2019 will be another year of crises

At the start of 2018, 68.5 million people were displaced by war and violent conflict. There is little evidence to suggest that we will see this number decreasing in 2019.

A hope for 2019 is that old, relentless conflicts will be resolved. But political solutions require political will, like we witnessed this summer when longstanding enemies Ethiopia and Eritrea signed a peace agreement. This is good news for all countries in the Horn of Africa.

However, we are still facing numerous challenges: What will happen in Syria? Will the peace agreement in South Sudan hold? Can we get a peace agreement in Yemen? Will the Rohingya refugees be able to return to Myanmar?

Lack of money

One major problem is rich countries’ lack of will to stand up for the world’s vulnerable, displaced people. The great gap between humanitarian needs and funds made available by the international community continues to increase.

By the start of December 2018, only 57 per cent of the UN and its 2018 humanitarian partners’ emergency appeal was covered. According to the emergency appeal for 2019, 132 million people will need humanitarian aid in the coming year.

Humanitarian funding (orange) is not keeping up with the need (blue). Source: OCHA/Financial Tracking Service, dec 2018

Humanitarian funding (orange) is not keeping up with the need (blue). Source: OCHA/Financial Tracking Service, dec 2018

On 17 December, the UN General Assembly adopted a new global compact for refugees. The hope is that the countries will now act on the promises of better international responsibility sharing in practice. Rich countries that receive relatively few refugees must increase their support to countries that welcome high numbers of refugees. It is also important that more countries open up their doors to resettlement refugees. These are people who cannot be protected in their current location, and are resettled through the UN to other countries. In the first ten months of 2018, only 45,874 refugees were resettled to a third country. The UN estimates that 1.4 million people will need protection through the resettlement programme in 2019.

Today, 85 per cent of the world’s refugees are living in low- and middle-income countries. As humanitarian crises last longer and needs increase, aid is not sufficient. The innocent victims of conflicts, the civilians, always pay the highest price. They will also do so in 2019 unless we step up our efforts. For that to happen, we need courageous politicians with a will to act.

An ocean of humanitarian crises

From a global perspective, developments in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East are causes for concern, which they also will be in 2019. However, the situation of the Rohingya who fled from Myanmar, violence driving people through Central America to the United States, and the situation in Venezuela have again forced people in Southeast Asia and Latin America to become refugees.

Africa

The neglected continent

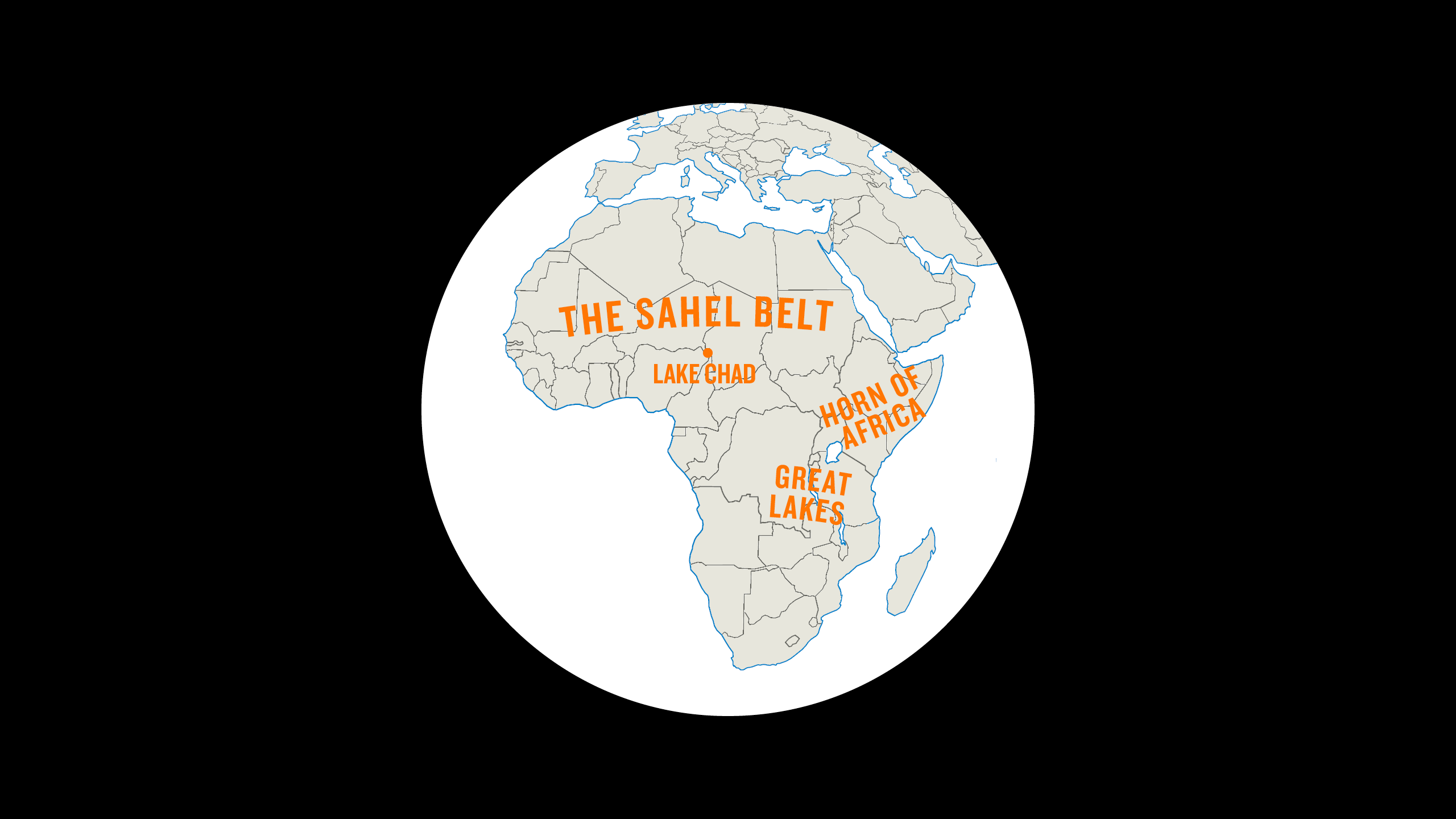

The number of displaced people in Africa has been on the rise since 2011 – from 13.3 million in 2011 to 22.4 million in 2017. Many countries have also repeatedly appeared on NRC’s annual list of the world’s ten most neglected crises, where the majority of countries are African.

Millions of people fleeing some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable states not only fuels enormous humanitarian crises, but also prevents development in regions such as the Great Lakes, the Horn of Africa and the Sahel.

The Sahel

The migration flow to Europe in 2015 drew attention to the situation in the Sahel region. The political focus on migration and terrorism promptly attracted money for anti-terrorist operations, as well as coast and border guards. But the vulnerable civilian population in the region’s conflict areas is yet to see stability. They are still suffering from violence and displacement.

In Mali, only 52 per cent of the funds needed to help people affected by conflict and violence has been received as we approach the end of 2018. Meanwhile, the security situation in the country has deteriorated sharply.

Dramatic ripple effects

The conflicts in Mali and in north-east Nigeria have major consequences for many countries in the Sahel region and around the Lake Chad Basin. The security situation in Mali deteriorated further in 2018 and violence has spread from the north to more central parts of the country. Many refugees are too scared to return home. Meanwhile, many fear that the conflict will become protracted and that it will grow worse in 2019.

Two sisters in a camp for internally displaced persons in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Photo: Hajer Naili/NRC

Two sisters in a camp for internally displaced persons in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Photo: Hajer Naili/NRC

The armed conflict in north-east Nigeria, which continues to affect every country in the Lake Chad region, has created a humanitarian crisis for a population that is also facing a number of challenges such as extreme poverty, climate change, chronic food shortages, the uprising of several armed insurgents, and organised crime.

There are no short-term solutions for the challenges in this part of the Sahel belt and the areas around the Lake Chad Basin, and people will continue to bear the brunt of violence in 2019. Humanitarian assistance must be prioritised to a much greater extent, and long-term assistance must have a clear focus.

Without international support, many countries in the Sahel will not be able to meet the UN sustainability goals, and thousands more will be forced to flee.

Critical in Cameroon

Cameroon plays an important role in this vulnerable region, both politically and in terms of humanitarian assistance, with its strategic location in the Sahel border region. The country houses more than 350,000 refugees from neighbouring Nigeria and CAR, while violence caused by the Islamist rebel group Boko Haram has forced 228,000 Cameroonians to the border areas to Nigeria. Cameroon’s stability is now increasingly threatened by its internal conflicts.

Meanwhile, the unrest in the English-speaking areas of south-west and north-west Cameroon has been on the rise after talks between government and opposition groups broke down in 2017. In the autumn of 2018, 437,000 Cameroonians were displaced in these areas, while 30,000 fled across the border to Nigeria and became refugees. There is a great risk that violence will surge in 2019.

The Central African Republic (CAR) is the world’s third worst humanitarian crisis, after Yemen and Syria, based on the proportion of people dependent on humanitarian aid. One in four Cameroonians have been forced to flee. Still, in November 2018, humanitarian organisations lacked over half of the funds needed to provide people with lifesaving assistance, while the peacekeeping force MINUSCA was underfinanced.

Without fresh funding, one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises will continue to wreak havoc in 2019.

Philomene is disabled and lives with six children in a camp for internally displaced persons in the Central African Republic. Photo: Hajer Naili/NRC

Philomene is disabled and lives with six children in a camp for internally displaced persons in the Central African Republic. Photo: Hajer Naili/NRC

Optimism in the Horn of Africa

When Eritrea and Ethiopia signed a peace agreement in July 2018, hope spread across the Horn of Africa, one of Africa’s most conflict-affected regions. Now, sanctions against Eritrea will be lifted, and the ripple effects may grow to be significant – thousands of families divided by the conflict have already been reunited. However, lifting travel restrictions between the two countries has also seen a rise in asylum seekers to Ethiopia in the autumn of 2018. But increased stability and hope of reform in Eritrea give us reason to hope the number of Eritreans embarking on the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean will decline in the future.

The accelerating democracy process in Ethiopia may also, in the long term, provide hope for solutions to the country’s own conflicts. It’s urgent. No other country in the world has seen higher internal displacement this year than Ethiopia, according to NRC’s Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre’s mid-year report.

In the autumn of 2018, violence and conflict led to hundreds of thousands of new displaced people. It is now very important that the international community step up their efforts to provide sufficient assistance. If the positive side effects of the peace agreement are not maintained, the political and humanitarian costs can be extremely high.

An uncertain peace in South Sudan

More than four million South Sudanese, one third of the population, have been forced to flee over the last five years. The peace agreement signed by President Salva Kiir, rebel leader Riek Machar and other armed opposition forces in September 2018 spurred hope, but many displaced people still fear that violence could explode again.

South Sudan enters 2019 with hope, but first and foremost with uncertainty.

Less to those who welcome many

In East Africa, support to humanitarian assistance in key host countries such as Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, has been severely cut in 2018. Wealthy countries, who have an increasingly restrictive refugee policy, provide some support to those countries that still receive a large number of displaced people. The East African countries house two million refugees, while the total number arriving Europe is decreasing.

Continued crisis in Somalia and DR Congo

Also in Somalia, one of Africa’s protracted humanitarian crises, reduced support for humanitarian assistance has led to cuts in basic help such as food, water, health and education. The support has been cut in spite of increased conflict levels and new tens of thousands displaced people in the autumn of 2018.

The Democratic Republic of Congo topped NRC’s list of the world’s ten most neglected crises in 2018. The country has never before seen more displaced people. The number of people without enough food to eat has also doubled from 7.9 million in 2017 to over 15 million in 2018.

The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize 2018 to Congolese gynaecologist Denis Mukwege will hopefully lead to an increased focus on the conflict’s invisible victims of sexual violence.

Europe

Fewer migrants and refugees

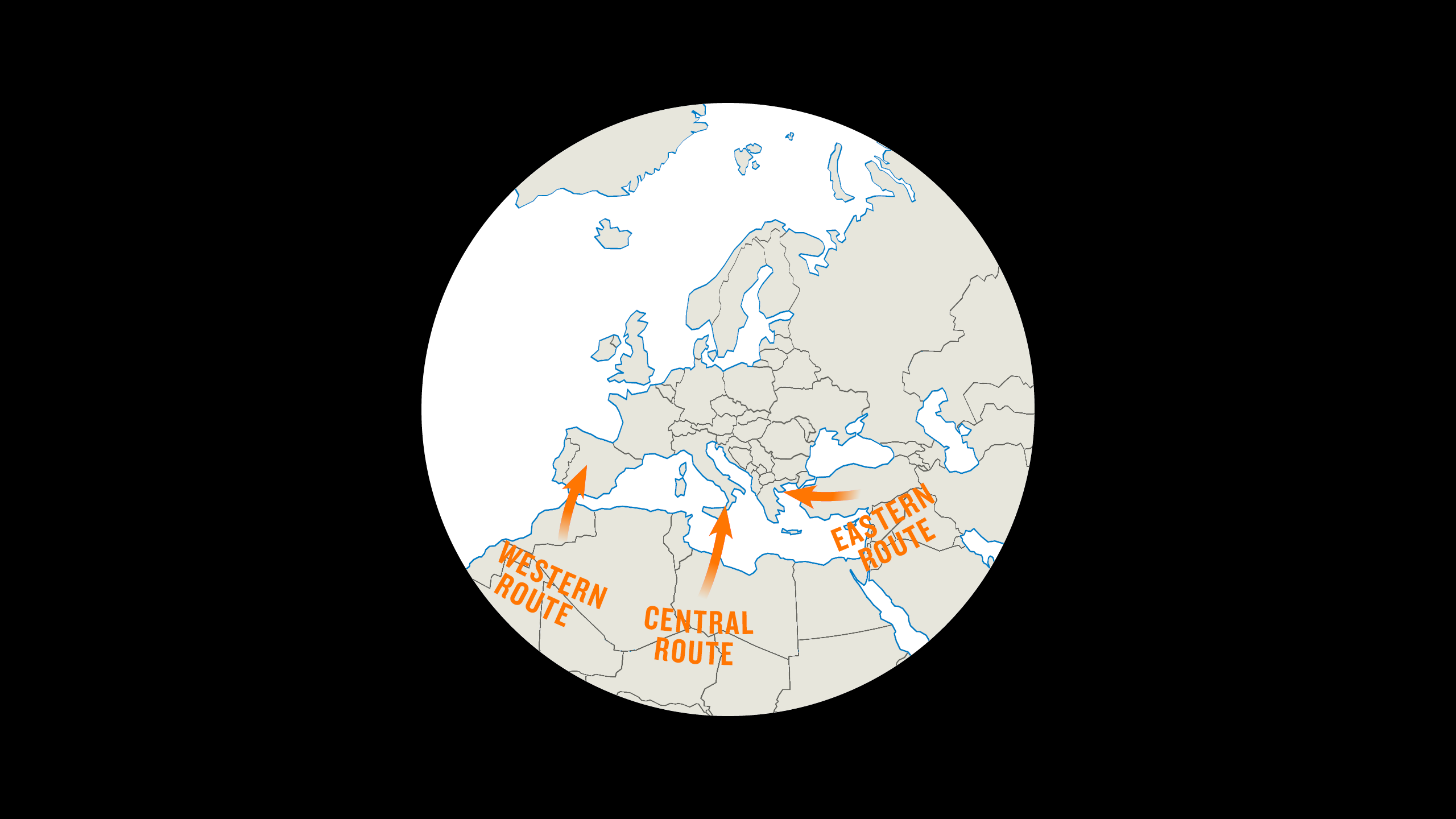

There have been far fewer refugees and migrants arriving Europe in 2018 compared to last year. The main reason for this is that it has become more difficult to get to Italy via the Mediterranean Sea route from Libya.

Italy is funding the Libyan coastguard, which now picks up most people trying to reach Italy and returns them to detention camps in Libya, where they are left in inhumane conditions. Italy has also refused boats with refugees and migrants to dock. In the first ten months of 2018, only 22,000 took the sea route to Italy, compared to 111,000 in 2017.

The western Mediterranean Sea route through Morocco to Spain is now the main route to Europe with 50,000 arrivals by October 2018, over twice as many as last year.

Ukraine

The conflict between government forces and separatists in eastern Ukraine has been ongoing since 2014. Here, 3.5 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance.

Displaced people lack shelter and other necessities of life, and prolonged displacement makes it particularly necessary to find lasting solutions. There have been no signs of an immediate solution, and in November, the situation deteriorated sharply when Russia took control of Ukrainian naval vessels in a strategic area by the Black Sea.

As winter is approaching, many are worried – what will happen next?

The Middle East

Continuing political unrest, war and mass displacement

Uncertain return to Syria

The conflict in Syria has led to the biggest refugee crisis of our time. Although the government took control of a number of areas in 2018, the lack of security and major destructions mean that the humanitarian crisis is far from over. More than six million people are still displaced inside the country. Despite a political agreement that prevented an escalation of violence in Idlib, people continue to live in uncertainty.

Some refugees have spontaneously returned to Syria, but there is a growing concern that worsening conditions for refugees residing in neighbouring countries will force more people to return home early to unsafe areas.

The support to neighbouring countries, which host millions of Syrian refugees, must continue in 2019, to prevent Syrians from having to return home before it is safe to do so.

Iraq in ruins after IS group

On 9 December 2017, the Iraqi Prime Minister declared that the war against the Islamic State group was over and won. A year later, however, 1.8 million people are still internally displaced in Iraq, while 8 million are in need of humanitarian assistance.

Although more than four million Iraqis have returned home, many of them live in the ruins left by IS. In cities like Mosul and Ramadi, there is an immediate need to rebuild houses, schools and hospitals to allow displaced people to return home safely. In some places like Sinjar, the reconstruction process has barely started. The city is in ruins, with no functioning schools or hospitals. More than 200,000 Yazidis are still displaced with no home to return to.

Awarding the Nobel Peace Prize for 2018 to the Yazidi woman, Nadia Murad, has helped to give the Yazidis a voice. It is also a contribution to the fight against the use of sexual violence as a weapon in war and conflict. It sheds lights on the need for victims to access justice across Iraq, and for perpetrators of violence to be held accountable for their actions.

National and local reconciliation efforts, supported by the international community, are also needed to help address community, ethno-religious, and tribal tensions that have been exacerbated by the conflict with IS. These are essential steps that must be undertaken to ensure Iraq’s path to stability and a recovery process in 2019.

2018: A disastrous year for Yemen

This year has been devastating for the people of Yemen. Over 22 million are in need of assistance, and thousands of civilians have been injured or killed. At the end of 2018, the population is continuing to suffer through one of the worst famines we have ever seen.

Violence, blockades of ports, the collapse of the labour market and an economy in freefall mean that millions of Yemenis are on the brink of hunger as the year comes to an end. The survival and security of millions of Yemenis now depend on the negotiations between the parties of the conflict, which took place in Sweden in December. A minimum outcome must be that all parties promise to abide by international law and refrain from war tactics that increase civilian suffering.

Asia

Afghanistan and Myanmar stand out

Civil war, drought and hunger in Afghanistan

The security situation has deteriorated in large parts of Afghanistan, and the parliamentary elections in October 2018 became one of the country’s bloodiest. In July, large areas were affected by drought, and in the period up to November 2018 the combination of conflict, drought and hunger forced 266,000 people to flee.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees are forced to return to the war-torn country from neighbouring countries. Seven in 10 of those returning become displaced again, according to an NRC report.

The Rohingya are too scared to return home

In June 2018, Myanmar and the UN signed a letter of intent on the return of around 700,000 Rohingya refugees in neighbouring Bangladesh. Its goal was to ensure a “voluntary, safe, dignified and sustainable” return for the refugees. According to the UN, the Rohingya are one of the world’s most persecuted minorities. Destroyed villages and a rhetoric of hate mean that many people of the Muslim minority are too scared to return home. Nevertheless, this was not the first time a return agreement was signed.

In November 2017, Myanmar and Bangladesh signed an agreement to start returning the Rohingya refugees. However, in October 2018, Bangladeshi authorities stated that the refugees refused to accept voluntary return because their villages were destroyed, and they were worried about what would happen to them if they went back.

Central America

Extreme violence forces thousands to flee

In Latin America, three crises are emerging, taking place in parts of Central America, Venezuela and Colombia. In Central America, organised crime, violence and poverty have for several years forced people to leave their home country. This is especially serious in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, also known as the Northern Triangle.

Although more people are seeking asylum in Mexico, Belize, Costa Rica and Panama, there are still many who continue north to the United States, a country that has sharply tightened its asylum policy. At the end of November 2018, US police clashed with migrants who attempted to cross the border. President Trump is trying to change the law so that migrants and asylum seekers cannot enter the country before they have received their asylum applications, while Mexico has asked the UN for help to prevent a humanitarian crisis. By December 2018, over 67,000 Hondurans who escaped from violence and poverty had returned from the United States and Mexico.

The problems in Central America are complex and will take time to solve. Of the world’s 50 most violent cities, 42 are in Latin America. The combination of weak state institutions, corruption, organised crime, extreme social inequality and violence is an explosive cocktail. There’s no quick fix here, and in 2019, the United States and Mexico will play key roles in dealing with these challenges.

Humanitarian crisis in Venezuela and a fragile peace in Colombia

Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis deteriorated in 2018. Thousands of people fled the country daily in 2018, often to neighbouring countries Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador and Peru. In November 2018, the government finally accepted humanitarian assistance from the UN.

Most of the people who leave Venezuela cross the border to neighbouring Colombia, a country that is going through a demanding peace process. When Iván Duque of the right-wing party, Centro Democratico, won the presidential election in June 2018, he aimed to change the peace agreement with FARC, which caused frustration among demobilised guerrilla soldiers. A lack of trust between the conflict parties has created a fragile peace. In the last six months of 2018, social leaders have been murdered and armed groups have displaced civilians as they try to take over former FARC-controlled areas.

Another negative trend is the large increase in coca production. Lack of security also means that many displaced people are worried about returning home. A peace agreement between the ELN group and a number of demobilised FARC soldiers is also yet to come. As the latter are leaving the demobilisation camps, their rivals are picking up arms. Although FARC leaders are adhering to the peace agreement, increasing dissatisfaction puts it under pressure.

It’s important that the peace agreement in Colombia and its intentions be respected in 2019. The situation in the country requires reconciliation, not polarisation.

As we enter 2019, displacement crises are still lining up. Emergency aid and political will to resolve conflicts are essential in order to relieve the suffering of people forced to flee all over the world.

Text over media