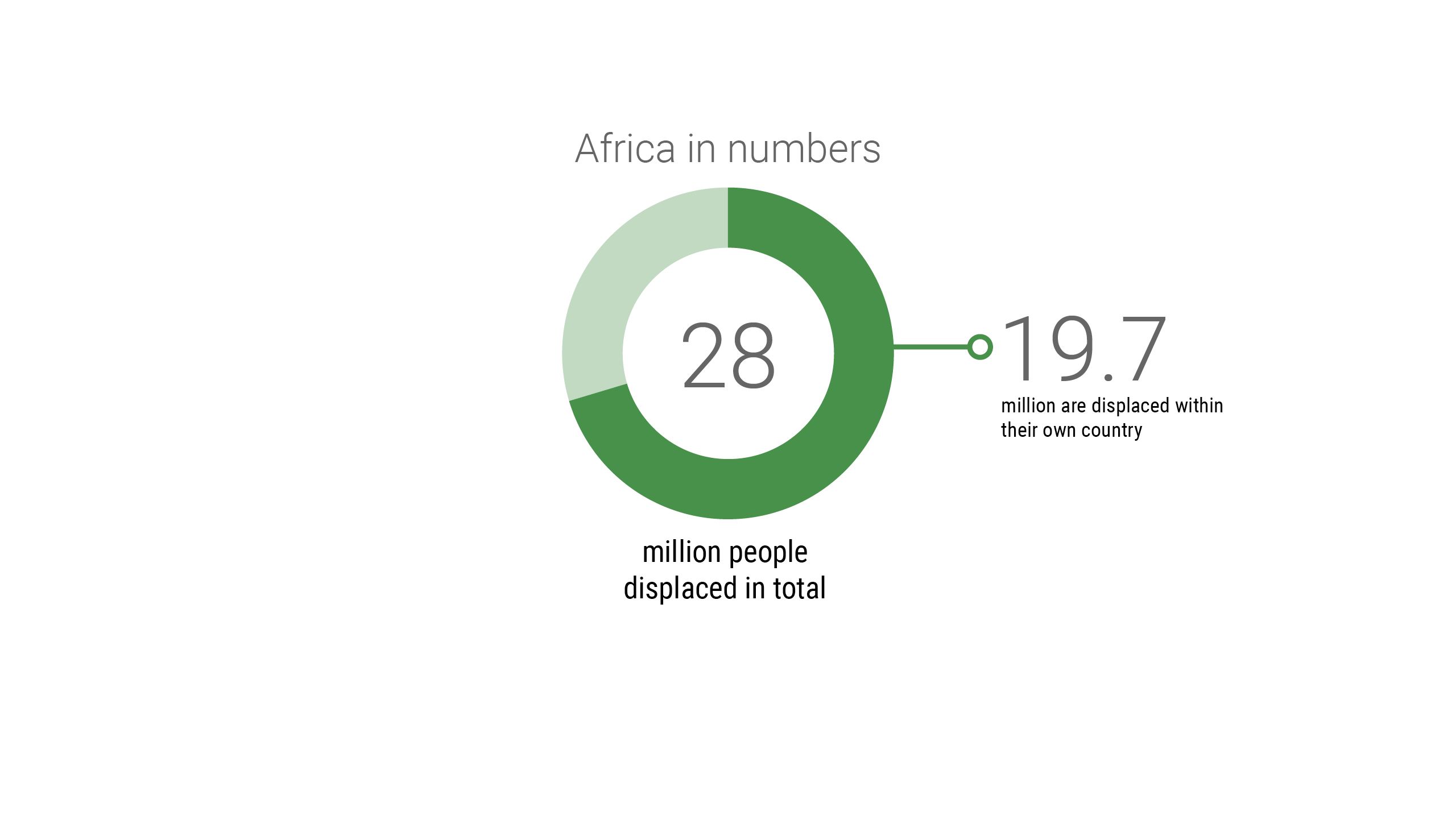

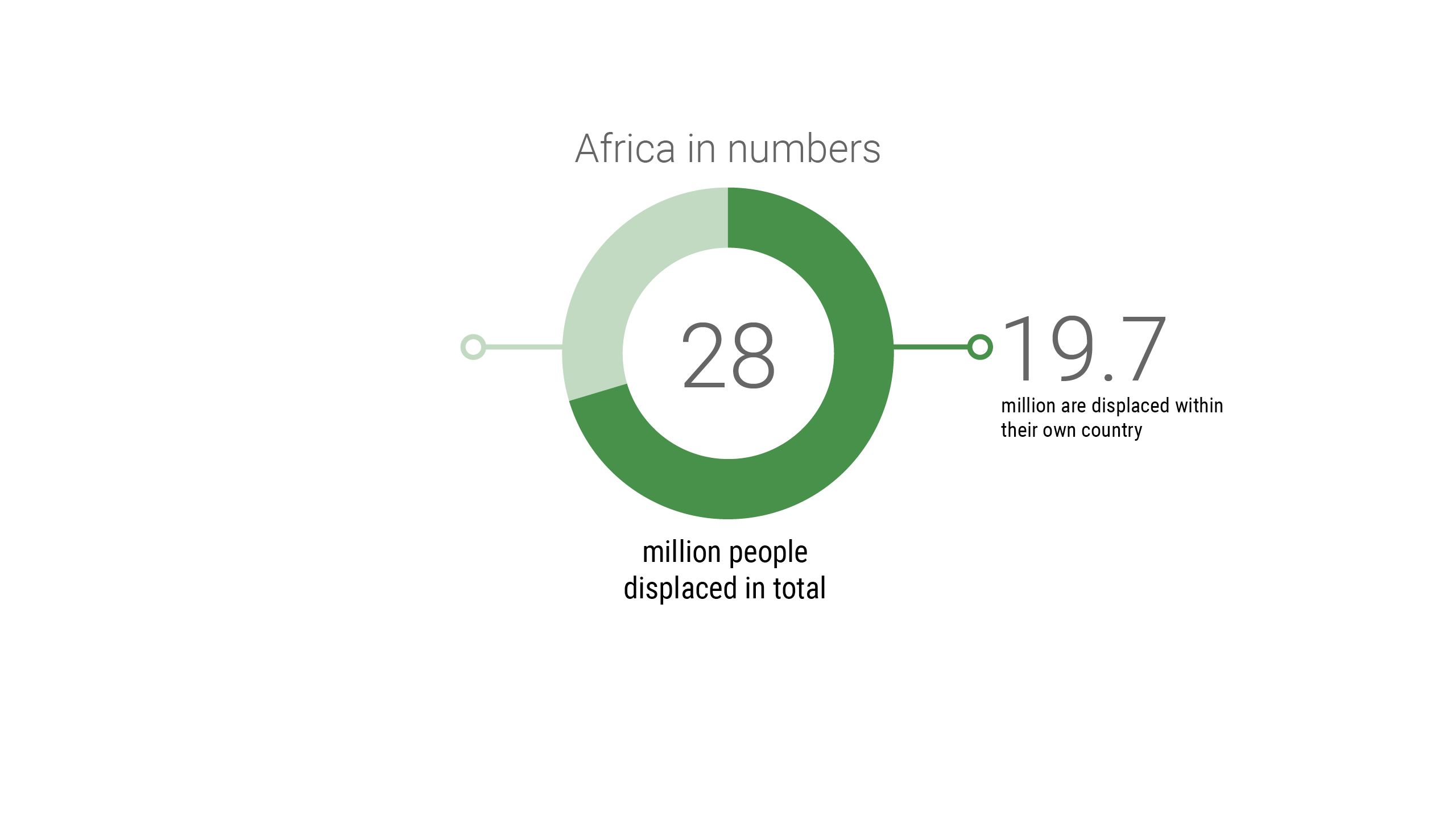

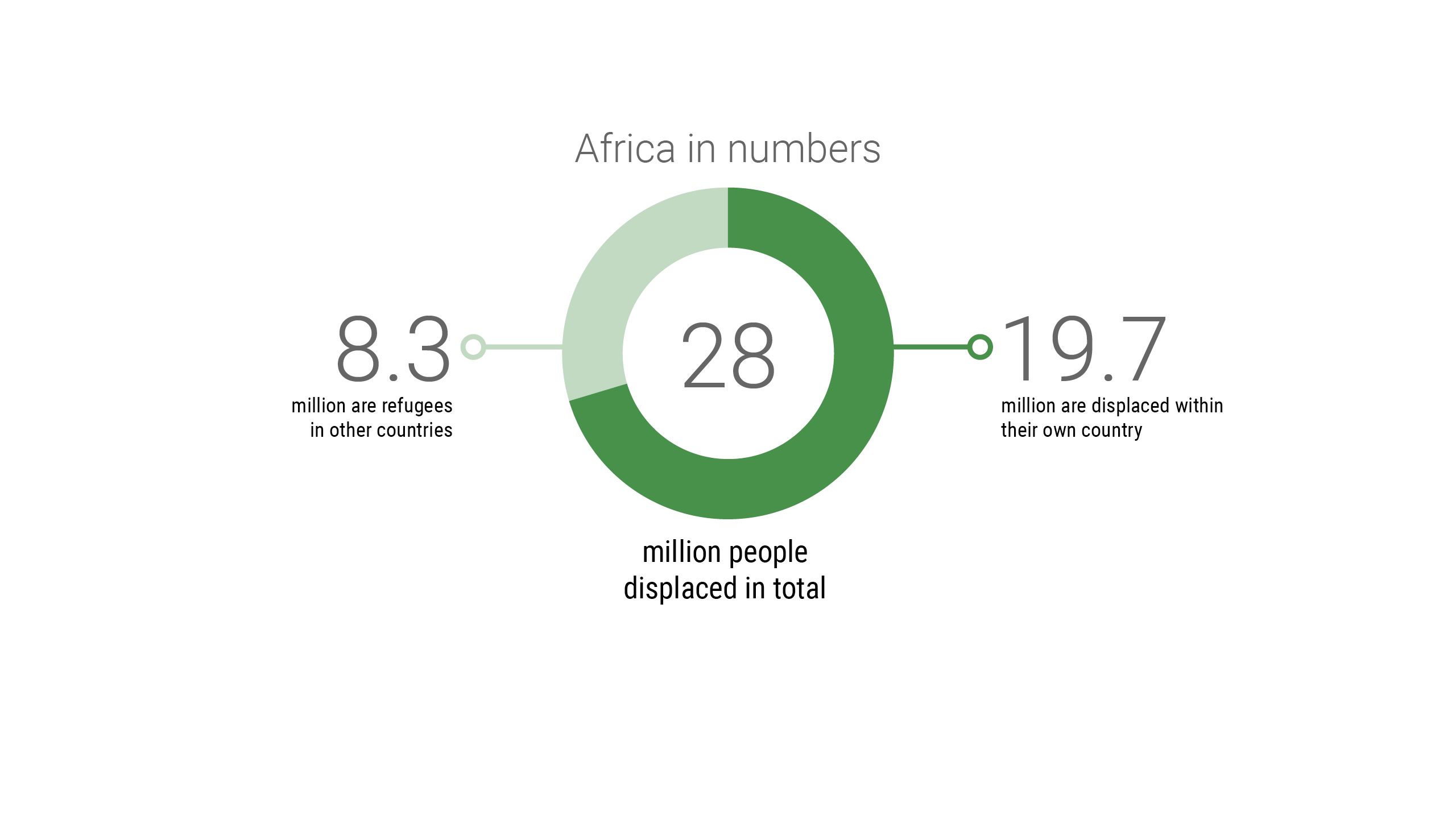

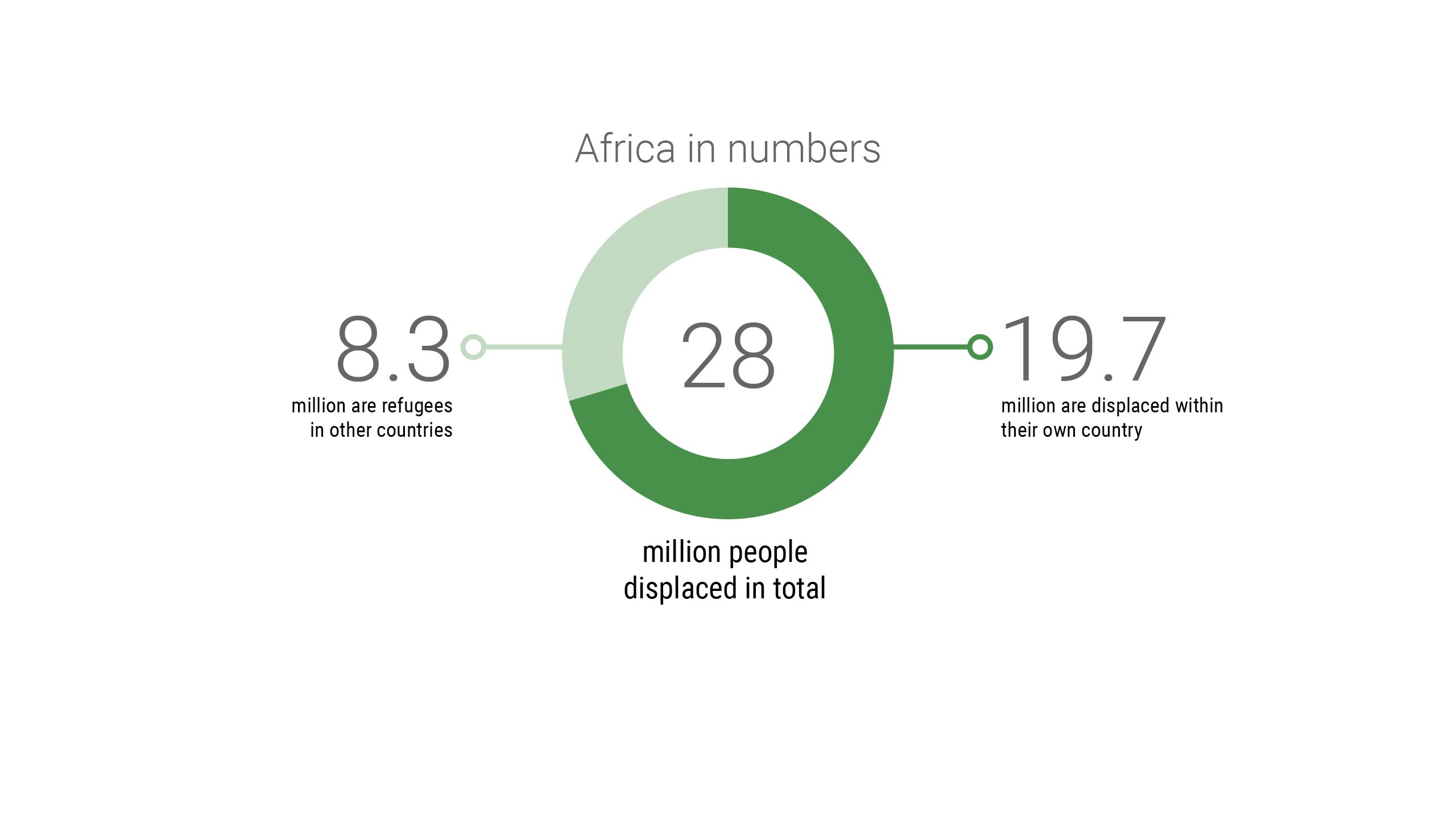

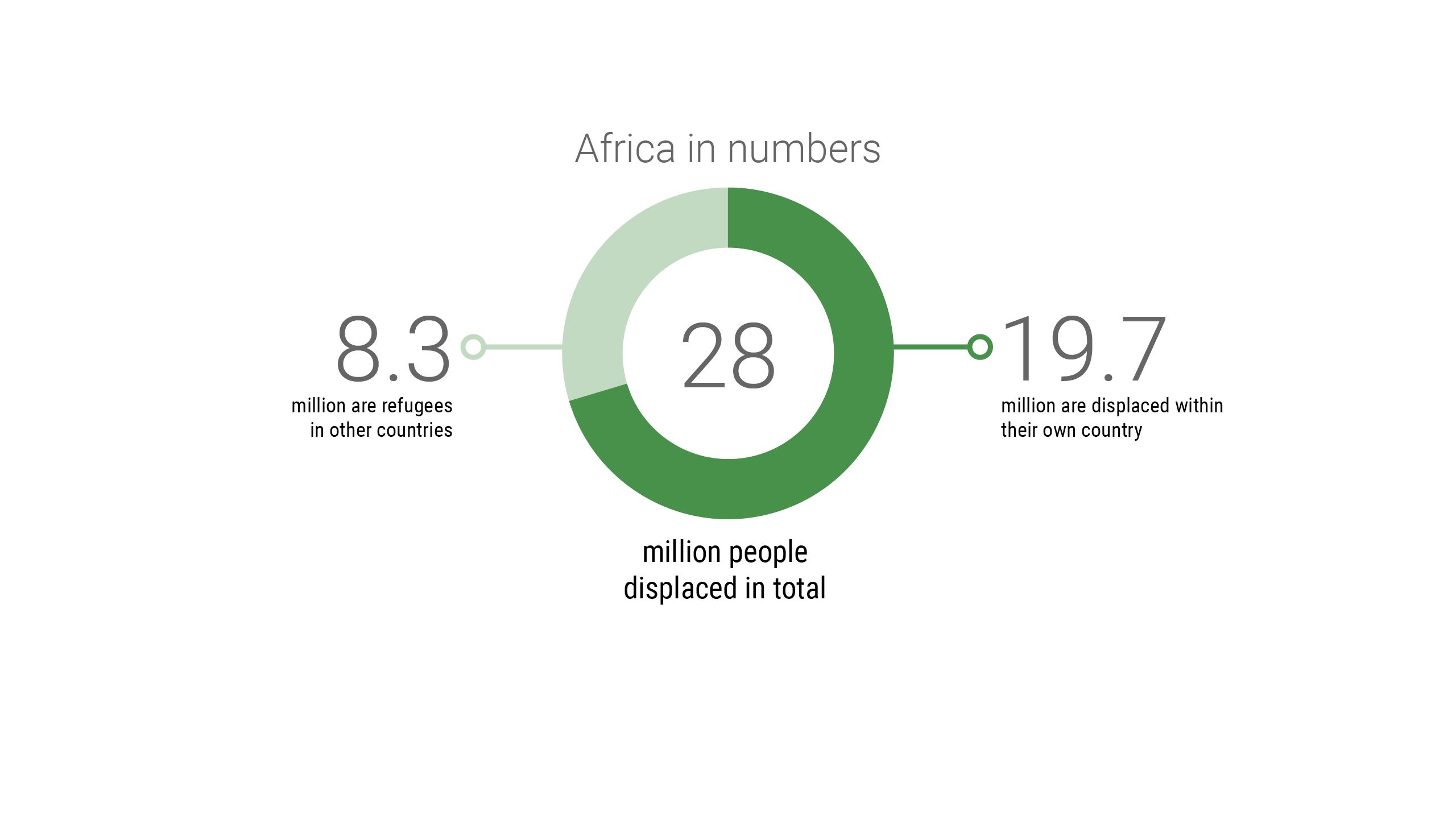

At the beginning of 2020, a total of 28 million people were displaced from their homes – 19.7 million were internally displaced, while the rest had sought protection beyond the borders of their homeland, usually in a neighbouring country.

It has proved very difficult to end protracted conflicts in countries such as DR Congo and Somalia. In addition, new conflicts have sprung up in the last decade, several of which are in danger of becoming long-term, such as those in Mali, Nigeria, Cameroon and Libya.

The climate crisis is hitting Africa hard

The climate crisis is global, but no continent has contributed less to it than Africa. Still, the people of Africa are among those feeling the most harmful effects. The average temperature has already risen so much that it has the potential to destroy the livelihoods of millions of people.

People are moving to the cities at a rapid pace in Africa, but the majority still live in rural areas where people are largely dependent on agriculture and livestock. This means that extreme weather such as drought and flooding will have major consequences for their daily lives and – most critically – access to food.

The countries that are afflicted by conflict are vulnerable, and government authorities are absent in some areas. When there is a crisis, people are often left to their own devices. This situation can be exploited by armed groups, which recruit young people who are disillusioned about the future. We see it especially in the world’s poorest region, the Sahel, which is located just south of the Sahara – and is therefore also highly vulnerable to climate change.

The climate crisis is increasing in scope. In recent years, both drought and floods have hit eastern and southern Africa with full force. Food production has been severely affected and the consequences are enormous in areas where there is ongoing armed conflict. This was the case in both Somalia and South Sudan in 2019.

Climate change also leads to other challenges. Higher temperatures are causing mosquitoes to spread malaria to new areas. The World Health Organization estimates that 350,000 Africans die from malaria every year.

Displaced Africans face myriad challenges

Climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic join the list of Africa’s many challenges. Extreme poverty, weak governance, large inequalities, poor health services and few educational opportunities present a challenging prospect for a young population.

Women queue for food at a camp on the outskirts of Mogadishu, Somalia in 2019. People in the camp have fled a prolonged drought which severely affected crops and livestock. Photo: Farah Abdi Warsameh/AP/NTB Scanpix

Women queue for food at a camp on the outskirts of Mogadishu, Somalia in 2019. People in the camp have fled a prolonged drought which severely affected crops and livestock. Photo: Farah Abdi Warsameh/AP/NTB Scanpix

Fanari Moustapha, 35, holds her one-month-old baby girl in her arms. The little girl isn't yet aware that she lives in a displacement camp in Cameroon, and that she and her three siblings will grow up without a father. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Fanari Moustapha, 35, holds her one-month-old baby girl in her arms. The little girl isn't yet aware that she lives in a displacement camp in Cameroon, and that she and her three siblings will grow up without a father. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

A young woman walks in one of the most congested displacement camps in Maiduguri, Nigeria. The Shuwari camp was one of the worst affected by the heavy flooding that hit Maiduguri in August 2019. Photo: NRC

A young woman walks in one of the most congested displacement camps in Maiduguri, Nigeria. The Shuwari camp was one of the worst affected by the heavy flooding that hit Maiduguri in August 2019. Photo: NRC

A displaced Libyan family visit their neighbours in an unfinished building in the Libyan capital, Tripoli. Around 470,000 Libyans are now displaced following the recent escalation of violence. Photo: Mahmud Turkia/AFP/NTB Scanpix

A displaced Libyan family visit their neighbours in an unfinished building in the Libyan capital, Tripoli. Around 470,000 Libyans are now displaced following the recent escalation of violence. Photo: Mahmud Turkia/AFP/NTB Scanpix

These children and their families fled an attack on their village and are now living in a displacement site in western Central African Republic (CAR). CAR is one of the world’s most neglected humanitarian crises. Photo: Hajer Naili/NRC

These children and their families fled an attack on their village and are now living in a displacement site in western Central African Republic (CAR). CAR is one of the world’s most neglected humanitarian crises. Photo: Hajer Naili/NRC

Families carrying their belongings flee the scene of an attack by an armed group in Halungupa village, north-east DR Congo. Photo: Alexis Huguet/AFP/NTB Scanpix February 2020

Families carrying their belongings flee the scene of an attack by an armed group in Halungupa village, north-east DR Congo. Photo: Alexis Huguet/AFP/NTB Scanpix February 2020

Ninety-year-old Dahabo lives in a displacement camp in north-east Somalia. She and her family used to be farmers but lost their livelihoods and animals to drought. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Ninety-year-old Dahabo lives in a displacement camp in north-east Somalia. She and her family used to be farmers but lost their livelihoods and animals to drought. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Farmers in South Sudan count the cost of a recent cattle raid. Competition for resources is one source of the conflicts in South Sudan. Photo: Tiril Skarstein/NRC

Farmers in South Sudan count the cost of a recent cattle raid. Competition for resources is one source of the conflicts in South Sudan. Photo: Tiril Skarstein/NRC

A local farmer tries to chase away a swarm of desert locusts outside Nairobi, Kenya. Large swarms of locusts threaten food production in many parts of East Africa. Photo: Dai Kurokawa/EPA/NTB Scanpix

A local farmer tries to chase away a swarm of desert locusts outside Nairobi, Kenya. Large swarms of locusts threaten food production in many parts of East Africa. Photo: Dai Kurokawa/EPA/NTB Scanpix

Key crises to watch in Africa

Escalating conflict drives new displacement in Libya

In Libya, 2019 saw an escalation of the country’s civil conflict. The Benghazi-based eastern government and the Libyan National Army (LNA) sought to capture Tripoli, the capital of the country and seat of the UN-recognised government. This has resulted in significant displacement, insecurity and disruptions to humanitarian aid.

An estimated 823,000 people are now in need of humanitarian assistance, with around 470,000 displaced in total following the recent escalation.

No peace in sight in the Sahel or DR Congo

In the areas of the Sahel and Central Africa most affected by conflict, the security situation deteriorated in 2019, forcing more people to flee.

This affected countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Cameroon, CAR, Nigeria and DR Congo, where the conflicts continued throughout 2019 and into 2020.

In DR Congo, 1.7 million people were displaced in 2019. In the period from March to May 2020, an additional 480,000 people were forced to leave their homes. The country has the second largest hunger crisis in the world after Yemen.

The conflicts in the north-west and south-west of Cameroon have displaced half a million people. There is no political solution in sight and fears persist that this could become a new protracted conflict on the African continent.

The number of displaced people in Burkina Faso increased tenfold in 2019, passing 560,000. The brutal violence in this country continued to force families to flee in spring 2020.

Both the security situation and the lack of funding for emergency aid make it difficult to meet the needs of displaced people in Burkina Faso. In 2019, donor countries contributed less than half of the funds needed.

Violence increases as Lake Chad slowly dries up

On the border between Chad, Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon lies Lake Chad. It provides water to over 20 million people.

But due to over-consumption and rising temperatures, the lake is slowly drying up.

Around Lake Chad, violence is raging with full force after more than ten years of armed conflict. Niger, Chad and northern Cameroon have all been drawn into the spiral of violence, which has north-east Nigeria – where Boko Haram started its uprising in 2009 – as its epicentre.

The civilian population is extremely vulnerable to attacks by armed groups and to counter-offensives by the military. Many people flee to isolated areas that are very hard to reach with aid.

The military efforts to stifle violence in the Sahel have failed to improve the security situation. Instead, the situation has worsened.

Providing protection for millions with little support

In East Africa, there are large variations between different regions. Somalia and South Sudan are among the countries in the world with the largest number of displaced people. Meanwhile, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania have all welcomed millions of refugees.

International support for countries that have taken in refugees in East Africa has been entirely inadequate considering the number of people for whom these countries provide protection.

Excluding the countries that welcomed Venezuelans, no country in the world received more refugees than Uganda in 2019. Almost 1.4 million refugees now reside there, an increase of 190,000 during 2019. This is mainly due to an influx of people from South Sudan and DR Congo, while thousands more came from Somalia and Burundi.

Despite this, UNHCR and their partners received only 40 per cent of the funds necessary to meet the humanitarian needs in 2019.

Swarms of locusts blocked out the sun

East African countries faced a common challenge in the first months of 2020. Swarms of several billion locusts ate up everything they came across, threatening food security in already vulnerable areas. The situation was particularly bad in Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya.

This crisis happened at the same time as the Covid-19 pandemic hit and there is good reason to fear the consequences – especially in relation to people's access to food.

Ethiopia in focus

The 2019 Nobel Peace Prize went to Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed for his contribution to making peace with Eritrea and to reconciliation processes in neighbouring countries, and for his will to strengthen democracy in his home country.

However, Ethiopia has also been experiencing internal tensions and conflicts, at the same time as being an important host country for refugees fleeing conflict, repression and poverty in neighbouring countries. When Ahmed’s government undertook important reforms, it raised hopes of positive development for the whole of the Horn of Africa. But now Ethiopia’s political experiment appears more uncertain.

New conflict brewing in Mozambique

At the end of April 2020, rebel groups joined forces with IS group to take temporary control of two cities in northern Mozambique. There has been a gradual deterioration of the security situation in the area and thousands of people have been displaced.

There is reason to fear a further escalation of hostilities in the times to come.

Middle East

and Asia

A mother tries to entertain her daughter while waiting at the reception centre in Kala Meera village, Iraq, close to the border to Syria. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

A mother tries to entertain her daughter while waiting at the reception centre in Kala Meera village, Iraq, close to the border to Syria. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

A young boy stands in front of the damaged building he calls home. Around 650 families live in this informal settlement in Anbar, Iraq, where water and electricity are in short supply. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

A young boy stands in front of the damaged building he calls home. Around 650 families live in this informal settlement in Anbar, Iraq, where water and electricity are in short supply. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

Palestinians collect their belongings after Israeli forces demolished their house in the West Bank city of Yatta, south of Hebron, in June 2020. Photo: Abed Al Hashlamoun/EPA/NTB Scanpix

Palestinians collect their belongings after Israeli forces demolished their house in the West Bank city of Yatta, south of Hebron, in June 2020. Photo: Abed Al Hashlamoun/EPA/NTB Scanpix

A displaced man in a camp in northern Yemen. The camp hosts more than 1,000 people who were forced to flee their homes by escalating fighting in 2019. Photo: Yahya Arhab/EPA/NTB Scanpix

A displaced man in a camp in northern Yemen. The camp hosts more than 1,000 people who were forced to flee their homes by escalating fighting in 2019. Photo: Yahya Arhab/EPA/NTB Scanpix

Mohammad Jamal, 45, and his family rely on neighbours and nearby shops to access free water. Life is hard in this drought-stricken area of Herat province, Afghanistan. Photo: Enayatullah Azad/NRC

Mohammad Jamal, 45, and his family rely on neighbours and nearby shops to access free water. Life is hard in this drought-stricken area of Herat province, Afghanistan. Photo: Enayatullah Azad/NRC

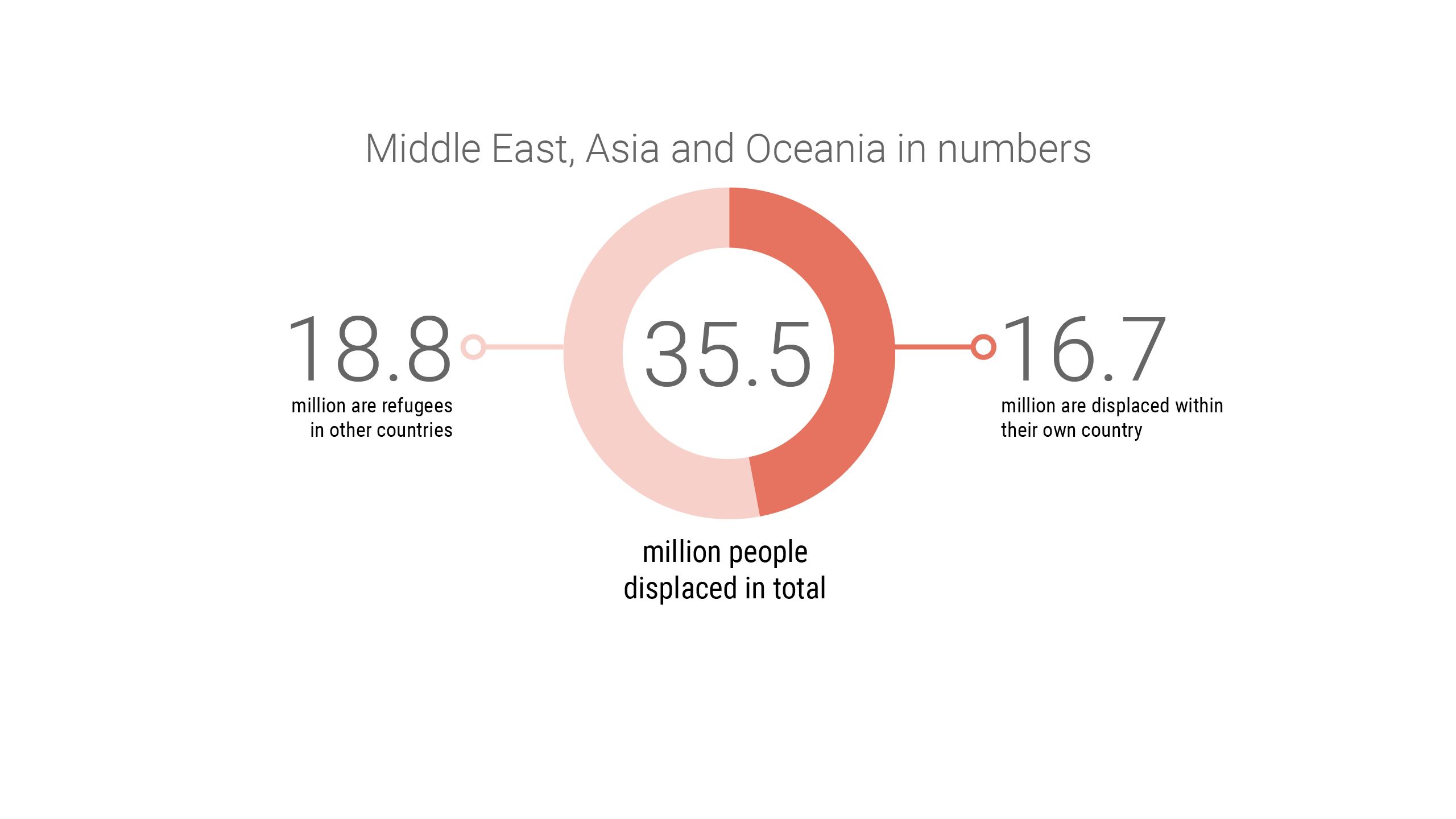

The security situation across the Middle East region is volatile, with periodic escalations of violence leading to mass displacement.

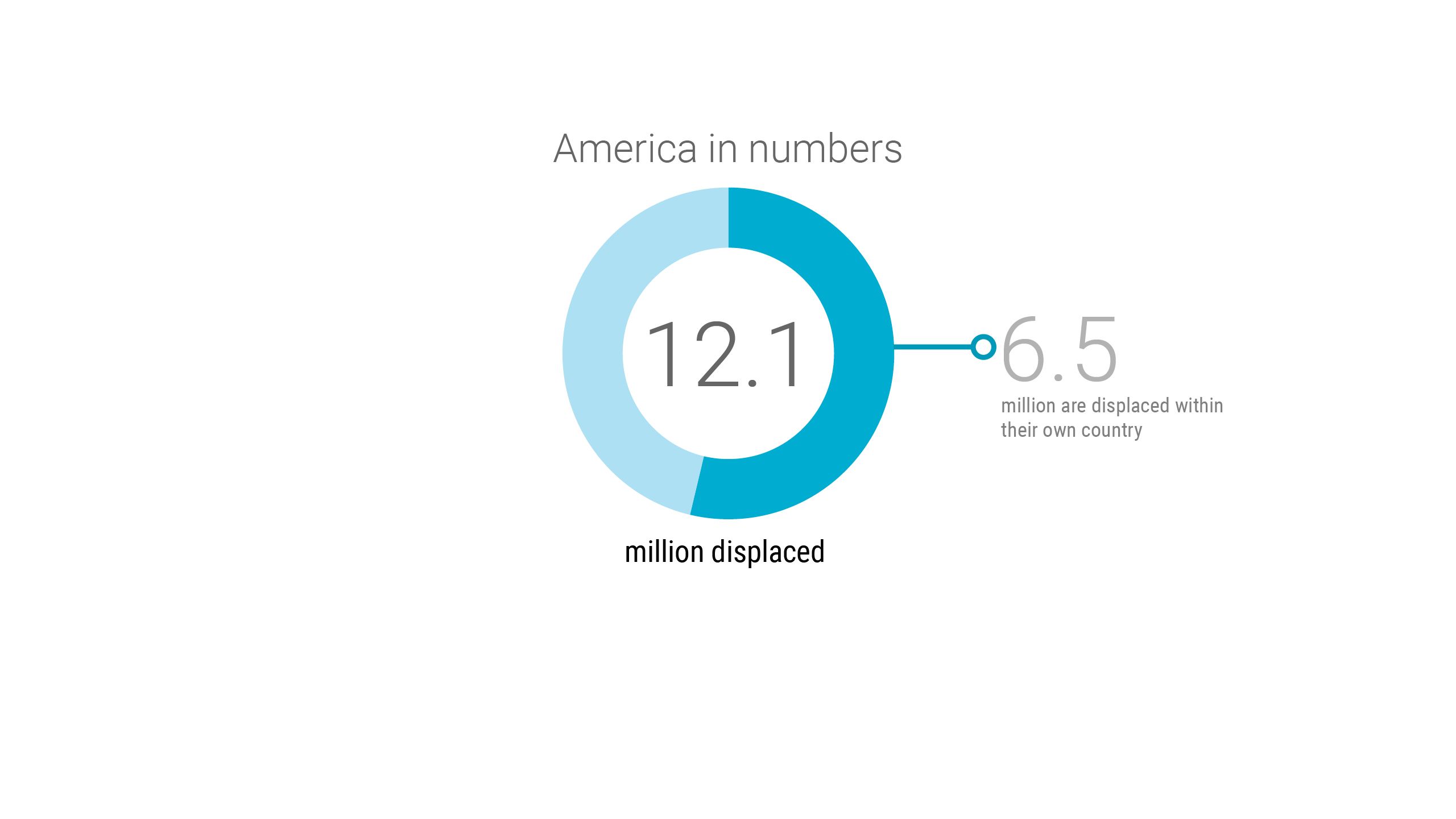

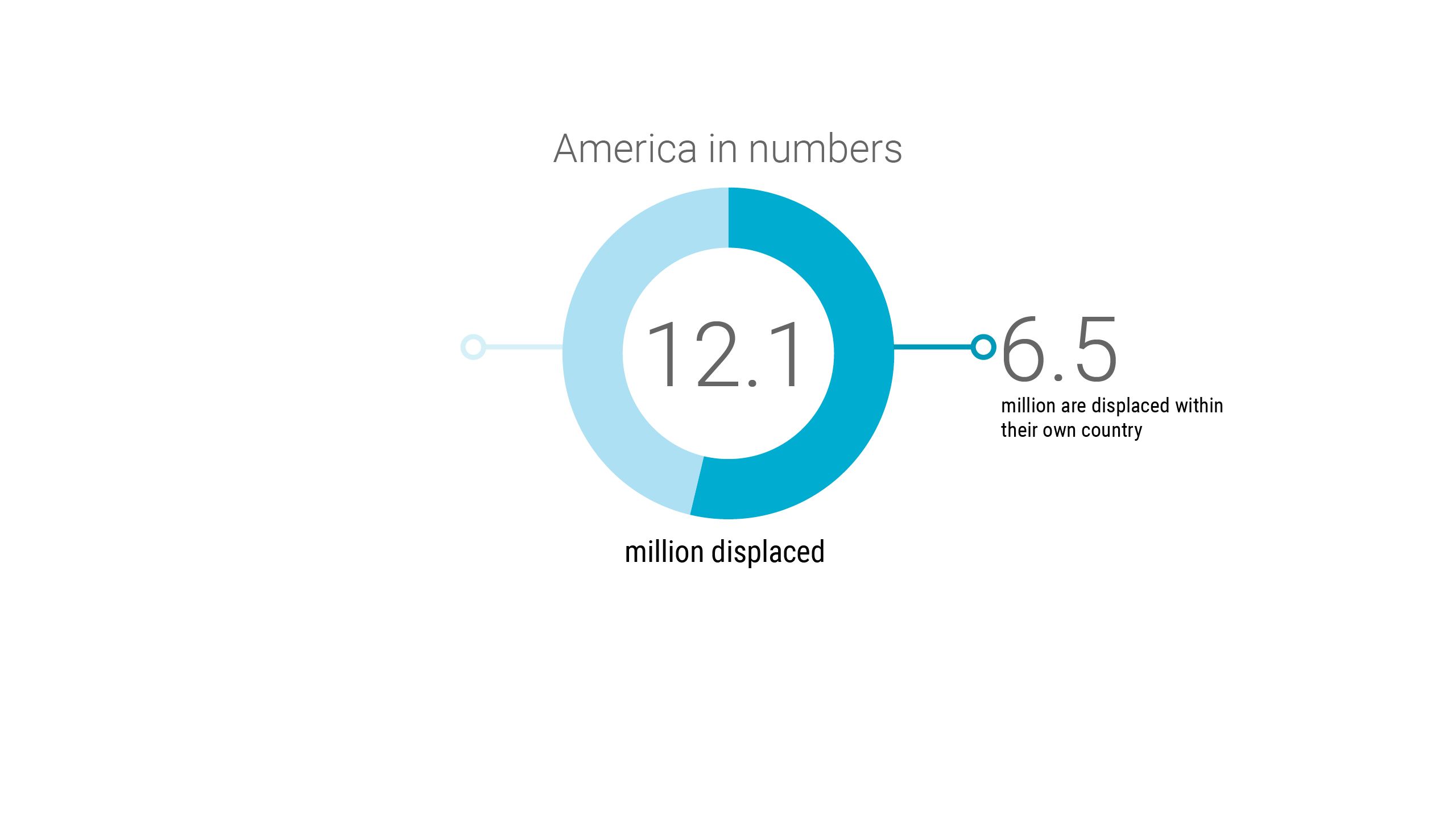

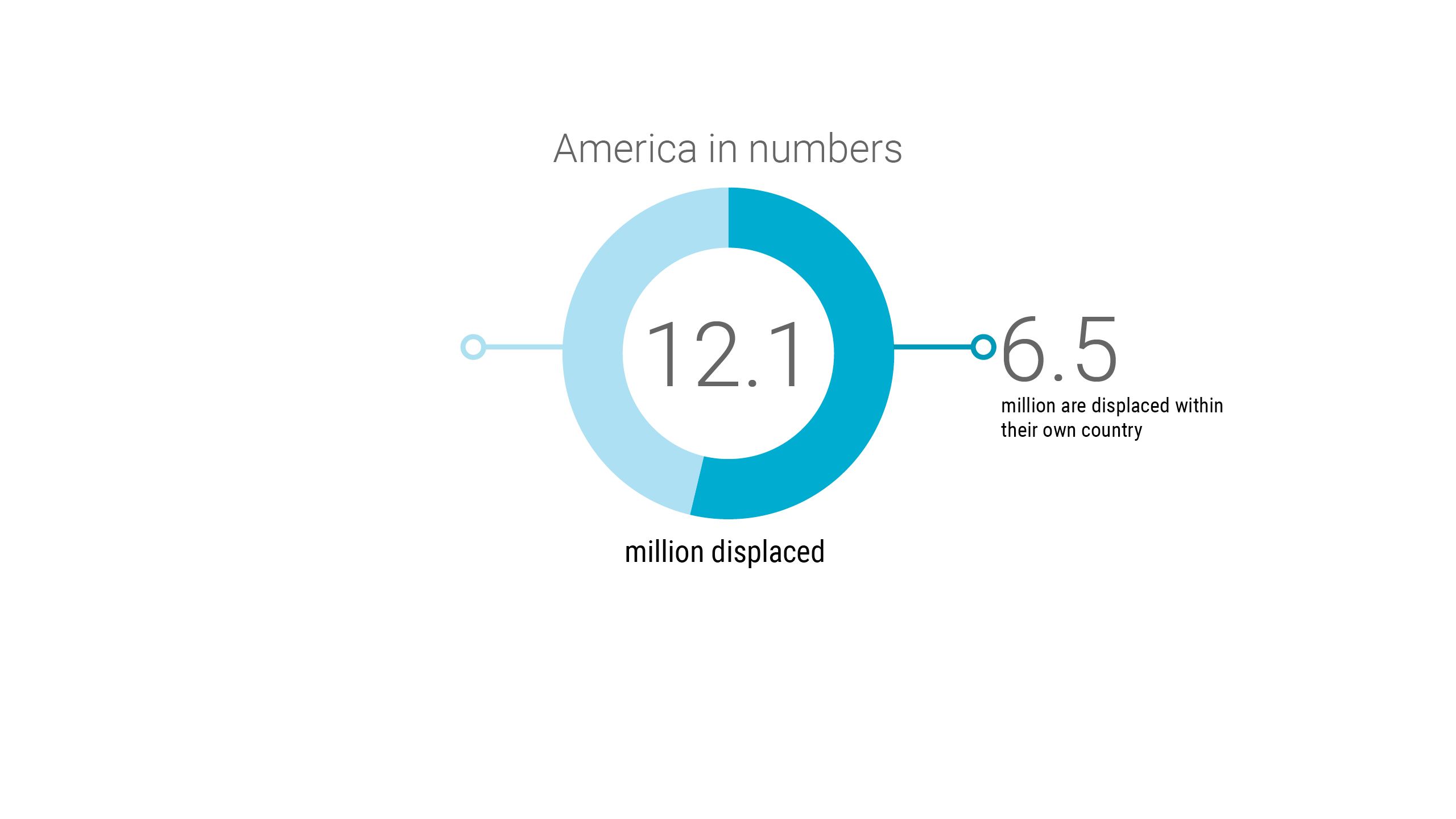

Syria remains largest displacement crisis

Syria remains the epicentre of a massive humanitarian crisis, with nearly 12 million people in need of assistance and half the pre-war population forced to flee their homes.

A total of 6.5 million are displaced within Syria itself and 6.7 million more have fled across the country’s borders as refugees.

Syria has experienced significant shifts in territorial control over the last few years, with the Government of Syria regaining much of the territory in the south and centre of the country.

In late 2019 and early 2020, an escalation of conflict in the north-west of the country caused over 900,000 people to flee to their homes, many living in dire conditions. In north-east Syria in 2019, a Turkish military operation displaced more than 220,000 people. In government-held areas, massive needs remain.

Lebanon and Jordan host more than 1.5 million syrian refugees

Lebanon continues to host approximately 900,000 Syrian refugees and 500,000 Palestinian refugees. This is one of the largest concentrations of refugees per capita in the world.

From mid-October 2019, protests broke out across the country, triggered by the deterioration of an economy that has been slowly collapsing over several years. The economic collapse, coupled with Covid-19 measures, risks disproportionately hitting the huge refugee population in the country.

Over 650,000 refugees from Syria are also registered in Jordan, with 83 per cent living in urban areas across the country and the rest in refugee camps.

Recent surveys of refugees from Syria show that there is still a strong wish to return to their home country at some point. However, Syrians will not return until they trust that they will be safe, and able to reclaim their property, sustain their families and access basic services.

For most displaced Syrians, this is a distant prospect.

Iraq: devastation, discrimination and continued displacement

Iraq remains a country in crisis, even though it has been three years since the defeat of the Islamic State group was declared. Approximately 1.6 million people remain displaced within its borders. The devastation of cities and towns, as well as discrimination against displaced people, particularly women, present major barriers to return, rehabilitation and reconstruction.

Iraq also hosts almost 250,000 Syrian refugees, including recent arrivals fleeing the Turkish military operation in northern Syria.

2019 witnessed a growing economic and political crisis as well as an increase in attacks by Islamic State group.

The multiple crises facing Iraq have been compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic. The impact of lockdown measures and the collapse in the international price of oil have led to an unprecedented economic decline.

Moves to annex of West Bank further erode Palestinian rights

All of the roughly five million Palestinians in the occupied territory still live in uncertainty, and half of them need humanitarian assistance.

With the tacit encouragement of the United States, the new Israeli government formed in April 2020 wants to annex large parts of the West Bank. The plan proposes that the Jordan Valley, comprising roughly one-third of the West Bank, would come under Israeli sovereignty. Much of the Palestinian population in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip will remain in the enclaves under the nominal control of the Palestinian Authority or Hamas.

In the midst of this, and despite the Covid-19 pandemic, demolitions, evictions and threats of forcible transfer are ongoing. Since the arrival of Covid-19 in Israel and Palestine, 69 structures in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, have been demolished, forcibly displacing 63 people.

Yemen labelled “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis”

After more than five years of war and a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, the future looks bleak in Yemen. The scale and severity of the crisis mean has led the UN to call it the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

The situation in the war-affected country has been further aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Failure in international aid could trigger famine and outbreaks of cholera and coronavirus infection, among other diseases.

In the spring of 2020, more than 5.5 million people were at risk of losing access to food, water and medicine.

Around 24 million people need help and protection. This is 80 per cent of the entire population.

Conflict, drought and political instability in Afghanistan

After 40 years of war and conflict, nine million Afghans still need humanitarian aid. A total of three million people have fled the country, most of them to neighbouring Iran and Pakistan.

Almost three million people have been internally displaced by conflict. Of these, 461,000 were forced to flee in 2019 alone. In addition, hundreds of thousands have fled due to drought.

Many who have been internally displaced for a long time are living in slum-like settlements in or around the capital Kabul. These are overpopulated areas where people are highly vulnerable to the spread of Covid-19. Residents lack access to clean water and the sanitary conditions are miserable.

Drought in the western parts of Afghanistan, combined with the poor security situation, political instability, high levels of malnutrition among children under the age of five and rising poverty, make everyday life extremely difficult for many Afghans.

Around 9 out of 10 Afghans live below the UN’s threshold for extreme poverty.

Around 9 out of 10 Afghans live below the UN’s threshold for extreme poverty.

Despite the difficult situation in Afghanistan, some displaced Afghans are returning home. In the spring of 2020, many withdrew from Iran in fear of Covid-19. There is no system for testing the people returning home and the humanitarian response has been focused on hygiene measures and providing information.

One political bright spot is that on 20 May, the Taliban stated that they still support the agreement with the United States. According to that agreement, the United States will completely withdraw from Afghanistan by 2021.

The Rohingya are stuck in limbo

They are stateless. They have been displaced. They have been neglected for decades. And that’s why the UN has referred to the Rohingya population, from the state of Rakhine in Myanmar, as one of the world’s most persecuted peoples.

In recent years, the situation has gone from bad to worse. A military counter-offensive in Rakhine in August 2017 forced over 700,000 Rohingya to flee across the border to neighbouring Bangladesh, where they have since remained in a state of limbo.

Denied formal refugee status by the government of Bangladesh, they are in practice unable to return to Myanmar, where they fear violence and persecution. In addition, the Rohingya refugees are vulnerable to cynical human traffickers.

In total, there are around 900,000 Rohingya refugees spread across 34 camps in Bangladesh. The help they receive with protection, health and hygiene, education and shelter is very limited.

The cramped living conditions and their already poor state of health make the refugees especially vulnerable to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Long-running conflicts in Myanmar

The conflict between the authorities and various ethnic minorities has deep roots in Myanmar. The country has been the scene of armed conflicts ever since its independence from the British in 1948. While there are ceasefire agreements with some of the groups, the violence continues elsewhere.

The UN estimates that 950,000 people are in need of humanitarian assistance in Myanmar. Of these, 240,000 have been displaced in conflict zones located in the border areas of China, Bangladesh and Thailand.

In Thailand, there are still 97,000 refugees from Myanmar in nine camps. Most of them have been there for decades.

This refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, is built on sandy hills - challenging terrain for housing thousands of refugees. Landslides happen frequently during the monsoon season. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

This refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, is built on sandy hills - challenging terrain for housing thousands of refugees. Landslides happen frequently during the monsoon season. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

America

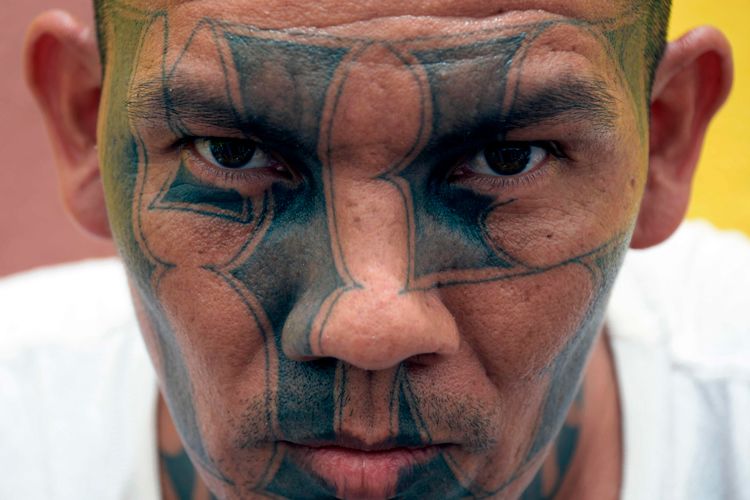

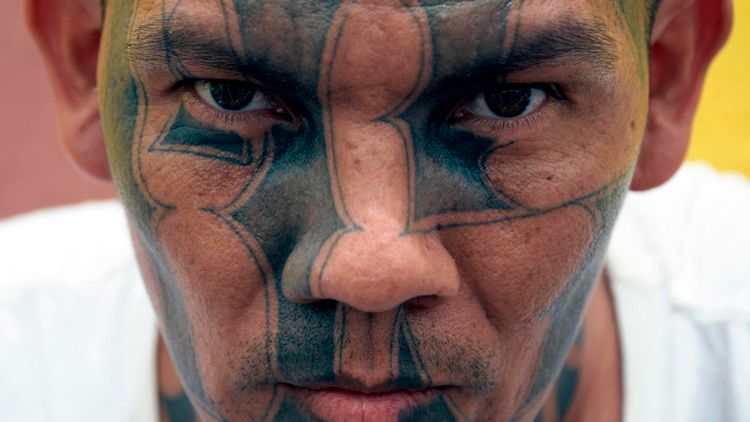

A member of the MS-13 gang in Chalatenango prison, El Salvador. This criminal gang originated in Los Angeles in the 1970s, and was originally set up to protect Salvadoran immigrants. Photo: Marvin Recinos/AFP/NTB Scanpix

A member of the MS-13 gang in Chalatenango prison, El Salvador. This criminal gang originated in Los Angeles in the 1970s, and was originally set up to protect Salvadoran immigrants. Photo: Marvin Recinos/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Many vendors have had to close their stalls in this Venezuelan market due to the economic crisis. There used to be 167 vendors here, but by mid-2019 fewer than half remained. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Many vendors have had to close their stalls in this Venezuelan market due to the economic crisis. There used to be 167 vendors here, but by mid-2019 fewer than half remained. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Demonstrators in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, demand the resignation of Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez in October 2019 for his alleged links to drug trafficking. Photo: Orlando Sierra/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Demonstrators in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, demand the resignation of Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez in October 2019 for his alleged links to drug trafficking. Photo: Orlando Sierra/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Honduran migrants set out for the Guatemalan border in April 2019. Almost 1,000 people gathered in a caravan bound for the United States in search of work or to escape drug-traffickers. Photo: Orlando Sierra/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Honduran migrants set out for the Guatemalan border in April 2019. Almost 1,000 people gathered in a caravan bound for the United States in search of work or to escape drug-traffickers. Photo: Orlando Sierra/AFP/NTB Scanpix

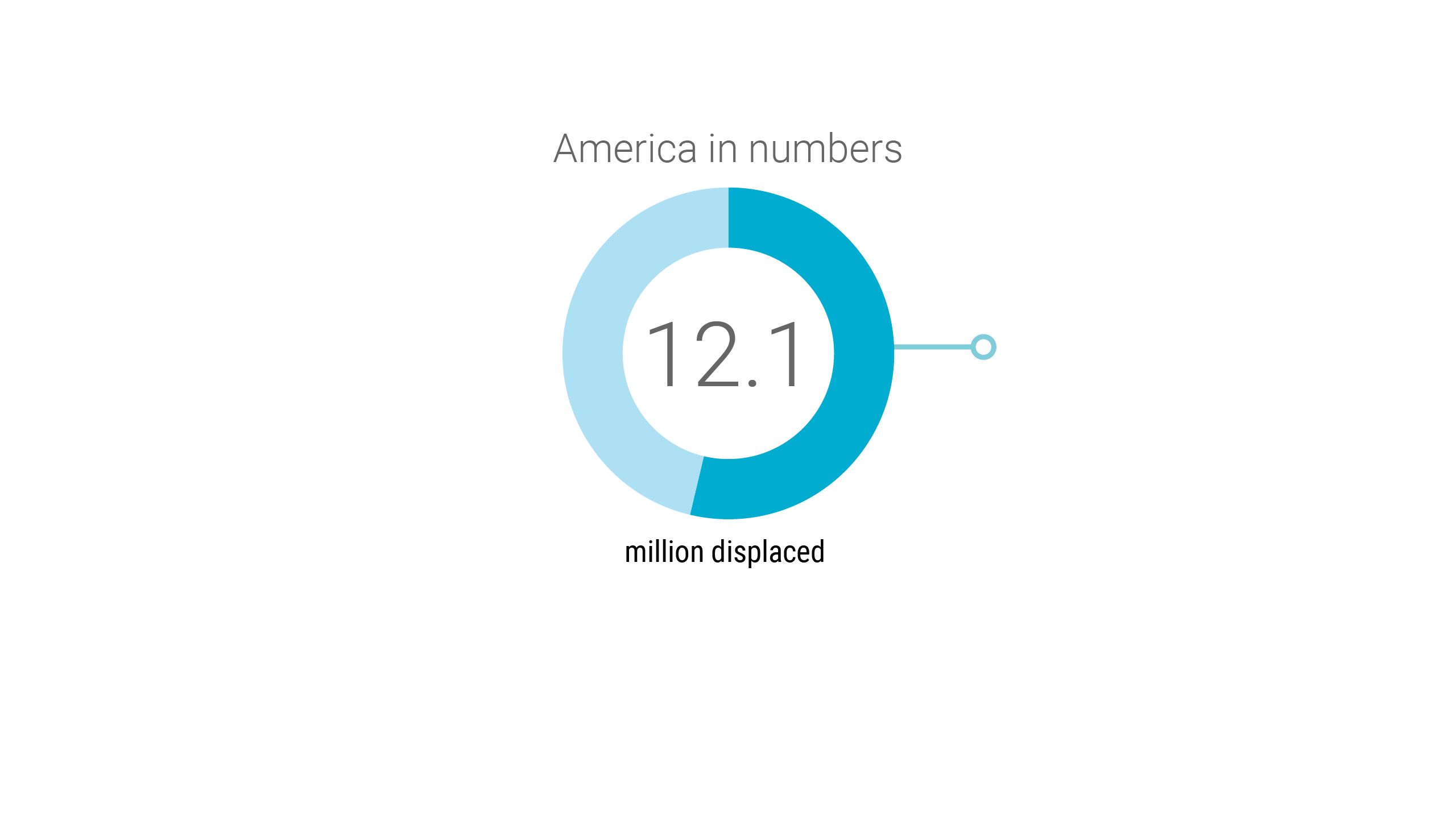

Three humanitarian crises stand out in Latin America:

The extreme violence in Central America comes mainly from organised criminal gangs. This deadly phenomenon affects whole communities, and particularly children and young people.

The loss of human life and the number of displaced people is on a par with what we find in war zones elsewhere in the world.

In Venezuela, the population is struggling with inflation, deep poverty, increased crime, and food and medicine shortages. By the spring of 2020, more than five million people had left the country.

Colombia is still a divided country with great contradictions. Despite the peace agreement between the government and the former FARC armed group in 2016, armed conflict continues in many rural areas.

Protests looming

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, Latin America had experienced seven years of weak economic development. In the autumn of 2019, this sparked social protests in several countries, such as Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, Nicaragua and Honduras. There is a strong risk of more turmoil and polarisation in the months ahead.

In several Latin American countries, large sections of the population work in the informal sector or in the black market economy, without any kind of safety net. The consequences of Covid-19 could be drastic in those countries and regions that are already experiencing a humanitarian crisis – Central America, Venezuela and Colombia.

Violence affects the daily lives of millions across Central America

The combination of drugs, gangs, poverty and criminal impunity has led to extreme violence in Central America.

The spiral of violence hinders economic development and growth in the region. Countries are missing out on investments, and violence is causing fear and trauma among the population. Criminal gangs are also involved in human trafficking, and children are used as drug mules or to carry weapons.

Organised crime displaces and kills

Violence is often the trigger for the flood of refugees and migrants heading north toward the US border. People have been living with poverty, corruption, criminal impunity and weak state institutions for decades. Nevertheless, threats and violence cause many people to leave their homes and families.

Although the murder rate has fallen in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala since 2016, violence is still widespread. During 2019 alone, 454,000 people were displaced from their homes within El Salvador.

Young people are vulnerable

The violence perpetrated by criminal networks hits young people especially hard. Young people flee because of family members being murdered, forced recruitment to gangs, sexual violence, fear of kidnapping and general insecurity.

In the past eight years, almost 9,000 children have been reported missing in Guatemala alone. Globally, there are almost 470,000 refugees and asylum seekers from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. The number has increased by 33 per cent since 2018.

Displaced in the time of Trump and Covid-19

Government measures to stop the pandemic have limited the opportunities to reach people with humanitarian aid. It has become more difficult for displaced people to get into neighbouring countries because the borders are closed.

Many people persist in trying to flee from El Salvador and Honduras, but North American authorities are now arresting migrants and people in need of international protection and sending them to the Guatemala–Mexico border. Many who have spent time in detention centres near the US border have also been sent back by Mexican police.

President Donald Trump made a new deal with Mexico in 2019, claiming that illegal immigration was a threat to US security. Since the new rules were introduced, more than 62,000 migrants and asylum seekers who had managed to cross the border have been sent back to border towns on the Mexican side.

While their asylum applications are being processed, thousands are forced to wait in Mexican territory, where they live in great insecurity and with minimal support in areas where the Mexican drug cartels have a lot of power and influence.

Colombia – a polarised society

The peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC armed group was seen as a huge success. However, the implementation of the agreement has been problematic. The contrasts in Colombia are still strong, as reflected in nationwide demonstrations against corruption, the killing of social leaders and extreme inequality in the autumn of 2019. The country has welcomed around 1.8 million Venezuelans.

Due to the continued lack of government presence in many rural places, large areas previously controlled by FARC are now occupied by criminal gangs, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and guerrilla and paramilitary groups.

Nor has the government been able to provide protection for its own citizens. A total of 750 social leaders and nearly 200 demobilised FARC soldiers have been killed since the peace agreement was signed. Although the paramilitary groups were dissolved on paper in 2005, it is obvious that they still exist and are operational.

The 2016 peace agreement promised improvements for people in rural areas, but very little has happened. This also helps explain why many farmers continue be forced and threatened into growing coca, which strengthens the criminal organisations and other armed groups.

Most of those displaced in Colombia come from rural areas. Ongoing insecurity and violence mean that many cannot return.

Venezuela – the biggest migration and displacement crisis in Latin America

In 2015, 700,000 Venezuelans had left their homeland. By April 2020, that figure had reached five million. Lack of food, medicines, increased crime, political violence and sanctions have made life unbearable. A stream of Venezuelans has been travelling to neighbouring countries.

The arrival of Venezuelans in Latin American countries is overwhelming the local capacity to respond. Additionally, Venezuelans are now subjected to various types of harassment. There are also reports of them being recruited to criminal gangs and armed groups. Women and children are subject to sexual exploitation and many are forced to resort to prostitution in order to survive.

Humanitarian aid work has been limited and Venezuelans are fighting a daily struggle to make a living. They lack access to education, health care and jobs.

Many have moved to neighbouring Colombia, but some have also gone to Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Panama and Peru. The Covid-19 pandemic has led many desperate refugees and migrants to consider returning to Venezuela. More than 70,000 Venezuelans have returned home through the Colombian borders.

The regional humanitarian response plan for 2020 calls for USD 1.41 billion for humanitarian efforts. So far, only 15 per cent of funding needs have been met.

Mourners at the funeral of five indigenous guards killed during an attack in Colombia in October 2019. Violence continues to afflict rural areas and indigenous people are particularly vulnerable. Photo: Luis Robayo/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Mourners at the funeral of five indigenous guards killed during an attack in Colombia in October 2019. Violence continues to afflict rural areas and indigenous people are particularly vulnerable. Photo: Luis Robayo/AFP/NTB Scanpix

Aerial view of a coca leaf plantation in Colombia. Despite the 2016 peace agreement, many farmers are still forced to grow coca by criminal organisations and armed groups. Photo: Mauricio Dueñas Castañeda/EFE/NTB Scanpix

Aerial view of a coca leaf plantation in Colombia. Despite the 2016 peace agreement, many farmers are still forced to grow coca by criminal organisations and armed groups. Photo: Mauricio Dueñas Castañeda/EFE/NTB Scanpix

Sabina Florez, 59, works in a school kitchen near the Venezuelan capital of Caracas. She and her family are totally dependent on communal soup kitchens to survive. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Sabina Florez, 59, works in a school kitchen near the Venezuelan capital of Caracas. She and her family are totally dependent on communal soup kitchens to survive. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Europe

In 2016, the EU reached an understanding with Turkey, whereby Turkey would prevent refugees from entering Greece and would accept refugees who were returned from there. In return, the EU would provide financial support to help the refugees in Turkey.

The understanding led to a sharp decline in the number of asylum seekers arriving in Greece. In total, there are almost four million refugees and asylum seekers in Turkey. Most of them come from Syria.

In March 2020, Turkey threatened to terminate the “agreement” and allowed a large number of asylum seekers to cross the border to Greece. It was a protest against the EU’s lack of support for Turkey’s military operations in Syria. Greek authorities tried to stop asylum seekers from entering Greece, and several were physically sent back across the border without having their asylum application processed, in violation of the Refugee Convention.

Refugees are living under unacceptable conditions

Greece faces major challenges in taking care of the 186,000 refugees and asylum seekers within its borders after the rest of Europe began to refuse to allow asylum seekers to travel to other countries.

In many places, humanitarian conditions are terrible.

The Moria camp in Lesbos houses 19,000 refugees and migrants – in a camp that was designed for 3,000 people. The hygiene conditions are very poor, and the camp is therefore especially prone to outbreaks of the coronavirus.

A child collects utensils from the garbage in the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos. The camp is severely overcrowded and hygiene conditions are poor. Photo: Florian Bachmeier/Imagebroker/NTB Scanpix

A child collects utensils from the garbage in the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos. The camp is severely overcrowded and hygiene conditions are poor. Photo: Florian Bachmeier/Imagebroker/NTB Scanpix

A boat containing 54 Afghan refugees arrives on the Greek island of Lesbos. In 2019, 60,000 refugees and migrants made their way across the Mediterranean to Greece. Photo: Angelos Tzortzinis/dpa/NTB Scanpix

A boat containing 54 Afghan refugees arrives on the Greek island of Lesbos. In 2019, 60,000 refugees and migrants made their way across the Mediterranean to Greece. Photo: Angelos Tzortzinis/dpa/NTB Scanpix

No agreement in the EU

EU countries have not been able to agree on a binding division of responsibilities and few countries have so far been willing to accept the asylum seekers currently in Greece. The United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) has urged European countries to accept asylum seekers from the camps, and in particular the 4,500 unaccompanied children who are now in Greece.

Eleven EU countries, with Germany at the forefront, have now stated their willingness to accept as asylum seekers 1,600 unaccompanied minors and other vulnerable people from camps in Greece.

Changing migration routes

In 2019, 60,000 refugees and migrants made their way across the Mediterranean to Greece. This is almost double the number compared to the previous year. In addition, 15,000 crossed the border from Turkey.

This stands in sharp contrast to the decline in arrivals to Spain and Italy. Only 11,000 managed to make it to Italy, which is less than ten per cent of the normal number in the period from 2014 to 2017. Migrants and refugees were frequently stopped in Libyan waters – and returned to Libya – by the Libyan Coast Guard, trained and equipped by Italy with EU support. This trend from 2019 has continued into the first five months of 2020.

In 2019, a total of 613,000 asylum seekers came to the 27 EU countries. That’s 64,000 more than the previous year. Syrians, Afghans and Venezuelans were the three largest groups of asylum seekers. Germany, France and Spain were the countries that received the most asylum seekers.